Laos

Part Two: Vang Vieng

By: Zeren Earls - May 21, 2010

Travelling south from Luang Prabang to Vang Vieng by bus, we stopped at two villages en route to meet members of the Khumu and Hmong tribes, two of the fifty ethnic minorities in Laos, which has a total population of 6 million. Driving along the Khan River, which was lined with rice fields, we passed stilted bamboo houses, banana trees, pigs, and chickens. Our driver honked around the bends as we made our way up a mountain road flanked at the top by smoking fields.

The Khumu people, related to the Khmer, are farmers; their major crop is mountain rice, as was evident from the surroundings. We entered the village on foot, noting a sign given by the government in recognition of the village’s no-crime record. People squatted around wood fires in front of their homes against the chill of the mountain air. Like the pied piper, we attracted all the village children with bags of candy in our hands. Congregating around us, they received the candy with happy squeals, piercing the calm in the air. People appeared happy despite the apparent poverty. We visited a 90-year-old village elder and learned about animist shaman ceremonies for driving away bad spirits and making offerings to appease them.

Descending a road flanked by charred ground and blackened hills, we passed by workmen laying cable for telephone lines. Passing store fronts and an occasional motorcycle, we paid a toll to drive onto a paved road. Knowing how low salaries were, we suspected corruption at the sight of expensive cars. The landscape of surrounding hills was shrouded in smog. Villages with bamboo homes, laundry stretched between poles, and even big tour buses all appeared in silhouette. At 4500 feet we reached Phou (Mount) Khoun, where we stopped for lunch.

The government has put an end to nomadic life. Now everyone lives in a village with electricity. We also visited a Hmong village. As soon as our bus pulled up, children and adults appeared at the doorsteps of their houses, which lined a hill. We walked up to visit them. A widow who lived with her mother, six children, and six grandchildren welcomed us to her two-room bamboo house. Despite the crowd living in this small space, the house looked neat and orderly. Everyone seemed to have a designated area, including the family dog, who slept in a corner.

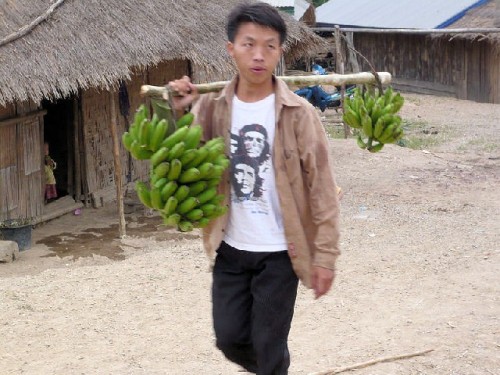

Originally from Mongolia, the Hmong are animist mountain people. Their language is similar to Tibetan. They have many children, and follow their own traditions and dress style. They are farmers, whose major crops are rice, corn, and chili peppers. Following the monsoon rains, the husband makes holes in the softened ground with a stick, and the wife then places seeds in these holes. In four months the rice is harvested using a sickle. There are two harvests each year; the rice field has to rotate every three years.

During the war with the Communists, the Hmong fought on the side of the king and the United States. After losing the war, they escaped to refugee camps in Thailand, and the US took on responsibility for them. The Hmong who stayed behind continued as terrorists, with support from those in the US. The largest US population of Hmong is in Minnesota. Since there is no longer anti-government activity by the Hmong, Laos has been open to tourists since 1999. Those who live in villages and have relatives in the US receive money from these relatives and are able to upgrade their living standards. The one overweight person I noted in the entire village was a woman who recently had returned from visiting relatives in the US.

Hmong make up 20% of the Laotian population. In Laos only those who work for the government receive benefits such as free health care. Though the country is a single-party republic, its economy is becoming increasingly capitalist. An Australian company operates a gold mine, and both Australia and Japan give scholarships to students to study abroad. How much of this opportunity trickles down to minority populations is hard to know. The candy we distributed to both adults and children seemed to suffice for now. They waved goodbye to us with big smiles.

Continuing on a mountain road, we reached Vang Vieng, our overnight rest stop on the way to Vientiane. Vang Vieng is nestled in mountains, and its scenic surroundings are renowned for their topography. Trekking attracts backpacking crowds, who sleep in places charging as little as $4 a night. Even restaurants offer reclining chairs as rest stops. There is also drug activity here; trading in drugs is illegal, and anyone caught with more than 500 grams of heroin faces a penalty of a very long jail term or even execution.

Descending from our bus, which was too big for the narrow path, we made our way to the Thavonsouk Resort Hotel on the Nam Song River. The staff met us with a welcome cocktail of refreshing lemon tea. Our rooms, with porches bursting with tropical shrubs and flowers, faced the river and the silhouetted mountains beyond. For dinner we enjoyed pumpkin soup, ginger chicken, tilapia, and stir-fried vegetables, accompanied by a big mound of rice. A fresh fruit platter with a variety of melons and pineapple completed our meal. After dinner we were entertained by the hotel owner, who sang English songs from the 60s to guitar accompaniment and included a few Elvis songs for flair. The stopover in Vang Vieng was a perfect interlude to our long journey to Vientiane.

In the morning we were back on the mountain road with spectacular scenery. We passed by people cooking breakfast along the roadside. Students on bicycles — boys in white shirts with dark pants and short hair, and girls in white shirts and dark skirts — rode to school. We stopped to visit an organic farm. The founder had received his university education in Sophia, Bulgaria and later joined the pro-Communist organization known as the Pathet Lao to free the country of colonial powers. He had worked for the government in forestry; he then started the farm with two acres of land in 1996, gradually increasing it to five and then to twenty acres.

Dedicated to teaching environmentally friendly ways, the farm attracts international volunteers through its website to live and work there in exchange for accommodation. We visited an adobe house built by young people from Israel, and watched goats being milked and fed by volunteers from Singapore. Having started with four goats imported from the French Alps, the farm now boasts twenty goats, which provide milk for babies in addition to cheese. There are no dairy products in the traditional Laotian diet; such dairy products as can be found are generally imported from Thailand.

Organic produce is less expensive on this farm, as vegetables with holes in the leaves do not look as pretty as those sprayed with chemicals. We walked among mulberry trees, citronella plants, lemon grass, and hibiscus. We were introduced to jackfruit, which tastes like potato and can weigh up to 30 pounds; it is eaten chopped or mashed. We enjoyed mulberry tea made by boiling the leaves over a wood fire and chopping the upper layer for high-quality and the stem part for low-quality tea. In the final stage the leaves are tossed by hand to bring out the aromatic flavor, dried, and packaged. We sampled sun-dried banana chips and mulberry leaf tempura, which were both delicious. I purchased a bag of mulberry tea, in addition to a scarf from silk produced on the farm. The proceeds from purchases go to support an English school for the villagers, who come to the farm to learn “the way of the future,” as internet technology spreads throughout Laos.

As we continued on our way to Vientiane, we learned that each group of twenty houses comprises a village. Every village has a chief, who makes sure people follow government regulations, such as displaying the Communist hammer-and-sickle flag in front of every house during festivals and voting every five years in parliamentary elections. Election Day is a holiday; people have to travel to their home towns to vote. All members of parliament belong to the Lao Revolutionary Party. They elect the Prime Minister and the President, who becomes the head of the Party.

We passed by rubber trees given by China. Rubber is exported to China and bought back as tires, rubber bands, and other finished goods. There is very little industry in Laos. Its only exports are agriculture, handicrafts, and electricity; even sugar is imported. The government owns the beer and cigarette industries. The main industry is tourism, with tax revenue generated by hotels. Most mining companies — copper, silver, and gold — are operated by the Chinese. Bridges are being built across the Mekong for easier and faster transportation to neighboring countries. Cars and motorbikes are subject to 50% import duty and therefore very expensive.

At one point our bus began leaking oil. The driver, who seemed used to solving problems on the spot, wrapped up the leak with rubber bands, and we continued on our way. Farm life gave way to city life. We drove onto a paved road lined with shops. Bicycle and motorcycle tires wrapped in colorful foil hung from shop rafters like ornaments. Goods stacked outside of stores ranged from brooms, baskets, and flower pots to soft drinks and stupas for burial grounds. Modest single-story cement homes with shrines alternated with wooden ones with typical Lao roofs. As traffic increased, so did small roadside restaurants with pastel-colored plastic chairs and vinyl covered tables catering to weary travelers.

Approaching Vientiane, European-style homes, clothing stores with mannequins, ornate temples, monks in saffron robes, tuk-tuks, beer ads, signs for banks and a dental clinic, and flags on official buildings signaled our much-anticipated arrival in the capital city.