Goya and Steve Mumford Depict War Horrors

Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts Through June 8

By: Charles Giuliano - May 04, 2014

Goya: The Disasters of War is a collaboration of the Pomona College Museum of Art and the University Museums of the University of Delaware. It is curated by Janis Tomlinson, Director, University Museums, and circulated by the Pomona College Museum of Art.

Steve Mumford’s War Journals, 2003–2013 was organized by Mark Scala, chief curator, Frist Center for the Visual Arts. The exhibitions remain on view in Nashville through June 8.

The Disasters of War (Spanish: Los Desastres de la Guerra) are a series of 82 prints created between 1810 and 1820 by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746–1828).

A complete set of Goya’s images are on view at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts. They form a prelude to galleries displaying a more recent depiction of the perennial theme Steve Mumford’s War Journals, 2003–2013.

Like many Spanish liberals Goya embraced the enlightenment and French Revolution which evoked the possibility of ending the tyranny of monarchy. His many portraits of the royal family skewered their idiocy and hypocrisy.

But any fantasies he harbored regarding Napoleon as a liberator vanished during the horrors of the French invasion and the 1808 Dos de Mayo Uprising. The Royal Bourbon family fled to Portugal but were restored to power following the Peninsular War of 1808–14.

The Prado Museum in Madrid displays his epic paintings Second of May 1808, also known as The Charge of the Mamelukes and The Third of May. The first painting depicts poorly armed citizens defending themselves from charging mercenaries. The consequences of patriotism are the subject of the image from the next day when executions were enacted round the clock. The artist includes a humble friar among those executed.

Goya was in poor health and almost deaf when, at 62, he began work on the prints. They were not published until 1863, 35 years after his death. Over a thousand sets have been printed of varying quality.

His handwritten title on an album given to a friend reads: Fatal consequences of Spain's bloody war with Bonaparte, and other emphatic caprices (Spanish: Fatales consequencias de la sangrienta guerra en España con Buonaparte, Y otros caprichos enfáticos).

It is always sobering to view Goya’s images which represent a paradigm for depicting the horrors of war. Uniquely the series includes atrocities that we assume the artist observed first hand. There are also surreal indictments that capture the irony of war and invasion.

Other than captions for the individual prints there is no surviving text of the artist’s thoughts. It is up to art historians to separate fact from fantasy in the series. The atrocities represented are entirely plausible and a tragic aspect of all wars. It is the universality and objectivity of his mordant imagery that resonates powerfully as each new generation confronts the wars and atrocities of their era.

Many artists have been inspired by Goya’s withering indictment of the inhumanity of Napoleon’s army. The German artist, Otto Dix, created a powerful series of prints from his experience as a soldier during World War I. Picasso’s Guernica is an iconic response to the bombing of a Spanish village by German planes used by Franco’s fascists.

We must now add Steve Mumford to the list of great artists who have responded to the challenge of depicting war.

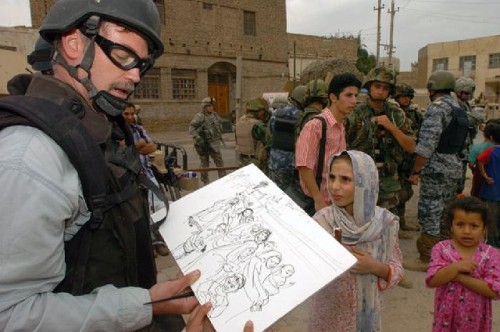

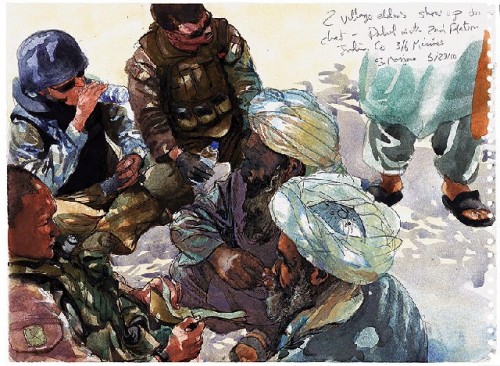

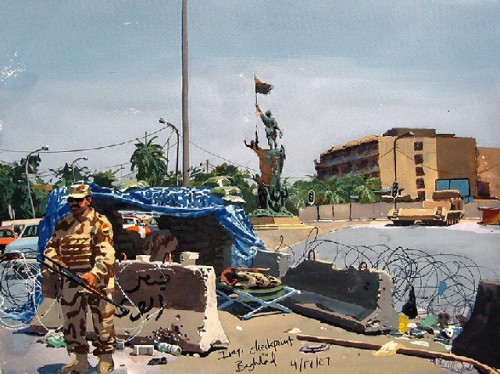

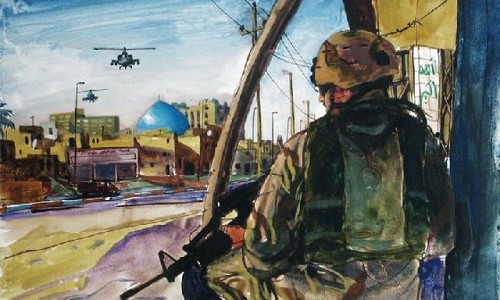

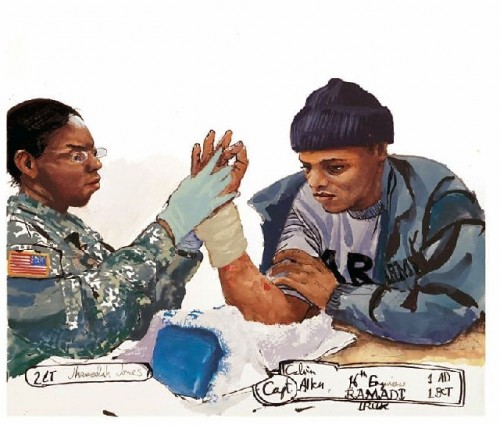

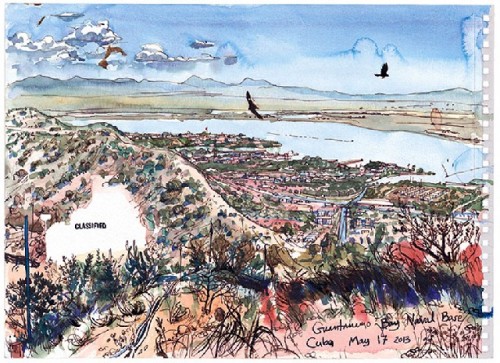

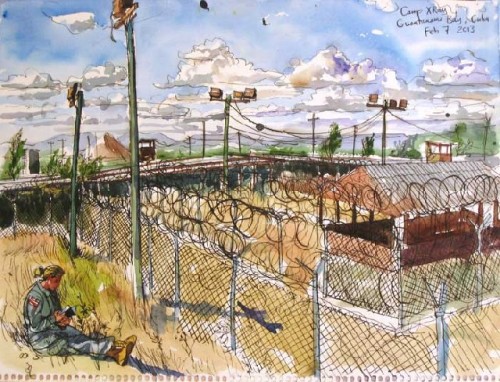

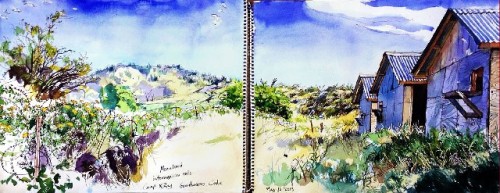

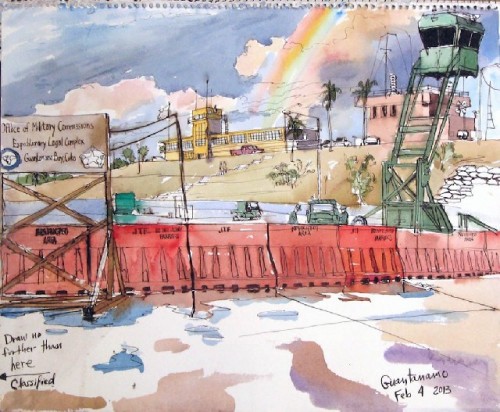

From 2003 until 2013, the artist traveled to war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan, stateside military hospitals, as well as to the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, to create artworks documenting the experiences of American troops, civilians caught in the conflict, and prisoners.

He first entered Iraq from Kuwait on April 15, 2003, approximately one week after Baghdad had fallen to American forces. Mumford stayed for five weeks on his first trip, and returned often over the next eight years, creating in-depth journals of his travels. Some of these writings, sketches, and watercolors, known as “Baghdad Journal,” were presented in installments through artnet.com.

Discussing the project the artist said “Making a drawing is more about lingering with a place and editing the scene in a wholly subjective way. It’s never comprehensive of the visual facts, which are filtered through one’s senses, selected, exaggerated, or left out over the hour or so it takes to make a drawing... . For me, the act of drawing slowed down the war, recording the spaces in between the bombs… I figured since I had never been in a war zone that I would just see how it went, see what my comfort level was and see if I could even draw in that situation.”

The artist, now 53, graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and pursued a master’s degree at the School of Visual Arts.

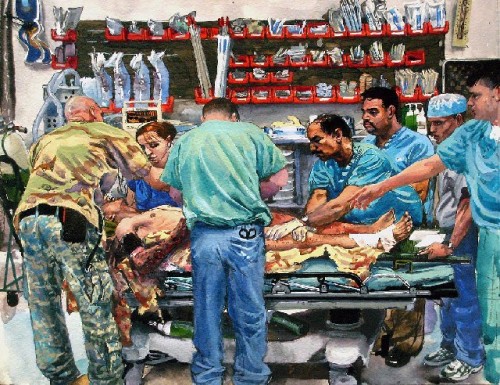

Touring the galleries of the Frist one was astonished by the freshness, intensity and editorial provocation of the works. It entails astonishing discipline and craft to execute such spontaneous field sketches using pen and watercolor. In that sense, as purely eye witness accounts, they have even more veracity than Goya’s studio creations. The technique of Mumford emulates and rivals that of a camera.

Wearing full combat gear, but armed with artist materials rather then weapons, Mumford conveys the reality of reporting from a war zone. Artists don’t get any special dispensation from enemy snipers and he comments on being shot at frequently.

In addition to being embedded with the military Mumford poignantly extends the project to studies in hospitals and wounded veterans in rehab often with artificial limbs.

Yet again it conveyed the injustice that old men send young ones to war.

This is particularly relevant as our nation remains divided in its social and political responses to foreign wars that have now lasted far too long with “allies” that we don’t trust.

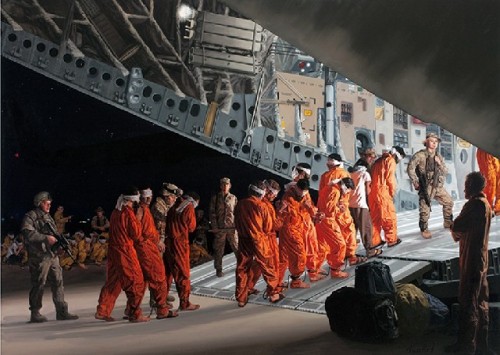

The ambivalence of the nation’s moral compass is further exacerbated by the unconstitutional incarcerations of alleged terrorists at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base.

The one large super realist painting in the exhibition depicts blindfolded, barefoot prisoners in orange coveralls being loaded onto a transport for delivery to Guantánamo.

It is fair and accurate to say that some but not all of these prisoners who have been denied their day in court are terrorists mandated to kill Americans. It is also true that many have been tortured, water boarded, and subjected to treatment prohibited by the Geneva Convention guidelines for prisoners of war. The loophole, also evoked by Great Britain against the IRA, is that terrorists are not soldiers and are thereby denied legal protection.

Under the broad mandates of Homeland Security any American may be declared a terrorist and denied constitutional rights. Be careful what you say on the phone, through e mail and social media. It is perfectly clear that Big Brother is watching. Hopefully, to keep us all safe from acts of terrorism.

We draw our own conclusions about Mumford’s images which do not editorialize on what they represent. They do not convey right and wrong. There is no blame game. We are allowed to observe and look deeply at truly disturbing images.

Significantly the exhibition has been used as potent therapy sessions for veterans with war injuries and PTSD. In some instances it unlocked dialogues with individuals previously incapable of speaking about their traumas.

The transition between the segments of Goya and Mumford is particularly resonant. While Goya’s prints convey the paradigms of war the series by Mumford fast forwards to the here and now.

For many Americans in states of apathy and denial this tandem of exhibitions makes all too vivid atrocities and suffering that we don’t want to deal with. Mumford brings the wars back home in a manner that vividly impacts and changes hearts and minds.