High Line: Masterpiece NYC Urban Park

Building Upon Infrastructure In Creative Ways

By: Mark Favermann - May 25, 2010

Much lip-service has been given to redoing our nation's infrastructure, our society's basic physical structures like roads, bridges, sewers, etc. that keep our society functioning. Older pieces of the infrastructure like derelict docks, train rights of way and abandoned but visible structures are now being looked at as locations for potential community resources and renewal. One of the best examples of this is the High Line, now an urban park, located on the lower West Side of Manhattan in New York City.

Part of a massive public-private infrastructure project, the High Line was a 1930s project constructed to lift dangerous freight lines off of Manhattan's crowded, teaming streets. It was called the Westside Improvement Project.It lifted freight traffic 30 feet above the street, thus removing dangerous trains and sometimes cargoes away from Manhattan's largest and most dense industrial area. Trains stopped running on the line in 1980.

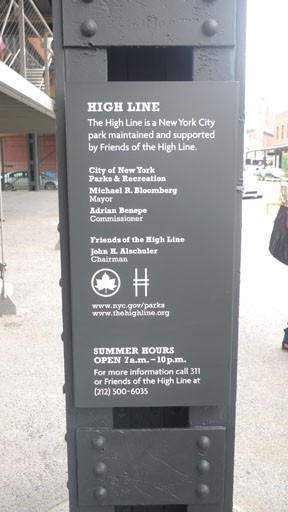

A community-based non-profit group, Friends of the High Line, formed in 1999 when the historic structure was under threat of demolition. Friends of the High Line worked in partnership with the City of New York to preserve and maintain the structure as an elevated public park. Receiving the City's support in 2002, the High Line south of 30th Street was donated to the City by the gigantic train and freight company CSX Transportation Inc. in 2005. Construction on the park began in 2006. The first section, from Gansvoort Street to 20th Street, opened in June 2009. Section 2, from 20th to 30th Streets is projected to be finished in 2011.

The High Line park plan was created by the design team of landscape architects James Corner Field Operations and architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The team created the High Line's public landscape. There was additional input and guidance from High Line supporters and interested community members. Diller Scofidio + Renfro certainly have had a great first decade of the 21st Century. They are the architects of Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art and the Lincoln Center 65th Street Project.

The Boston ICA was completed in December 2006. The Lincoln Center Project was begun in 2006 and will be completed in 2010. Addressing improvements to plazas and the grand entrance at Columbus Avenue, it will create a new pedestrian promenade designed to improve aesthetics and accessibility of the Lincoln Center campus.

The result of the design and community process was that the High Line is now a growing green ribbon for pedestrian promenades, escape from the urban grit and a touch of urban wild in a formally dense industrial and light manufacturing environment. This is an urban park that marries both the "urban" and the notion of "park" elegantly and refreshingly. High Line is an urban jewel.

In 2001-02, the Design Trust for Public Space provided a fellowship for architect Casey Jones to conduct research for "Reclaiming the High Line," a planning study jointly produced by the Design Trust and Friends of the High Line, setting out a planning framework for the High Line's preservation and reuse. After a 2002 study by the Friends of the High Line that demonstrated that the construction costs would be offset by new taxes generated from the public spaces and private enterprises that it would foster, the City of New York applied for appropriate Federal certification to reuse the space.

An open ideas competition was held during the first half of 2003, "Designing the High Line." It solicited proposals for the High Line's reuse. 720 teams from 36 countries entered. Many of the design entries were displayed at Grand Central Terminal. In 2004, Friends of the High Line and the City of New York conducted a process to select a design team for the High Line. The selected team were the eventual designers of the project. Along with James Corner and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, experts in horticulture, engineering, security, maintenance, public art, and other disciplines were chosen as part of the team.

In their 2004 competition entry, the design team showed a proposal that not only retained the sense of mystery and the reclaimed wilderness sense that made visual poetry of the deteriorating monumental structure. Thus, the new High Line Park would reflect the best qualities of the original High Line and its natural landscape.

With deference to the original character of the High Line structure, the designers considered its linear quality, its wild plantings of meadows, vines and flowers intermixed with railings, steel tracks and concrete. They conceived of something they refer to as "agri-tecture." This is a strategy of combining organic and building materials. This was build upon to create the new High Line.

Their design solution was developed in three parts. The first was to create a new paving system. This was built from concrete planks with open joints with tapered edges and seems. These details allow for free flow of water for irrigation and the intermingling of organic material with harder elements. The designers consider this less a pathway than a furrowed , textured landscape surface. The plantings accentuate this and the growing cycle of plants and flowers add to the visual dynamic of the space.

The second strategy was to slow down things to underscore a sense of being in another place, a place in contrast to the harder urban environment. Here, the design team wanted a feeling of time as less pressing. Long stairways, meandering pathways and seating niches encourage taking one's sweet time. The third approach was a strategy to consider dimension and scale to underscore the human quality of the space as opposed to the often big for big sake approach in other more intimidating environments.

The strategies work. The High Line has visually and qualitative integration of hard and soft, industrial and organic, natural and man-made. In entering the High Line, one feels that they are entering another type of environment, a special place with its own sense of time. The third strategy manifests itself in the feeling of personal connection through a clear sense of human scale. Though the structure, thus the park is large, the visitor feels comfortable, almost self-contained in this environmental experience. The details of the elegantly integrated minimalist sculptural benches, railings, fences and even drinking fountain underscore this.

The Friends of the High Line were interested in having something extraordinary created. In 2005, the design for the park was put on exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. Skeptics at the time said that it was impractical and could never be built as an urban park. The best ideas from that design have been refined and strengthened to result in the project that now New Yorkers and visitors can now enjoy.

The High Line is not the first great new urban park that has reclaimed space from a previously hard industrial environment. Pritzker Prize winning architect Bernard Tschumi created the Parc de la Villette in Paris at the outer edge of the 19th Arrondissement in 1984-87. This park is located on the previous site of the once huge Parisian abattoirs (slaughterhouses) and the national wholesale meat market. It was created as part of an urban redevelopment project. The slaughterhouses were built in 1867 and removed and relocated in 1974. To add interest to the environment, Parc de la Villette includes arrangements of structures and visual elements that Bernard Tschumi has dubbed follies.

In 2004, the City of Chicago completed its Millennium Park. The project was designed primarily by architect Frank Gehry. Located in the Chicago Loop, it has become a prominent civic center on the city's Lake Michigan lakefront. It covers a 25 acre section of northern Grant Park, an area previously occupied by Illinois Central railroad yards and vast parking lots. The park features major pieces of public art. Millennium Park has become a major tourist attraction for Chicago.

A third significant recent urban park is the City of Seattle's Olympia Park. This sculpture park opened January 2007. It too was built upon reclaimed derelict industrial land. Previously the site was was occupied by Unocal, the oil and gas corporation until the 1970s. Subsequently it became a contaminated brownfield designated parcel that needed much decontamination.

The City of Seattle eventually adopted the Seattle Art Museum proposal to transform the area into one of the only Downtown Seattle green spaces. Designed by Weiss/Manfredi Architects and Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture, Olympia Park is situated at the northern end of Seattle's seawall and at the southern end of Myrtle Edwards Park. Olympia Park is operated by the Seattle Art Museum.

It is a damn shame that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and due to its location, the City of Boston, lost the creative opportunity to have a new 21st Century landmark park like these other cities have. At every level, the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway is a sad effort. Located where the former elevated portion of U.S. Route 93 or Central Artery was and torn down for Boston's notoriously expensive "Big Dig", it is an uninspired, patched together, narrow but somehow bloated, uninteresting, underused green medium strip. But, that discussion is for another article at another time.

The High Line is a wonderful urban experience. It was designed with care and attention to detail. It is an organic, living and breathing ribbon of sociability and even tranquility in a dynamic, ever-changing context. It is at once fragile yet resilient and strong. It is seasonal while being permanent, cyclical while being timeless. The park will always be in a state of growth and change. A place that was designed so that it can be democratically shared, the High Line is a urban masterwork.