Dohnányi and Paul Lewis at Chicago Symphony

A Prelude to Tanglewood July 24th

By: Susan Hall - May 05, 2014

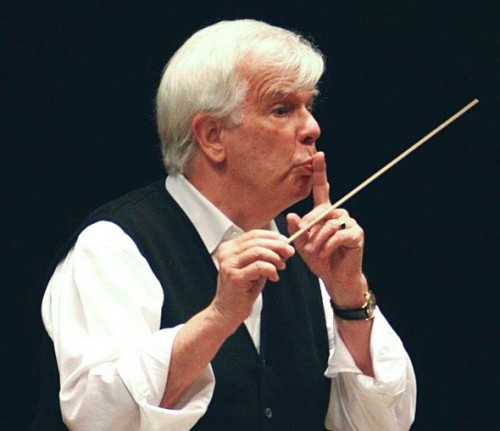

The audience and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra worked hard at a dress rehearsal for a program that included the Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3. Christoph von Dohnányi is a sought after conductor the world over and it is easy to understand why. Instrumentalists respect and enjoy working with him, even though a flautist in the CSO turned a bright red in the face trying to execute a passage to the Maestro’s taste. Dohnányi was in Chicago for a three-day stint which included a fascinating performance of Lutoslawski's Musicque Funebre and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6.

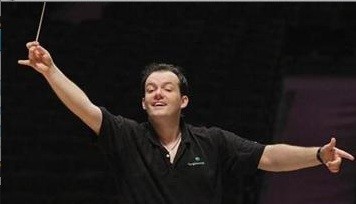

Paul Lewis joined the Maestro as pianist in a stunning performance of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto.

Lewis is simply wonderful. A tall, long man, with a mop of curly hair, his demeanor is serene. He wore Dockers gimball style (how did he depress pedals in these, whose soles have always felt inflexible). He opened by tapping the pedals as the CSO introduced Beethoven, listening to the orchestra with seeming calm and rapt attention.

I immediately noticed his huge hands. I suppose you could stumble over long fingers when you are playing intricate Brahms, but Lewis appeared to find only an advantage in his fingers and an exceptionally large hand span.

Lewis has complete command of the force with which he strikes a note, but also plays with subtly. The runs are perfectly even and breathe as they ascend and descend. Big chords and dramatic punctuation are effortless. Yet Dohnányi likes whispers and he got them from Lewis in spades.

Lewis springs the rhythms and there is a flexibility and dynamism that keeps our attention without any exaggerated comic gestures. The power is natural, never forced.

Between the Maestro and his soloist, there were warm exchanges of appreciation and pleasure, a remarkable human encounter. Electricity was in the air.

Lewis’ mentor Alfred Brendel has said, "If I belong to a tradition it is a tradition that makes the masterpiece tell the performer what he should do and not the performer telling the piece what it should be like, or the composer what he ought to have composed." (Debussy and others have said this too).

Lewis says, “I think what you’re doing is… trying to unearth what it is that Beethoven was getting at.you’re trying to do is to convey what it is you think Beethoven is telling you." While Lewis plays with a freedom, he talks about sounding unrestrained, and unshackled even in the service of the composer. He continues, "...something, which I suppose requires a different approach but essentially, you’re still approaching it in the same way."

Here is the trick Lewis’ immediacy: the fervor comes from deep understanding and empathy.

Those of us who believe that the world will be a better place if classical music can survive look around constantly for answers to how. It is clear that the Boston Symphony, in hiring Andris Nelsons, a gifted conductor whose commitment to music fills the air around him, is preparing. Nelsons will hopefully bring in young people for the pleasure of live performance.

Nelsons, (and for that matter Muti, Conlon, and Dohnányi) are thrilling maestros who clearly deliver music as it was envisaged by the composer, and not some fun house mirror image of themselves conducting – hair flying, body movements which have nothing to do with a musical phrase.

This is surely one piece of the puzzle as we move into the future. Brendel also says that "humor is the sublime in reverse." Nelson is very funny, and the exchanges between Lewis and Dohnányi at rehearsal suggest that they too see both the humor and the sublime as they perform. A magical approach that appeals across the boards.

Those who heard Lewis in Ozawa Hall last summer will return for his lyrical and joyful music making. Catch his spontaneity and freshness under Maestro Nelsons in Birmingham on June 15th and then in the Shed at Tanglewood on July 24th.