War and Discontent at the Museum of Fine Arts

Carnage as Artistic Metaphor

By: Charles Giuliano - May 15, 2007

It is more than four years since President George W. Bush landed in a two man fighter plane on the deck of a carrier, strode to the microphone wearing an Air Force flight suit, (he had been a weekend warrior pilot, mostly no show, during the Vietnam War) and under a giant banner before the mustered out crew declared "Mission Accomplished." This past week Prince Harry, son of Queen Elizabeth 11 who was in the U.S. for the anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia and feted at the White House, joined his combat regiment in Iraq. In response to fears that his group will be targeted by insurgent terrorists, his comrades in arms are wearing T shirts with targets over their hearts that proclaim "I'm Harry." It is a poignant and powerful symbol of British grit and patriotism where sons of the Royal family take up arms while few if any sons of America's political, social and corporate elite are serving their nation.

Yet again this is a war fought by the urban and ethnic poor of a professional military and hard pressed National Guard. In many ways, this is a quiet and understated war. Because it doesn't involve the draft there is no mood of protest on college campuses and individuals making tough decisions to take refuge in nearby Canada. Although now pervasively unpopular, with the lowest historic approval rating of a President during a period of War, there has been relatively little agit-prop from the ranks of traditionally concerned artists. This in contrast to the plethora of anti war art, posters, and banners during the height of the Vietnam era. The nation is oddly quiet and benign as it faces the daily body count with relatively low American casualties, now past 3,000 but a fraction of other wars of similar duration. Reports of Iraqi deaths at the hands of Americans and through Civil War range as high as more than 600,000. That disproportion between U.S. and "enemy" deaths recalls the Vietnam "Conflict" which ultimately we lost.

With no ready timetable for victory or withdrawal, despite a "Surge" there seems to be no end or possible resolution to the quagmire about which the American people and politicians seem oddly apathetic other than a generic disdain for the ineptitude and platitudes of the President who just blusters, bumbles and blunders along toward the end of the least distinguished Presidency of the Post World War Two era. Compared to W., Eisenhower and Ford, or even Bush One, were monumental in their accomplishments.

So the current exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts "War and Discontent," curated by Cheryl Brutvan, through August 5, is both welcome, compelling, often intriguing, and curious. Very little of the work on view is recent. Brutvan has taken the risky approach of combining historic materials from the MFA collection including works by Goya, Manet, and Picasso and pairing them with art of the Vietnam era and a few recent examples of high art culled from a select A list of well established contemporary masters.

Brutvan and the MFA deserve much praise for even considering this show. It takes the kind of position on a hot button issue that the museum has not been known for. In the past decade plus the MFA has featured populist, feel good shows but that is not the case here. There is much in this exhibition to think about and be moved by. Indeed, I have found the experience lingering and haunting on many levels. It's good to have that kind of powerful experience but also sad and tragic that real life circumstances drive this aesthetic decision and the work that it embraces. There are always mixed feelings when approaching well crafted works of art with war and holocaust as a theme. Recently, Astrid and I viewed "Downfall" a rather long, two and a half hour film brilliantly starring Bruno Ganz as Adolph Hitler and his entourage in the last days of the Bunker in Berlin. The film was riveting and the performance of Ganz staggering in his ability to bring out all the range and nuances of the historical Hitler. Now, more than a week later, the film lingers and disturbs. There is a paradox of having experienced a phenomenal performance as well as the collateral damage of being haunted by it.

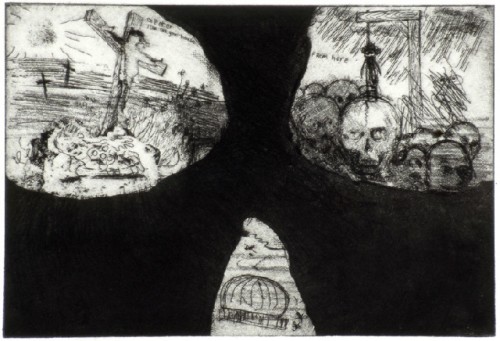

In a similar manner, this exhibition invades and disturbs me after a couple of visits over the past weeks. It is always gripping to view a selection from the "Disasters of War" by Francisco Goya, (1746-1828) inspired by the 1808 invasion of Spain by Napoleon's troops but published long after his death in 1863. They are paired here with a less compelling series of prints inspired by Goya's vintage images by the Brothers Chapman, British artists more noted for their surreal, erotic, horrific figurative sculptures.

Also from the MFA collection is the masterpiece "Execution of the Emperor Maximilian," 1867, by Edouard Manet. It is the most sketchy of the several works that were inspired by the execution of the French puppet in Mexico after Napoleon 111 withdrew forces needed to fight the Franco Prussian War which ended in disaster for France. The Manet painting was inspired by Goya's "Executions of the Third of May, 1808." It has been some time since we last saw the Manet hanging at the MFA as it is often on tour. We paused to absorb its brilliant, brushy, sketchy passages. Observing how he overpainted French military caps and transformed them into the sweeping rhythm of Mexican sombreros.

Less exciting was again viewing "Rape of the Sabine Women," 1963, which was the first Picasso painting purchased for the MFA, by former director, Perry T. Rathbone and his sidekick, Hans Swarzenski, during a visit to the artist's studio. It was late in the artist's career (1881-1973) when he was knocking off Picasso's. Particularly for rich tourists granted private audiences. With its dim, unfelt echoes of the genuine anguish of "Guernica" this painting has never been more than a colorful cartoon from the artist's enervating late period. The museum later bought a couple of more expensive, earlier, better, but not great, works by Picasso who is underrepresented in a museum with a global reputation in areas other than modern and contemporary art.

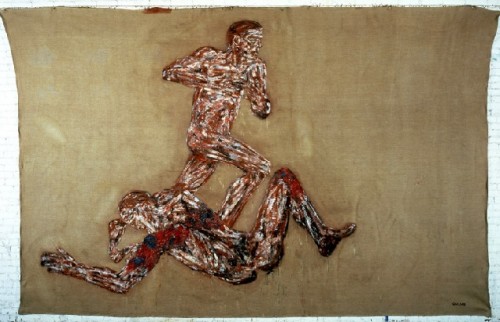

With those historic markers the curator has filled out the galleries. There are two riveting works by one of the greatest figurative/ protest painters of the Vietnam era, Leon Golub. He is represented here by the raw, burning flesh "Napalm" vividly depicted in an expressionist manner on unstretched, unprimed, linen, and the horrors of "Interrogation 1." Golub's 1980-81 painting is a grim precursor of what happened more recently at Abu Ghraib.

Conceptual artist Chris Burden has long tinkered with metaphors meant to quantify the unfathomable depth of weapons of mass destruction. In past works he suspended models from fish line to signify all of America's nuclear submarines. As a response to the lists of names of American dead in May Lin's Vietnam Memorial Burden created folding bronze screens engraved with the endless names of Vietnam's victims of war. Here he playfully deconstructs a naval battle vessel into an ersatz sailing ship. His drawings and model are all the more humorous, and grim for their duality between the plausible and not. Many of his constructions just might work but always have that catchy and thought provoking aspect of "but if." The work is both fun and playful and also horrific in its depth of implications with the bottom line that war is definitely not about fun and games although it may seem that way to hawks and war mongers with their John Wayne fantasies. Recall for example Robert Duvall's character landing on the beach of a bombed village stating that "Charlie don't surf" and "I love the smell of napalm in the morning" from the Coppola classic "Apocalypse Now." In this instance the Duvall helicopter commander is a boy/ man playing war games with real bullets. Burden's work often evokes a similar response.

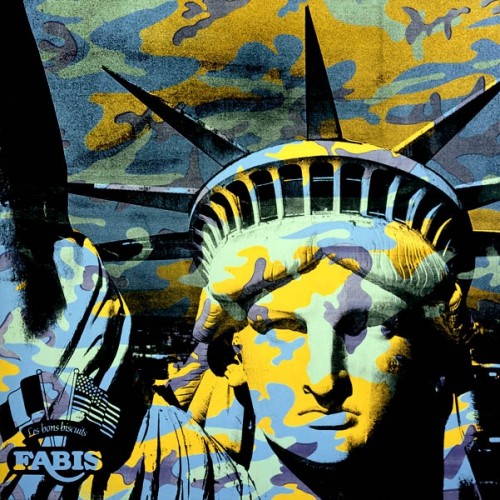

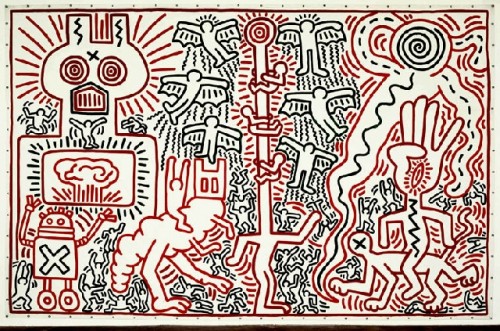

There are works in the show that make more sense for their iconic, celebrity status than providing a contribution to the theme and understanding of the exhibition. Given the choice curators often find a way to include Andy Warhol, relevant or not, here represented by a camouflaged Statue of Liberty as a metaphor of American at war, well, ok, but the grommeted work by the late graffiti artist, Keith Haring, is more of a stretch, or unstretched in this case. The more so because it is displayed outside the gallery in the corridor that leads to the exhibition. The casual observer might conclude that it is a catchy banner meant to accent the gift shop and upscale café. The big, ponderous, Robert Morris work in which the frame is a dark relief of tangled corpses, the body county of war, is well, big, ponderous, and a Robert Morris. There are those who continue to think of him as an important artist but that is more was than is. This piece doesn't really do much for the show. Ditto for a vague double depiction of bombers in a painting "Approach" (1989) by the enervating Richard Bosman.

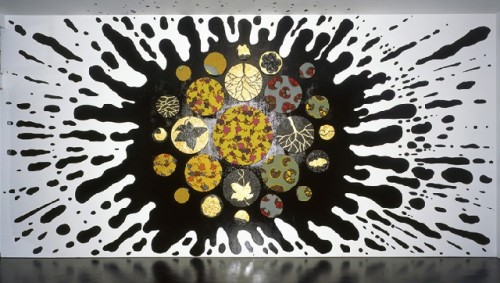

While there was an enormous range of work to select from Brutvan is not entirely judicious in her choices which seem clipped from Art Forum and Art in America coverage of this topic. Like the sprawling horizontal painting "Black Gold 11" by the African/British now Carribean based art world celebrity Yinka Shonibare. The conventional wisdom among curators is that pieces by the edgy Shonibare spice up a show. There are de rigueur examples by Shonibare in the lingering hodge podge at Mass MoCA on the theme of history or something like that. The usual approach among curators at top level museums appears to come up with some loosey goosey theme and then pepper it with art stars. Here, while tempting us with a provocative topic, Brutvan mostly follows the conventional wisdom.

Where curators make their bones is in offering us something fresh and provocative. Here Brutvan pulls it off by offering strong video selections. The video loops by Boston based artist Suara Welitoff presented a pop, Candy colored montage of the fighter planes of the Great Generation. She reached back for vintage war imagery but gives it a zingy update that is both sicky sweet looking in its pink, catchy, feminine colors and also head thumping when we realize that the mission of these planes is to decimate Axis cities including the fire bombing of Dresden.

The most memorable aspect of this project is the large, carpeted gallery given over to the video projection by the British artist Phil Collins "They Shoot Horses Don't They?" The title is a reference to the Jane Fonda film about the exhausting dance marathons of the Depression era when the last couple still shuffling about won some kind of meager prize. Here the dance marathoners are Palestinian teenagers who dance till they drop to a disco beat. On a Saturday afternoon when we visited there were several adorable girls dancing along with the video duplicating it step for step. They were so absorbed in their workout they were mostly oblivious to being observed and hardly at all aware that they were in an exhibition about war.

Ultimately, although it is not always a smooth trip, give Brutvan credit for taking us on a trajectory that starts with Goya and ends with Phil Collins. A lot happens in between. But while the kids dance to the Intifada Two Step half way round the globe innocent people are getting gunned down by good guys and evil doers. This exhibition makes us wonder which side God is on.