Henry Moore Sculpture Centre

900 Works at Art Gallery of Ontario

By: Charles Giuliano - May 13, 2019

In 1971, Henry Moore (1898-1986) began to donate works to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Canada. The initial phase occurred over the next three years. The Henry Moore Sculpture Center opened in 1974 and gifts continued through the Henry Moore Foundation.

Today the AGO owns 900 works including large plasters for bronzes, maquettes, drawings and related materials. The 1,200 square foot gallery and its ancillary displays comprise the largest public collection of the artist's work. Simply put, it is one of the most magnificent experiences of 20th century sculpture on a global level. It is not irreverent to state that it compares to La Grande Allée of "Slaves" for the abandoned Julius II tomb in the Accademia in Florence that culminates with Michelangelo’s monumental "David."

The scale of the Moore sculptures, with their many variations of the figure, are less monumental and more humanistic but no less agonizing in their uniquely emotional intensity. In the "Slaves," most of which are unfinished save for two in the Louvre, the Renaissance master in the maniera of neo Platonism, liberated the soul of the figures bound by their blocks of stone. Eschewing drawings and studies he found the forms by direct encounters with the stone.

That represents an aspect of abstraction that catapults across centuries to the manner of the great British sculptor. Initially, Moore, the son of a coal miner, also carved marble and wood. There were early years of struggle and poverty. Drawings in subways at night, London bomb shelters during the Battle of Britain, gained him global recognition. One of these precious drawings was callously sold by the Berkshire Museum to amass its pot of gold.

After the war. Moore received ever increasing commissions. He abandoned the labor intensive subtractive process of carving. Moore evolved to working with clay and plaster to create editions, usually six to eight, in bronze using the lost wax technique. In equivalence with the direct approach of Michelangelo he developed monumental works through sketching in clay and plaster. From there he worked out details with maquettes, then half scale, and eventually full size works in plaster which were sent to foundries. Molds are made from the plasters which remain intact.

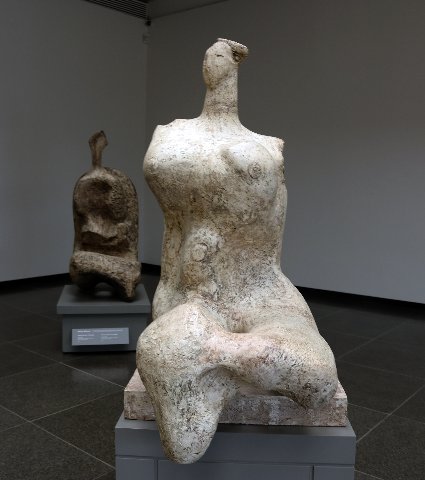

Plasters displayed at AGO were not finished works but rather a byproduct of creating bronzes. The plasters are fragile and somewhat ephemeral. Sculptors working with additive process aspire to cast in bronze. Few, however, can afford to. It is not uncommon that the version in bronze occurs long after the initial creations in clay and plaster.

When the Frech artist Edgar Degas died it was discovered that his studio was filled with small wax figures and horses. During his lifetime he was known for a single bronze "Little Dancer Aged Fourteen." Today we know of him as a sculptor as well as painter and graphic artist. It was a decision of the estate to cast the fragile and disintegrating sketches as a way of preserving them.

When Moore donated these working plasters to the AGO it solved several problems. In his mid 70s, he was concerned with issues of legacy. He was wealthy and paying some million pounds a year in taxes. There were concerns about severe British death taxes. Forming the Henry Moore Foundation was a way of solving financial issues and keeping the work intact. While works in bronze are durable those in plaster are not. For all of those reasons the large donation to AGO makes sense. He had received a commission for "Three Way Piece No. 2 (The Archer)" for Toronto's City Hall Plaza in 1964. So there was a connection to the city.

Despite achieving great wealth and fame Moore lived modestly. In July 1929, he married Irina Radetsky, a painting student at the Royal College. She was born in Kiev in 1907 to Ukrainian–Polish parents. After several miscarriages they had a daughter Mary (born 1946) named for the artist’s mother who was by then deceased.

During the war, their house was hit and they moved from London to a farmhouse called Hoglands in the hamlet of Perry Green near Much Hadham, Hertfordshire. Today it houses the foundation and maintains 70 acres as a sculpture park which, along with the home and studios, are open to the public.

In addition to the plasters the AGO was gifted a bronze work “Large Two Forms” which, since 1974, was sited at the corner of Dundas and McCaul Streets on the edge of the AGO. It has been relocated to a new home in Grange Park, the expanse of grass and trees on the gallery’s south side, as part of an $11 million makeover to add playgrounds, trees, bigger expanses of greenspace and a water feature.

Approaching the AGO it is surprisingly landlocked surrounded by Toronto’s Chinatown and the older, less upscale part of town. Given a confining footprint, the addition by Frank Gehry, a long narrow, curved, atrium like wraparound is among the least impressive of the architect’s projects. It entails a large and somewhat chaotic lobby with a large book store. A visitor is confused and disoriented regarding how to enter and navigate the collection.

At the end of Gehry’s long, vaulted atrium which is more a conceit than pragmatic contribution, one almost stumbles upon the Moore gallery. It remains as I recall from a visit some years ago. Knowing that it was there I made the effort to find it. The Gehry design did nothing to navigate one to this sublime experience. The space, while refreshed and beautifully illuminated, is unmodified. The ceiling patterns of exposed structures seems, well, so ‘70s brutalist.

By the time you end up in the space, having catapulted about through the chaotic array of galleries, one suffers a bit from paradigmatic museum fatigue. It helped that we paused for afternoon tea in the Gehry atrium to catch our breath before the final ascent for the summit of aesthetic experience.

A deep breath and whiff of oxygen was required fully to absorb the magnificence of the enticing treasure trove of Moore’s plasters.

Encountering a range of approaches in degrees of abstraction to reclining female figures was like spending time with old friends. These pieces were from the 1950s and 1960s but the series was initiated by a visit to the Louvre in the 1930s. There he was inspired by ancient Mexican Chac Mool figures, such as one from Chichen Itza.

While there are a number of single figures, generally reclining, the sculptor was also noted for evolving the human form into separated masses. Another signature element is the accent of voids. Initially, that came from views through arranged arms, but in dialogue with friend and fellow sculptor, Barbara Hepworth, these negative spaces became a signature aspect of their shared visual vocabulary.

Most compelling was the experience of the manner in which Moore scratched and scored some surfaces. When, as a student, he initiated this rustication he was reprimanded by an instructor who insisted on polished surfaces. This art brute approach makes Moore more akin to School of Paris and Giacometti (born Swiss). For a time they shared an interest in surrealism.

Moore traveled, including the U.S. and frequently to Paris. A study beyond the scope of this report is his place in international modernism. In addition to knowing more about what influenced him there is the enormous topic of his impact on other sculptors including Anthony Caro, Reginald Butler, Kenneth Armitage, Sir Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi and Richard Wentworth.

While the surface of the plasters is the revelation of the works at the AGO it is generally less evident in the resultant bronzes. Primarily, Moore favored gold colored, shiny bronzes and to some extent patinated oxidized green. He appeared to be more concerned with form than finish.

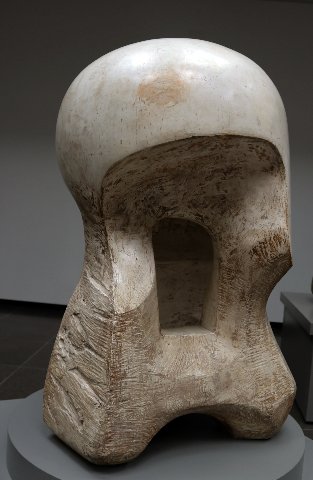

The thrill of this visit was a study for “Nuclear Energy.” It was unveiled on the campus of the University of Chicago in December 1967, 25 years to the minute after the team of physicists led by Enrico Fermi achieved the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Even at a lesser scale than the 12’ sculpture the impact was palpable.

The smooth domed top of the piece evokes a skull or perhaps an abstracted mushroom cloud. To the artist’s credit we are encouraged to circumnavigate the work and form our own thoughts and associations.

Typically, Moore is a poetic dream maker and shadow catcher. The artist allows opportunity for us to merge with and become a part of the work. It is an important aspect of why this less didactic approach proves to be so fresh and enduring. His work is about asking questions rather than providing easy answers. It is always possible to find something new and emotionally resonating in his work.

A close encounter with a massive roomful of the sculptures at AGO is breathtaking and aesthetically exhausting. It endures for miles and miles and miles.