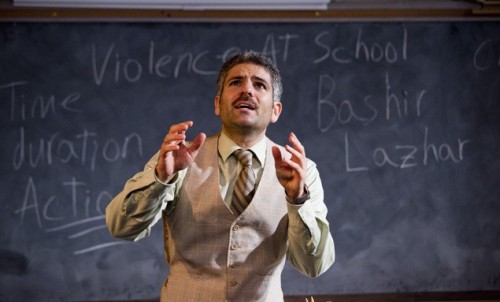

Bashir Lazhar at Barrington Stage

Juri Henley-Cohn as an Algerian Refugee in Montreal

By: Charles Giuliano - May 27, 2013

Bashir Lazhar

By Évelyne de la Chenelière

Translation by Morwyn Brebner

Directed by Shakina Nayfack

Juri Henley-Cohn as Bashir Lazhar

Scenic and Costume Design, Brett J. Banakis; Lighting Design, Robert Brown; Original Score and Sound Design, Anyhony Mattana; Dialect Coach, Stephen Gabis; Director of Production, Jeff Roudabush; Production Stage Manager, Paul Vella; Press, Charle Siedenburg

St. Germain Stage

Sydelle and Lee Blatt Performing Arts Center

Barrington Stage Company

Pittsfield Mass.

May 22 to June 8, 2013

Running time 80 minutes with no intermission

The set, designed by Brett J. Banakis, is a drab, generic class room of an elementary school in Montreal. There is a window with blinds through which light, designed by Robert Brown, conveys the time of day as well as aspects of radiance and hope. The staccato flashing of overhead lighting signifies terrorism in Algeria through a series of flashbacks in a one act play that conveys a variety of settings and circumstances.

With a daunting economy of means and a few props, like a desk that Bashir Lazar, as played by Juri Henley-Cohn, now and then turns around to switch from class room to the principal’s office, or the immigration board. It is a complex tale directed with deft legerdemain by Shakina Nayfack.

The blackboard serves as a kind of power point for the play. It is how Lazhar inserts key words, starting with the spelling of his name, that help us to navigate the complex terrain of the drama. The erasing of the blackboard at the end of the play is a metaphor for a man who has lost hope and dreams.

In a quixotic tilt with the daunting foes of ignorance, violence, suicide and terroism a wan triumph of the prevaling human spirit grasped from the jaws of defeat is the premise of a heart warming tale.

The thrust of the play is to convey an illusion of a meek, introspective, poetic, compellingly sincere, immigrant substitute teacher striving to teach, motivate and inspire a class of emotionally damaged children ranging in age from 11 to 13.

Mid term he has talked his way into the position having read the horrendous story of the teacher he replaces who hung herself in the classroom. Knowing that the principal would be hard pressed to replace the teacher he has falsified his qualifications. He states that he has permanent residence status which is not true. More significantly has never been in a classroom.

His wife was a teacher and he helped her to correct homework. Specimens of which he offers to the principal as examples of his work. They are his only falsified credentials. It is implied that under normal circumstances Lazhar would be a long shot for the job.

There is much to admire in the finely honed performance of Henley-Cohn who, having grown up in Connecticut of Polish heritage, has mastered an Algerian dialect. Under the guidance of Nayfack he negotiates many entrances, exits, shifts of mood and setting. In that regard the staging and acting are impeccable.

The production extracts all that is potentially available in this play, translated from the original French, by Évelyne de la Chenelière. My concerns are with the scope and agenda of the drama and development of Lazhar’s character and back story.

The play, which preceded the film Monsieur Lazhar, a 2012 Academy Award nominee for Best Foreign Film, is about suggestion and illusion. The film, which I saw as background to the play, fleshes out and fills in gaps that are implied on stage. The film is more literal and linear in telling the tale of this immigrant seeking refugee status and protection by the Canadian government.

As actors state repeatedly, with frustration and annoyance, comparing a play to a film is a matter of apples and oranges. But a conflation of media allows for an enriched sense of the intentionality that informs the conflicts in the telling of this story.

Even combining film and play, however, leaves lingering and unrealized questions about the character and his motivation. On fundamental levels I don’t understand this man, his emotions, or seemingly lack thereof, and understated, repressed responses to the horrors of living in Algeria. It is echoed in a classroom of deeply traumatized students. He has dealt with his own horrific loss of loved ones and leverages this as a resource to relate to and draw out the wounded students.

That would seem to be a win win but not a part of the daily curriculum.

As written the character tries too hard to be vulnerable, strong in uncanny ways, clever in his techniques of reaching the students, and a cog in the wheel of the immigration apparatus. In too many ways he just doesn’t feel real and believable. On stage he is alone and isolated while the film explores uneven success in relating to colleagues and reaching individual students.

Why Algeria?

We only have glimpses and bits of information about how his family perished through accident, a fire in their building, or was it the result of terrorism? This is more specific in the film. It is a crucial difference in establishing his status as a refugee. If the fire was an accident there is no threat to his safety if deported to Algeria.

Significantly, but almost in passing, we learn that he is of Islamic heritage but an intellectual and atheist. Just what does that mean in a fundamentalist, fanatical culture?

He ran a small café where people come and talk. There is an implication that it was a gathering place that encouraged the expression of offensive liberal dialogues. Islamic extremists targeted his family resulting in threats.

Lazhar, in flashbacks, reveals that he came to Montreal to find a job prior to being joined by his family. Despite threats his wife, a dedicated teacher who inspires his own approach, wanted to finish the school year. The play offers more details of their plan of how she and the children would escape the country.

The film and play have differing levels of success. In the film there is more depth to his relationships in the classroom which are nuanced, engaging and complex. The play confines itself to realizing only Alice who has beautifully expressed feelings in an essay dealing with the suicide of her teacher.

He is so moved by her maturity and eloquence that he presents it to the principle and asks to copy it to share with parents of the students. The intention is to create a dialogue about the trauma. In this initiative he has stepped outside the bounds of the curriculum. The school has assigned a psychologist to have weekly meetings with the class.

There is a forced agenda and the all too familiar trope of a sensitive, creative teacher at odds with a stifling and unimaginative lesson plan. We find this humble and deeply wounded immigrant bucking the system. It is, perhaps, what evoked a standing ovation from an audience that identified with his fragile, striving, but wounded persona.

Given the material this was a superb production of play that I had difficulty buying into.

One peeve. The original score of Anthony Mattana was simplistic, repetitive and annoying. It is within the genre of serial music and minimalism. The recorded music was played way too long before the opening of the play. It was getting under my skin. Prior to the first words it was turned off, and then resumed as the score of the play. With no variation it was used to convey emotional shifts only through volume control.

There was a welcome, witty change, when the style was applied to a variation on the national anthem “Oh Canada.” It was a comic take that set up the surreal, literally over the top, staging of Lazhar being examined by the immigration board. Here Nayfack has him sitting, then standing, on top of that ubiquitous desk. His precarious position accented the vulnerability of his actions.

It evoked and updated the macabre, frustrating nature of judicial bureaucracy so well conveyed by Kafka's novel “The Trial.”

While an interesting interlude, the most inventive of the production, it’s not really what this play is about. The essence of which escapes me.