Harold Pinter's No Man's Land at ART

Against Interpretation: It is what it is more or less

By: Charles Giuliano - May 17, 2007

No Man's Land, by Harold Pinter (1975). Directed by Davis Wheeler. Cast: Hirst, Paul Benedict, Spooner, Max Wright, Foster, Henry David Clarke, Briggs, Lewis D. Wheeler. Scenic design: J. Michael Griggs. Costume Design: David Reynoso. Lighting Design: Kenneth Helvig. Sound Design: David Remedios. Stage Manager: Amy James. Voice and speech coach: Carey Dawson. Dramaturg: Miriam Weisfeld. American Repertory Theatre, Cambridge, Mass. May 12 to June 10.

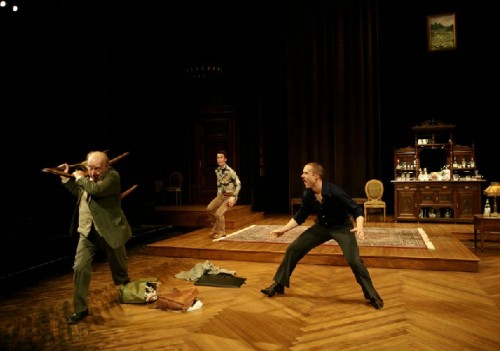

After a season of post modern, deconstruction it was a surprise to arrive at the American Repertory Theatre and find the kind of elegant, well crafted, traditional set (an upscale, spacious London apartment in 1975) that one is more likely to encounter on the other side of the Charles River at the Huntington Theatre. For once there were no glimpses into the wings or props set in a black box. What did this portend for the evening which lay ahead? Were we to be offered a straight ahead evening of theatre rather than a radical, avant-garde reworking of Racine's "Britannicus" (with Nero as a petulant rock star) or a new twist on "Oliver Twist" by Dickens. But have no fear. There was no need for an overhaul. This was, after all, "No Man's Land" by Harold Pinter which is to say, such a ponderous, confounding, treacherous and silver tongued, twister and turner that it requires no avant-garde tinkering. Quite rightly, the David Wheeler direction of Pinter's complex and brilliant play is straight no chaser. Served neat.

Which is, in fact, a more than apt analogy as the drama revolves around Hirst (Paul Benedict) a legendary author tied up in the Gordian knot of fame and memory which has rendered him dottering and unproductive and a bar rat, ersatz poet, Spooner, (Max Wright) whom he has dragged home from a pub for a nightcap. And another, and another, and another until Hirst literally falls down drunk and drags himself along the floor to a bedroom. In this play the two main characters, drink, and drink, and then drink some more. Never on stage has one seen more of the malt consumed in a single evening.

So why would one care for such terminal alcoholics? Drunks are readily available in any bar of one's choice. Why spend top dollar for an evening of boozy wisdom and eloquence. In vino veritas. Perhaps. But also lies, delusions, deceptions, melancholy, memory, anger, petulance and bathos. Did I leave anything out? And yet how much great art and literature has been laced with booze? How many great literary geniuses puked and pissed themselves to sodden sleep? Caught up in "The Touch of the Poet."

The apparent mistake of attending a Pinter play is to search for meaning or resolution. His work defines the notion of the absurd or stands against interpretation. This play much recalled the earlier ART production of "No Exit" by Sartre. But it was less stridently obvious as an exposition of theory and philosophy. Clearly Sartre may be the more profound thinker but Pinter is primarily a greater artist. There are many obvious parallels. In this case Hell as an upscale British apartment from which there is No Exit. Spooner, at the beginning of the second act, for example, asks Briggs (Lewis D. Wheeler) one of two handsome young thugs who are well paid retainers of the besotted Hirst, why he had been locked in the drawing room over night? Spooner, now sensing foul play as the situation grows ever more dark and ominous, tries to slip away to a fabricated, urgent, appointment. But Briggs sees through it and bars the door. Once in this incubator of agita there is no way out.

Cleverly, the resourceful Spooner, with a very British gift for gab despite his scruffy persona will launch into a long plea to Hirst to keep him on as a secretary. He gets the picture and aspires to the easy and cushy job of Briggs and the other guardian, Foster, (Henry David Clarke). Pinter likes the Aristotelian devise of reversal. The evening started with a long soliloquy by Spooner to which Hirst has little response. Then Hirst will launch into a screed with Spooner silenced. Now, for the last time, Spooner makes the greatest job application since Machiavelli's "The Prince." After listening with apathy and ennui Hirst responds to the crestfallen Spooner 'Let's change the subject, for the last time."

Ah, there's the hitch. "For the last time." Which means that absolutely anything deemed to be or have been the subject, Winter, for example, will never more change. If the topic, changed, for the last time, was Winter, then, it follows there will be no Spring. It will remain forever Winter. But, Hirst, interjects, "I hear birds. I never heard them before." So Hirst longs for Spring now, when locked into Winter, in a trope of his own devising, he has damned himself to have no Spring. Is this "Faust" or "The Man Without a Country?" But it is the human detritus Spooner who cuts to the chase offering that the four characters are now in a state of "No Man's Land." Curtain. Applause. What the heck.

Yes, The Play's the Thing. And stop making sense. Why not. Who needs resolution, insight and happy endings? Like those TV cop shows where the most complex crime is solved and wrapped up with a kicker all in an hour minus the ads. Not so for Pinter. He never sends you home whistling that happy tune. More likely, were I not accompanied by my attentive wife, to be truly Pinteresque, I would have headed for Hampstead Heath for a smarmy adventure ending an evening till last call with pints and shots at Jack Straw's Castle while watching a round of cricket on the telly.

No, art does not have to make sense. If it did perhaps it would not be art. Or not very good art. Perhaps it would be agit prop or illustration. Art does not have to teach us a good lesson. I got beatings enough from my Dad, thank you very much. I need no more floggings in the theatre or museum. I can get along quite well on my own. Which is why I rather like Pinter. He just tosses us in there. We get drawn into the flow of the language, the absurdity of the situations, the reversals, characters becoming each other. The sheer brilliance of the performances, which is the case here. Isn't that enough? Why would you want any more? Just let it be. Give it a rest. Take the licking if you have to. Try to find meaning and happiness somewhere else. Ultimately, an artist owes us nothing. Life is a Tempest. With time we are shipwrecked by Neptune, and there is no Penelope waiting for us when we wash up on the beach. Pinter's vision is dark and horrific but also well crafted and full of grace. But no redemption. There are no answers and here not even any questions. It just is.