Social Commentary by Canadian Kent Monkman

Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience

By: Charles Giuliano - May 12, 2019

Our two week tour of Canadian museums started in Montreal, continued in Ottowa, and ended in Toronto. Much was familiar from over the years as well as fresh and challenging since our last visit a decade or so ago.

From a recent interview with Matthew Teitelbaum, the director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, we knew what to anticipate. Before returning to Boston, where he had been a young curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, he was formerly the director of the Art Gallery of Ontario in his native Toronto. Starting as chief curator he was with the AGO for sixteen years.

The most significant change he initiated, which is true for most Canadian museums, comprised the strategy regarding First Nations art and culture.

“I have had a personal interest and a professional interest in the art of First Nations people.” He told me. “I felt for a long time that their history was the history of Canadian art. Under my watch we acquired the first, historical, First Nations art ever. The museum hadn’t collected that material. We integrated First Nations art into displays of Canadian art on a consistent basis. I was very proud and pleased when we hired Gerald McMaster as the head of the Canadian Department. It was the first time a First Nations leader had been appointed to lead a department other than First Nations. The notion of putting his voice in the middle of development of history was very important to me.”

We were intrigued to see how this played out. Some museum galleries dedicated to modern and contemporary art juxtapose abstract and indigenous art. There was more contrast than synergy as one navigated from hard edge, formalist paintings to Inuit carving and folk art narratives. Another approach entailed a series of galleries dedicated to contemporary First Nations artists.

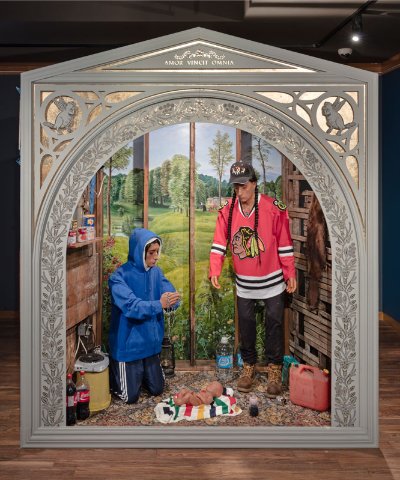

Elements of disjunction in this programming was stood on its head by a sensational, mind-boggling exhibition of the social realist, narrative painter Kent Monkman at the McCord Museum in Montreal.

His provocative and evocative Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience ended on May 5.

The 53-year-old, Manitoba born and Toronto based Cree artist, is creating a mordant, outrageously witty and scathing deconstruction of the horrific treatment of First Nations people in Canadian history.

The narrative style of the oeuvre functions multi-valently. Starting as an abstract artist Monkman had an epiphany while touring the Prado Museum. He came to realize that the tradition of representational history painting could function as a resource for his work.

Teaching representational skills and techniques have generally been abandoned by art schools. Conceptualism and computers have replaced life drawing classes. Thinking in the Duchampian tradition has been prioritzed over acquiring hand/eye coordination.

Becoming a realist painter is easier said than done. It takes time, patience, inspiration, talent and considerable sweat equity to master the academic tradition. Touring the exhibition, and viewing Monkman's website, it is remarkable that he has created such an extensive oeuvre. The attention to detail in the work is daunting. We learned that he has a dozen studio assistants which entails extensive training and supervision.

It is best to come to his work with an extensive background in art history. There are endless quotes from 19th century American landscape painters. Consider a send up of Caravaggio’s “Death of the Virgin” or take off on the iconic “Death of General Wolf” by Benjamin West. A very gay looking matador faces a Picassoesque raging bull.

There are thin lines between borrowed, influenced and plagiarized.

Consider, for example, one of several figurative sculptures. In “Scent of a Beaver” there is a woman (typically for Monkman a transgendered individual) on a swing. It references the rococo French painter Fragonard. This Colonial lady is being gently swayed back and forth by, on one side a French gentleman, and on the other a British one. This costumed work too precisely evoked the post-colonialist deconstructions of the well known British artist Yinka Shinobare.

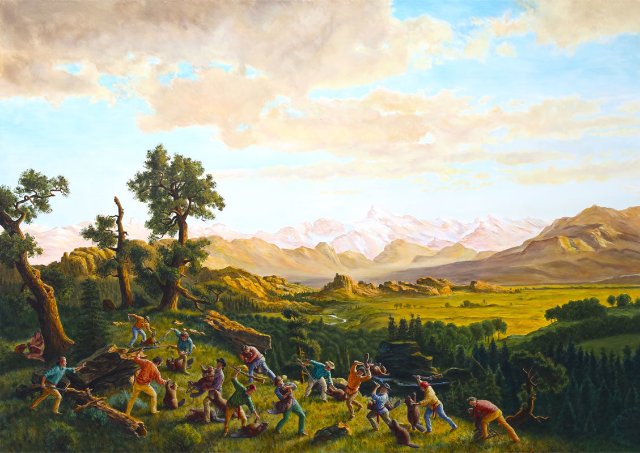

A landscape that evokes an Albert Bierstandt craggy view of the Yosemite drew uneasy comparisons. Monkman captures the look of a Bierstadt painting but without its sublime, subtle precision. The setting provides a prop/staging for the artist’s over-the-top caricature of hapless frontiersmen being buggered by bears.

In another ersatz Bierdtadt “Massacre of the Innocents” frontiersmen are slaughtering baby bears. Art history kicks in evoking a treatment of that subject by Nicolas Poussin.

The impact of Monkman’s work is more evocative when the source material is less familiar.

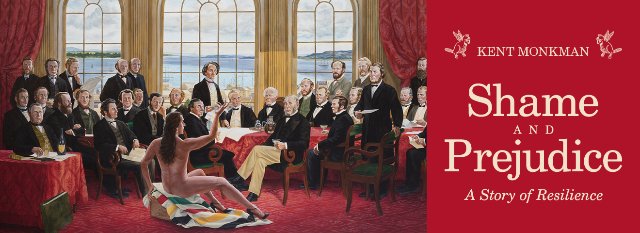

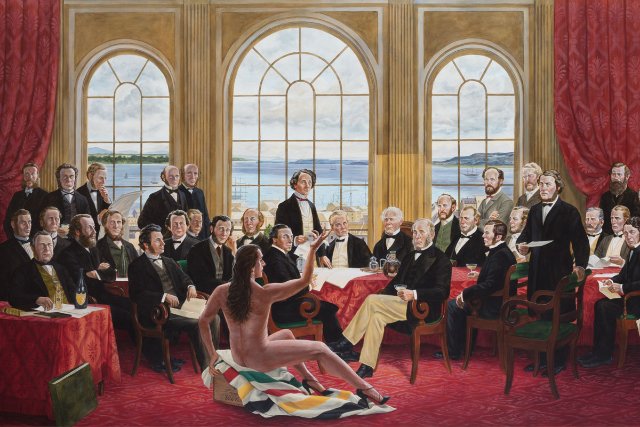

The centerpiece and poster for the exhibition is “The Daddies” based on Robert Harris’s painting “The Fathers of Confederation.” A trope of academic history paintings is a group portrait of a defining moment.

That tradition recalls the attempt of Jacques Louis David to render the 20 June 1789 “Oath of the Tennis Court.” It never went beyond a very large cartoon as individuals attending the event were sent to the guillotine. There were similar problems for John Singleton Copley’s “The Collapse of the Earl of Chatham in the House of Lords, 7 July 1778.” There were so many portraits to render that by the time he finished the epic painting nobody could care less.

The notion of “The Daddies” is that no First Nations people were in the room when the politicians carved up Canada into its provinces. Inserted into this august assembly of nation builders is a nude Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. The name playfully conflates “mischief” and “egotistical.” She reclines among the men who gaze upon her with a humorous range of responses. Upon close examination “her” shoulders are too broad and the arms a bit more hairy than feminine.

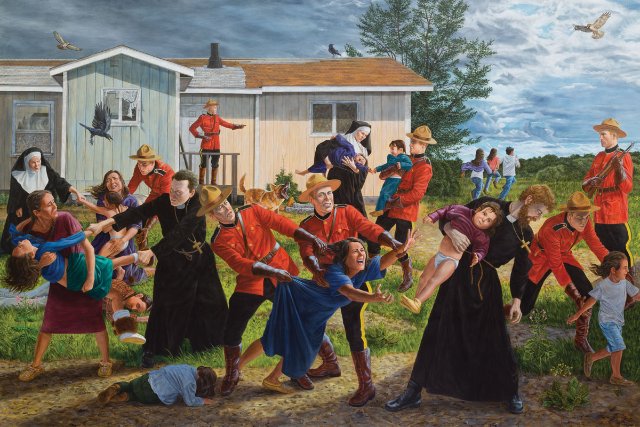

The most compelling painting in the exhibition is “The Scream.” The heart wrenching image depicts First Nations children being snatched from the arms of terrified mothers. They are being abducted by Royal Canadian Police in scarlet uniforms and robed priests and nuns.

In Canada, as well as the United States, indigenous children were forced into boarding schools and orphanages to be Christianized and nationalized. In the South West children were beaten if they spoke native languages. Apache boys were given haircuts and forced to wear school uniforms. Their heritage and traditions were beaten out of them.

There is no denying the power of this painting which reveals the artist at his best. On line we experienced a number of works with similar impact.

Things fall apart and come unglued when the spike heels of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle trip over his/her mixed metaphors. This is most problematic in urban street scenes where the artist creates a mélange of mayhem, violence, matadors, angels and tongue-in-chic cubism.

The paintings of Monkman bring front and center all the critical pros and cons of agit-prop art from David and Goya, to Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Jack Levine or Jack Beal. There is always the delicate synergy between the narrative of a concerned artist and the aesthetic quality of the work itself.

When these elements align the works of Monkman knock your socks off.