The Flying Dutchman at Boston Lyric Opera

Closes Season With American Premiere of 1841 Critical Edition

By: David Bonetti - May 07, 2013

The Flying Dutchman (Der Fliegende Holländer)

Music and libretto by Richard Wagner, after a text by Heinrich Heine

U.S. Premiere of 1841 critical edition

Conductor: David Angus

Stage director: David Cavanagh

Set and costume designer: John Conklin

Lighting designer: Christopher Akerlind

Cast (in order of vocal appearance):

Gregory Frank (Donald); Alan Schneider (The Steersman); Alfred Walker (The Dutchman); Ann McMahon Quintero (Mary); Allison Oakes (Senta); Chad Shelton (George)

Boston Lyric Opera Orchestra

Boston Lyric Opera Chorus

Boston Lyric Opera

Shubert Theatre, April 26, 28, May 1, 3, 5

The Boston Lyric Opera ended its 2012-2013 season with what must be reckoned as one of its greatest successes. Its presentation of Richard Wagner’s early work, “The Flying Dutchman,” his first mature success, to commemorate the bicentennial of the composer’s birth, was not only one of the largest productions in its history, but it was the U.S. premiere of a newly prepared critical edition of the work. The production was musically exciting, featuring the crack BLO Orchestra and Chorus and the big-voiced vocalists Wagner at every stage of his career demanded, and it was inventively, if not flawlessly staged.

The choice of which edition of an opera a company chooses to produce is often of little interest to the audience, which comes to the theater to hear the music and experience the story the opera has to tell. But in this case, the new edition, essentially Wagner’s first completed version of the work, makes a big difference. As music director David Angus explains in a program note, the standard edition of the work produced today is the result of a score assembled in 1896 by conductor Felix Weingartner from several different versions of the work. As he reworked the opera over the years, Wagner frequently changed it, intentionally making it seem that he had composed in his mature manner earlier than he actually had. The original work, written in 1841, was never produced as Wagner at the time intended, the BLO giving it for the first time in the United States.

Wagner isn’t the only composer who rewrote his early works to better fit the fashions of a later time. Rossini was constantly updating his works as they moved from house to house. Even Verdi rewrote earlier works, endowing them with his more mature ideas. The version of “Simon Boccanegra” produced today, for instance, is a substantial rewriting of a work created more than 20 years earlier that Verdi found “monotonous and cold,” but with too many good parts to abandon.

In the 1841 edition, the action is set in Scotland; in subsequent editions, dating from the work’s 1843 stage premiere, it is set in Norway. The names of the characters Donald and George were changed to Daland and Eric. More important were changes to the overture and the opera’s ending. Angus, who did his homework to prepare this production, says that the original overture was relentless in its rush to its conclusion. In the version that has become standard, the slowed tempo of what is known as Senta’s motif robs the overture of its drive. Dramatically, the greatest change is to the ending. In the standard version, Senta joins the Dutchman in death, both of them rising together from the sea. In the original – spoiler alert! – she kills herself and there is no redemption of either the Dutchman or herself.

What is most noticeable – and most agreeable – about the 1841 edition is the lighter texture of the orchestration. This is a work that doesn’t compete with the heavier orchestration of Wagner’s later works – it doesn’t know that those works will exist. The result is an opera closer in spirit to Carl Maria von Weber’s “Der Freischütz” (The Free-Shooter) or even Italian bel canto than to “Götterdämmerung” (The Death of the Gods). Not that the dramatic themes lack in Wagnerian portentousness. Both the Dutchman and Senta, the woman who might redeem him from his endless wandering, seek death as a release from earthly existence in a number of arias, and there is the issue of gold-based greed. Donald is willing to marry his daughter to a dubious character because he is offered all his treasure – shades of Alberich from “Das Rheingold,” the first installment of the overwrought Ring Cycle.

The story is a legend that was familiar in Wagner’s day. The Dutchman is a sea captain who, tempting fate, has been condemned to sail the seas for eternity unless he finds a woman who will love him. He is given a reprieve from his wandering every seven years for one day to find that woman. The story of the opera takes place during that day. Senta, the daughter of a sea captain, and betrothed to the hunter George, is smitten with a picture of the Dutchman and when he comes home with her father for the night, asking for her hand in marriage, she forsakes George for him. George tries to win her back, reminding her of her vow. The Dutchman overhears their conversation, and mistaking its import, thinks he has been ditched and leaves on his ship. Senta then slits her throat.

Wagner’s rich and dramatic music vividly brings the story to life. Certainly no one before him – and maybe only Verdi in the opening scene of “Otello” and Debussy in his tone poem “La Mer” after – wrote music more evocative of the sea, wild, churning and crashing in storm and ominous even in calm. After an overture that interweaves many of the opera’s themes or motifs, the opera opens during a storm that has imperiled Donald’s ship. The force and danger of the sea is never long absent during the rest of the work.

From the opening chords, it was apparent that the BLO orchestra was playing at a fever pitch, conductor Angus driving them to ever-greater heights.

(By the way, I had to miss the press opening because of a cold that wouldn’t go away and I recovered enough to go out only in time for the final matinee, when I purchased a seat in the balcony; I must report that the sound there is the best I’ve heard at the Shubert. It’s not unusual for balconies to have the best sound in an opera house. In San Francisco, where the house has 3,500 seats, the choice is to hear best or to see best. Only the very most expensive seats in the boxes offer both. The Shubert has only 1,500 seats, so a balcony seat not only offers superior sound, but also great visibility.)

With its lighter orchestral texture, it becomes apparent that “The Flying Dutchman” is to a great extent a ballad-opera. In the first scene, the Steersman sings a lovely ballad to his maiden dear. In her big second act aria, Senta sings a long ballad that tells the tale of the Flying Dutchman. And the virile sailors choruses have a ballad quality to them as well.

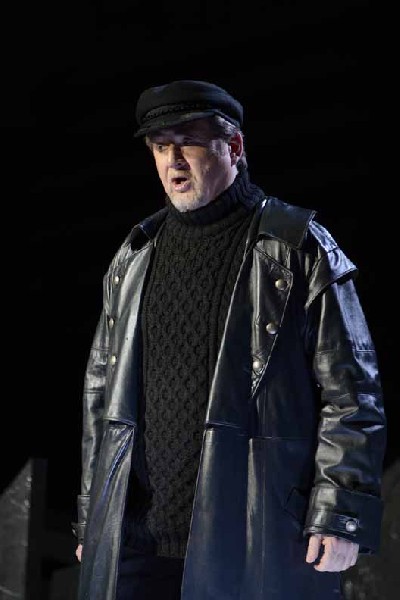

For the work, the BLO has assembled an extraordinary cast of Wagnerians. Taking top honors is the Dutchman of Alfred Walker, whose deep bass-baritone is warm and flexible with the occasional sweet top notes. At the end of the work, when he reveals that he is the Flying Dutchman, the quiet power of his voice was chilling. Walker, who sang Porgy in the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s “Porgy and Bess” last year, sings at the Met and La Scala, and it was an event to have him here twice in one season. Walker was nearly matched by bass Gregory Frank as Donald, Senta’s greedy father. Rarely do you get low male voices able to clearly articulate the text. Here, with Walker and Frank, there were two. As George, tenor Chad Shelton was sweet voiced but dramatic. His singing and acting were particularly powerful in the third act, when he confronted Senta about her vow of love to him. As the steersman, Alan Schneider sang his ballad with the sweet longing of youth. Mary Ann Quintero in the small role of Mary, Senta’s nurse, was fine.

Allison Oakes as Senta was problematic. A dramatic soprano in the Wagnerian mold, her voice was unpleasantly metallic when forced, and she forced it frequently. At the end when she slits her throat I was surprised not to hear the orchestra make a sound of metal hitting metal. Still, a friend I met after the performance praised her performance, comparing her to the great Wagnerian of an earlier era Astrid Varnay. Chacun á son goût.

Although the female chorus of fisherwomen was not given much to do, it was fine at what it did. The male chorus of sailors, however, was the backbone of the opera, and justified the larger cast of performers the opera requires. In its first act chorus, it made a thrilling masculine sound, and as a drunken bunch of louts in the third act party scene it captured the menace inherent in out-of-control men.

As designer of both sets and costumes, veteran designer John Conklin was at his best. The set was composed of three moveable constructions that variously served as the deck of a ship, the site of a fish-processing camp and, most impressively, the Dutchman’s ship, with its famous red sails and black mast. Ominous indeed. Costumes were largely drab as they would be in a working fishing village. The sailors and the fisherwomen both wore gray, but the sailors were equipped with bright yellow rubber boots, and in the third act party scene, the men stripped to singlets and the women put on flowery dresses. The Dutchman wore a long silvery gray coat that emphasized the grayness of his countenance. And, marking her apart from her fellow villagers, Senta wore a long dark red gown. As a backdrop, there was a video projection of churning waves by Seaghan McKay that was very effective.

The stage direction of the Canadian Michael Cavanagh worked for the most part, but it included curious elements that were questionable. Like so many of his brethren, he doesn’t seem to know when to leave well enough alone. It has long been the habit of ambitious directors to stage a pantomime during the overture. Since the overture to “The Flying Dutchman” is long, it gave Cavanagh the opportunity to needlessly complicate the story by showing a young Senta brutalized by her father. In all there were two silent Sentas that served as observers during several scenes of the opera – to no apparent purpose. Cavanagh supposedly intended to present Senta as mentally unstable, suggesting that the entire opera is her fantasy or dream. Certainly, she refers to dreams often enough in the text to justify such an interpretation. But he doesn’t need to make Senta seem insane. Wagner makes her seem insane. Isn’t that enough?

The BLO has announced its 2013/14 season, during which it will continue to follow its formula of three main stage productions, mainly warhorses, with one smaller scale, ostensibly adventurous, “Opera Annex” production. The main stage productions will be Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” (October 4-13) in a new English translation, Verdi’s “Rigoletto” (March 14 to 23) and Bellini’s “I Puritani” (May 2 to 11). The annex production will be a chamber version of Jack Beeson’s “Lizzie Borden” especially commissioned by the BLO from the composer. The good news is that Sarah Coburn and John Tessier who so scintillated in the BLO’s production of “Il Barbiere di Siviglia” will star in “I Puritani.” And even better news is that neither “Rigoletto” nor “I Puritani” will be done in a new English translation. We’re not in St. Louis, are we?