Munch Is a Scream

Agita Sells for a Cool $120 Million

By: Charles Giuliano - May 03, 2012

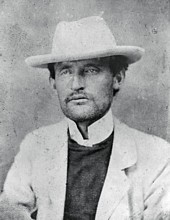

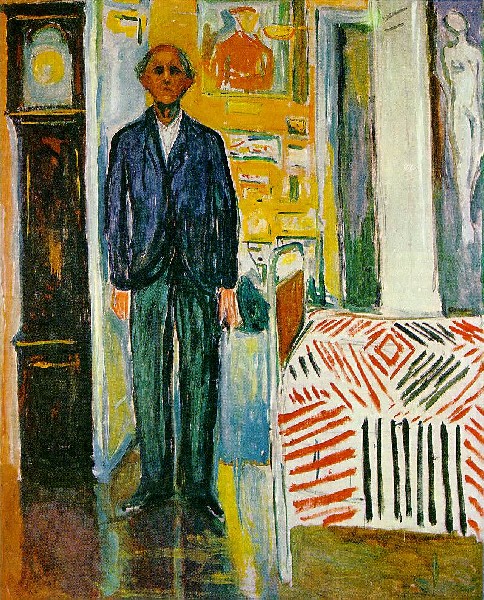

For Edvard Munch (December 12, 1863 to January 23, 1944) the glass was half empty.

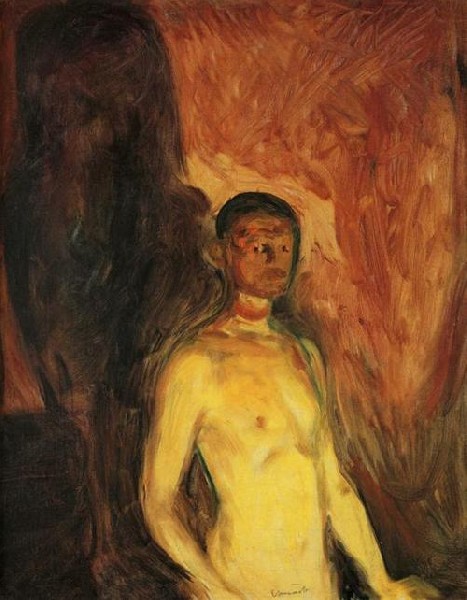

Considering that the artist suffered from depression, alcoholism, belligerence, failed relationships, sickness, family illness, and contemplation of suicide one wonders what he would think about setting a benchmark for art auction sales.

"I live with the dead—my mother, my sister, my grandfather, my father…Kill yourself and then it's over. Why live?"he wrote.

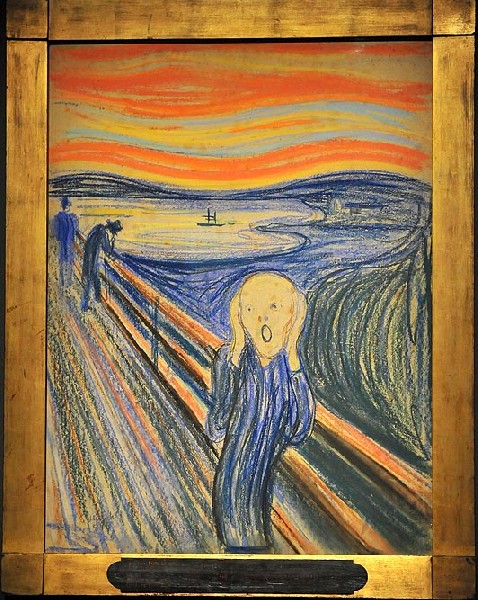

Starting in 1893, at the age of 30, the Norwegian artist created four versions of “The Scream.” The only one still in private hands, a pastel on board from 1895, was auctioned this week for what is rounded off at $120 million. It was sold by Petter Olsen, a Norwegian businessman and shipping heir whose father was a friend, neighbor and patron of the artist.

The impressive selling price, however, is less than half the cost for Cezanne’s “The Card Players.”

In 2011, the tiny, oil-rich nation of Qatar through a private sale purchased a Paul Cézanne “The Card Players” for more than $250 million. There are four other “Card Players” in the series and they are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Musée d’Orsay, the Courtauld, and the Barnes Foundation.

In my opinion the Qatar picture, a more simple composition which depicts two players, is of lesser significance than the Met’s version. It was given to the New York museum, in addition to other major modern masterpieces, by Stephen C. Clark. He was the brother of Sterling Clark who, with his wife Francine, founded the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass.

The record price for the Munch painting is conformation of its iconic status. It is also why works by the artist are targeted for theft and mischief.

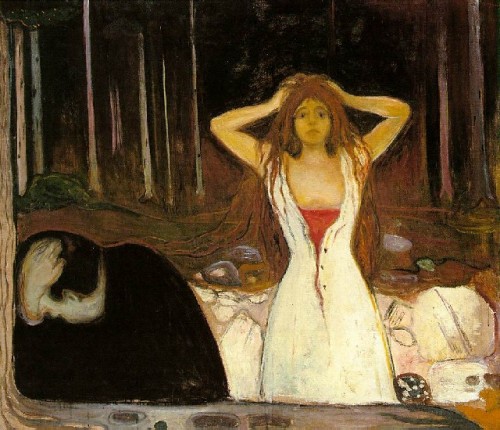

One version of “The Scream” was stolen from the National Gallery (Norway) in 1994. In 2004 another version of “The Scream” along with one of “Madonna” were stolen from the Munch Museum in a daring daylight robbery. All were eventually recovered, but the paintings stolen in the 2004 robbery were extensively damaged. They have been meticulously restored and are on display again. Three Munch works were stolen from the Hotel Refsnes Gods in 2005. They were shortly recovered, although one of the works was damaged during the robbery.

About creating “The Scream” Munch stated "I was walking down the road with two friends when the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence, feeling unspeakably tired. Tongues of fire and blood stretched over the bluish black fjord. My friends went on walking, while I lagged behind, shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous, infinite scream of nature." He later described the personal anguish behind the painting, "For several years I was almost mad… You know my picture, 'The Scream?' I was stretched to the limit—nature was screaming in my blood… After that I gave up hope ever of being able to love again."

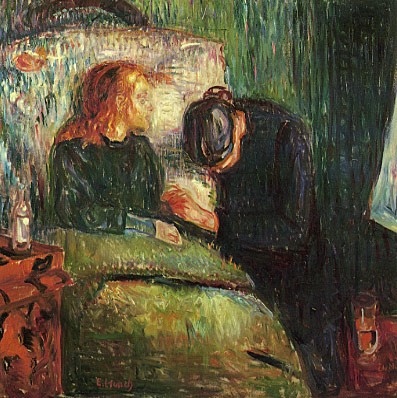

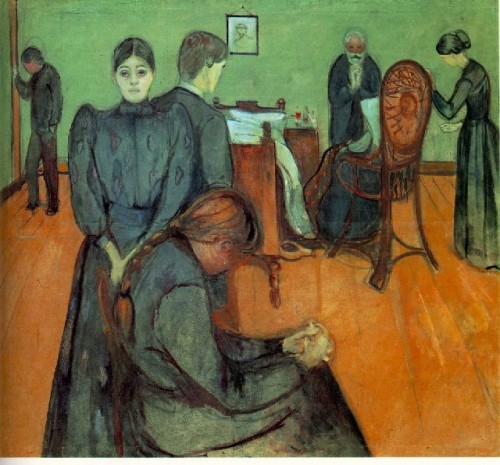

Because the works were so much about self discovery the artist was reluctant to part with them. In mid and later career there were commissions for portraits and he had private collectors. When the Nazis occupied Norway, in 1940, there was concern that his work, which had been condemned by Hitler and included in the famous Degenerate Art exhibition, would be confiscated and destroyed. Seventy-one of the paintings previously taken by the Nazis had found their way back to Norway through purchase by collectors (the other eleven were never recovered), including “The Scream” and “The Sick Child” and they too were hidden from the Nazis.

When Munch died, his remaining works were bequeathed to the city of Oslo, which built the Munch Museum at Tøyen (it opened in 1963). The museum hosts a collection of approximately 1,100 paintings, 4,500 drawings, and 18,000 prints, the broadest collection of his works in the world. The Munch Museum currently serves at Munch's official Estate.

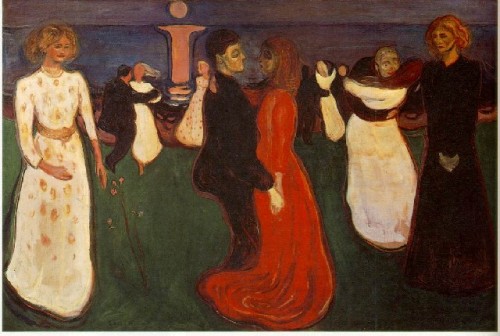

It is common to think of Munch as an expressionist. His mature style predates the formation of Die Brucke in 1905. He had close ties with German artists and enjoyed his first success/ controversy there. In 1892, Adelsteen Normann, on behalf of the Union of Berlin Artists invited Munch to exhibit at its November exhibition. It was the society's first one-man exhibition. There was controversy and after one week the exhibition closed.In response Munch stated that "Never have I had such an amusing time—it's incredible that something as innocent as painting should have created such a stir."

In 1864, his father Christian Munch was appointed medical officer at Akershus Fortress. Edvard's mother died of tuberculosis in 1868, as did Munch's favorite sister Johanne Sophie in 1877. After their mother's death, the Munch siblings were raised by their father and their aunt Karen. Often ill for much of the winters and kept out of school, Edvard would draw and received tutoring. Christian instructed his son in history and literature, and entertained the children with ghost-stories and tales of Edgar Allan Poe.

Against the wishes of his father Edvard enrolled in art school. As a student he was influenced by Hans Jæger who believed that "A passion to destroy is also a creative passion" and advocated suicide as freedom. Munch stated that "My ideas developed under the influence of the bohemians or rather under Hans Jaeger. Many people have mistakenly claimed that my ideas were formed under the influence of Strindberg and the Germans…but that is wrong. They had already been formed by then."[

As a teenager visiting the Museum of Fine Arts one of my favorite works was Munch’s “Summer’s Night Dream” 1893. The museum is notorious for its snub of modernism. The exception was Boston’s interest in Northern European art and expressionism. Under its former director, Perry T. Rathbone, who had known Max Beckmann in St. Louis, the MFA made some key expressionist acquisitions. During WWII the Institute of Contemporary Art showed Kokoschka who taught for a semester at The School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Later ICA director Thomas Messer, before leaving for the Guggenheim, mounted the first American museum exhibition of Egon Schiele. Harvard’s Busch Reisinger Museum bought works that the Nazis auctioned in Switzerland.

In theories of art history there is a dichotomy between The Apollonian and Dionysian. Another way of expressing this is the contrast between the Classical and Romantic. There is a geographic demarcation with Northern European art reflecting the Gothic traditions with their emphasis on sin and the horrific tortures of the damned. And the Mediterranean, sun saturated, optimism of the Classical approach with an emphasis on Apollonian beauty and high aesthetics.

The controversial African American professor, Leonard Jeffries, vulgarized this philosophical debate as contrasting the Eurocentric “Ice People” and the Afrocentric “Sun People.”

Psychologists and sociologists have attributed long cold winters and lack of sun to chronic depression, alcoholism, and suicide among the peoples of the far North.

Those notions would seem to fix Munch in the epicenter of that paradigm.

It is also a key to understanding the universal appeal of his angst driven imagery. Arguably it is more intuitive to emphasize with the suffering Christ than to comprehend and celebrate the joy of His Resurrection.

As an adolescent, for example, it was intuitive to develop a deep passion for the art of Munch and the expressionists or the literature of Camus’s “The Stranger” and the grotesque short stories of Kafka or Edgar Allen Poe.

It was anything but instinctive to relate to Cezanne, the Cubism of Picasso and Braque, the abstractions of Malevich, Kandinsky and Mondrian. Or the sublime whimsy of Duchamp.

Those are acquired skills resulting from discipline, study and intellectual rigor. There are no such requirements to emotionally connect with expressionism.

The sturm und drang plays well with adolescents and the general public. Which is why Munch and van Gogh, undeniably great artists, are an easy sell.

As we discovered several years ago during a visit to the Shanghai Art Museum. In honor of a state visit by the King of Norway (1997) there was a special exhibition of work by Munch.

We were astonished to see so many great works in China. But more so by the throngs of school children who, with their teachers, were making copies inspired by the works. Their versions were amusing if not astonishing. When I took photos the playful, laughing kids swarmed around us. It was a mind boggling experience.