Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map

First Retrospective by Native Artist at Whitney Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 29, 2023

Now 82, at long last the Native American artist, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, is the subject of a retrospective at a major New York Museum. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art from April 19 to August 13, 2023.

The museum, which by definition embraces all of American art, has been either slow or reluctant to recognize the work of contemporary Native Americans.

There was backlash to the museum’s first such effort Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, Nov 3, 2017-Jan 28, 2018.

Jimmie Bob Durham (July 10, 1940 – November 17, 2021) was an American sculptor, essayist and poet. He was active in the United States in the civil rights movements of African Americans and Native Americans in the 1960s and 1970s, serving on the central council of the American Indian Movement (AIM).

While Durham enjoyed an international reputation for work grounded in indigenous content and expression its authenticity was widely challenged.

As a November 17, 2021 New York Times obituary stated “But over the years, Cherokee representatives questioned his Native American identity, becoming more vocal as his art became more visible. In June 2017, shortly after his first American museum retrospective, ‘Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World,”’ moved from the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, 10 Cherokee artists, writers and scholars published an opinion piece in Indian Country Today titled ‘Dear Unsuspecting Public, Jimmie Durham Is a Trickster.’

“The article said Mr. Durham was neither ‘enrolled nor eligible for citizenship in any of the three federally recognized and historical Cherokee Tribes.’ It went on to dismiss his being Cherokee in any ‘cultural sense,’ either.”

While the Quick-to-See Smith exhibition may be regarded as too little and too late it may be considered as righting an egregious wrong. She is widely regarded as a major artist of her generation, educator and advocate. In addition to pursuing her own remarkable career she has been an engaged colleague and mentor to an emerging generation of artists.

We met initially by e mail and then in person during a 2005 visit to her studio in Corrales, New Mexico. She was a patient mentor as I networked with, wrote about, and curated an exhibition of her work, created for the occasion, as well as a group exhibition Native New Yorkers.

Her influence was crucial in my engagement with Native American artists. At the time that interest and commitment was shared by few in the mainstream art world. Much has changed since then but American museums lag far behind those in Canada. We encountered seismic changes during a tour of Canadian museums several years ago.

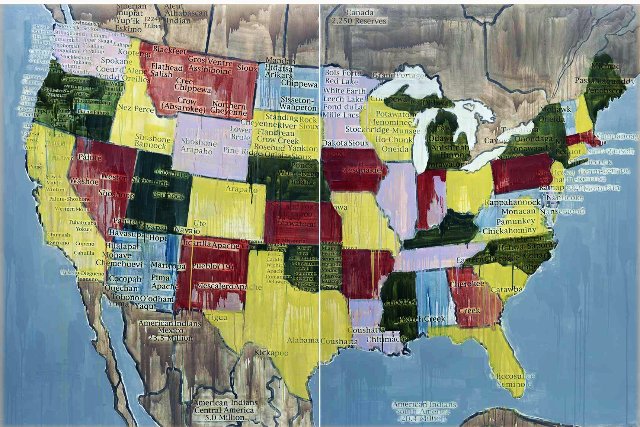

The most significant change was undertaken at the Art Gallery of Ontario under former director Matthew Teitelbaum. In a more incremental manner he is initiating diversity in the collections and strategies as director of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. On September 8, 2020 the MFA announced a major acquisition. ”Artist and activist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith recreates the map of the United States, luring us in with its instantly recognizable shape, only to challenge our preconceptions. Painted in washes of primary colors, deep greens, and soft pinks, Tribal Map recalls the vibrant maps of the United States that hang in elementary school classrooms. Only here, the borders drip and bleed together, suggesting a melting of boundaries. And instead of familiar state names, we see the names of living Indigenous communities—some appear in their homelands, others over the regions where they were forced to migrate. The very title of the work urges viewers to acknowledge the peoples whose histories on this land extend to time immemorial. At the edges of the US, black borders are partially obscured by drips of brown paint and the names of Indigenous communities that spread across national boundaries. The word Wampanoag is collaged over the state of Massachusetts, indicating the people who originally lived here—and continue to do so—rather than referring to the current geographic boundaries. In Wôpanâak (the Wampanoag language), Mâsach8sut means “place of the big hill,” potentially referring to the Blue Hills. Massachusetts is one of many Algonquian words found throughout New England on town placards, street signs, and maps…”

What follows are the Whitney Museum press release and an account of my 2005 studio visit.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map

Whitney Museum of American Art

April 19 to August 13, 2023

This exhibition is the first New York retrospective of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b. 1940, citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation), an overdue but timely look at the work of a groundbreaking artist. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map brings together nearly five decades of Smith’s drawings, prints, paintings, and sculptures in the largest and most comprehensive showing of her career to date.

Smith’s work engages with contemporary modes of making, from her idiosyncratic adoption of abstraction to her reflections on American Pop art and neo-expressionism. These artistic traditions are incorporated and reimagined with concepts rooted in Smith’s own cultural practice, reflecting her belief that her “life’s work involves examining contemporary life in America and interpreting it through Native ideology.” Employing satire and humor, Smith’s art tells stories that flip commonly held conceptions of historical narratives and illuminate absurdities in the formation of dominant culture. Smith’s approach importantly blurs categories and questions why certain visual languages attain recognition, historical privilege, and value.

Across decades and mediums, Smith has deployed and reappropriated ideas of mapping, history, and environmentalism while incorporating personal and collective memories. The retrospective will offer new frameworks in which to consider contemporary Native American art and show how Smith has led and initiated some of the most pressing dialogues around land, racism, and cultural preservation—issues at the forefront of contemporary life and art today.

This exhibition is organized by Laura Phipps, Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, with Caitlin Chaisson, Curatorial Project Assistant.

A 2005 Studio Visit Corrales, New Mexico

It was with great relief that we pulled into the driveway behind a wall along a country road in rural New Mexico near Albuquerque. Finding the home of Jaune Quick to See Smith and her husband, Andy Ambrose, had been a daunting task. Barking but ultimately friendly dogs announced our arrival. Yes the directions were a little tricky but getting them had been a greater challenge. It seems that they almost never answer the phone. An intrusion of their privacy they explained. And although we had communicated by e mail for the past few months, we had departed for the South West without a firm date for meeting or instructions on how to get there.

“Oh, we are more spontaneous here in the west,” she would explain later when we settled into the living room of the adobe house they have lived in for more than a score of years. This summer they plan some renovation and she hopes to start cataloguing the stacked shelves of slides and information gathered from a career in which she has consistently had more that a dozen annual one person and group exhibitions, visited a couple of hundred college campuses, and given numerous keynote addresses to education conferences and women’s groups.

She was just getting off the road from the busy season in which she travels extensively as a visiting artist and lecturer. This culminated in the opening of a one person exhibition at the Flomenhaft Gallery in New York where her work is on view through July 2. She zigged, flew to New York for the opening, on the weekend when we zagged and arrived in Vegas. So it seemed logical to meet the following weekend. But that became ever more tentative as we hoped for a return call on our cell phone. For that coming weekend, when we did finally connect, she was committed to attend the funeral in Kansas City of a friend and art dealer. We scheduled for the following Monday when we actually backtracked after a weekend in Santa Fe.

There is a bit of the mother and schoolmarm in her warm and humorous approach. She was teasing me about being so Eastern and typically hung up on schedules and appointments. That is not the spirit of the casual, laid back West with its wide open spaces. To which I replied that I am not so much Eastern as simply neurotic.

There was much to discuss as I plan to show her work and bring her to Suffolk University as a visiting artist/lecturer during the winter/spring semester of 2006. It was also my first exposure (Astrid had visited the region some years prior) to the South West and its Native American culture. Sure, I had read a lot of the history, and all incoming freshmen this summer are assigned to read the riveting book “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” by Dee Brown, as background for her visit to campus, but I am sensitive to not acting like the usual tourist. I had hoped that she would guide me through to a more accurate take on Native American culture.

Our interaction had started months ago when she sent me an out of the blue e mail response to a Maverick piece (my website that preceded Berkshire Fine Arts). In it she stated that she liked my writing in general even though it is too Eurocentric. My response was an invitation to help me become less so. She welcomed a potential colleague and ally. Despite her great efforts and professional recognition she replied to my statement of commitment that “It is music to my ears.” Later, in her living room, she would confirm and elaborate on those ideas.

First, however, we took a quick tour of the grounds. Andy produced a fading photograph to convey the original appearance of the property. In the chicken coop we encountered some truly exotic species including very strange looking birds from Africa. “Oprah served them at her birthday party,” Jaune commented with some ironic dismay. There were two roosters but she commented that they get along because the number two guy knows his place.

While we are the same age, born 1940, and share a generational overview, our life experiences have been remarkably different. While I grew up the son of doctors, she had her social security card at the age of eight when she and her sister were put to work on the farm of Japanese citizens who had been interned during the war and just recovered their confiscated property. Of Salish, French-Cree and Shoshone ancestry she was born on the Flathead Indian Reservation in St. Ignatius, Montana. I asked if she spoke her native language but she replied that she did not. Her father, a horse trader, had moved off the reservation. She stated that back then native kids were beaten in school when they did not speak English, which was official government policy. Today, much effort is made to sustain these disappearing languages.

Getting an education proved to be a long and difficult process. She was 36 by the time she completed a B.A in Art Education from Framingham State College in Massachusetts. Her husband worked in the computer field in the region while she took evening classes. The Danforth Museum in Framingham mounted a one person show several years ago and Massachusetts College of Art is one of several institutions that have given her honorary degrees. In 1980, she earned an M.A. in Art and Indian Studies from the University of New Mexico.

“I hoped to teach art on a reservation,” she said. “And that was the only Native American Studies program in the country at the time.” At about when she completed her degree, however, her career as an artist took off. Recently, she was offered a full time position in the graduate program of the University of New Mexico. Her response is interesting. “Why are they offering that position to me now, and not twenty years ago when I really could have used it?” It would certainly make life a bit easier teaching a handful of students. But, “As Andy pointed out, I reach hundreds of students in a semester through my travels and lectures. So that is more important and I wouldn’t want to give that up.” Jaune has something to say, and says it. Also, she has been a real mentor particularly to young native artists. She has helped them in many ways including organizing numerous traveling exhibitions. “I know a lot about the art world so I show them basic things like organizing a resume, writing an artist statement, and getting slides together.”

While she has organized and participated in countless exhibitions it is mostly in small, out of way, off the map locations. “If you look at the Art in America Annual index, I am listed in more shows than just about anybody but Picasso,” she said. “But contemporary Native American art continues to be ignored by the mainstream of the art world and museums. There are a number of shows of Native American art traveling but they are all focused on pots, blankets and jewelry. That’s what sells. We are suspect aesthetically if we are not making traditional work. There are few museums collecting our work.” Actually her work is included by such major museum collections as the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Denver Art Museum, the Museum of Mankind in Vienna, and a work was recently acquired by the Hood Museum of Art.

Several years ago she approached the Missoula Museum of Art in Montana in an effort to form a collection of contemporary Native American Art. “I flew up there at my own expense,” she said. “I offered to the museum one print from each edition I published. I offered some $1,500 in cash as seed money if they matched my donation. That may not seem like a lot but it was to me at the time. Then I offered to give them work from my own collection. Native artists like to swap so I have a lot of work. When I offered all that they said they would have to get back to me. It is a small museum with limited resources.” They took the deal.

She also does a lot of work in the field of curriculum and education. “I’m the poster child for art education,” she said. “But when writing high school curriculum they always want to think of us as dead and not as a living presence.”

During our 2,000 mile drive through the South West the truth of her statement was compelling. There were tough encounters with harrowing poverty, whole communities struggling for survival, swept under the rug. The skewed notion is that Indians are getting rich and cashing in on casinos like Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun. It is just another in centuries of myths and lies. How can our government posture about saving the world while so shamelessly neglecting native people and resources?

So, yes, there is irony and rage in her work but tempered by popular imagery, parody and humor. There is a complex confluence of sources. She does not sit comfortably within confines of our coded thinking. Of course she is as likely to know and be influenced by Andy Warhol or Picasso as the petroglphys in an ancient Kiva. She showed us one during a drive to lunch. We climbed down a ladder on a scorching hot day to feel the coolness below the earth. “No woman would be allowed in here,” she told Astrid, indicating where food would be lowered to the men during retreats and ceremonies.

The gallerist, Jacqueline Lloyd, of LewAllen Contemporary in Santa Fe had been enormously helpful in showing us a range of work from posters and drawings to large paintings. The gallery, which recently changed hands, is one of the oldest and most established in the city which is regarded as the second largest art market in America. The generous space which fills two floors is steps from the plaza in the heart of town.

There was not that much new work to see in Jaune’s studio because of the major exhibition now on view in Chelsea. And, while she can talk a blue streak about art, ecology and politics, she is fairly reticent about her own work. When we had questioned Lloyd about the interpretation of some pieces, she said, “You’ll have to ask Jaune about that.” So I did.

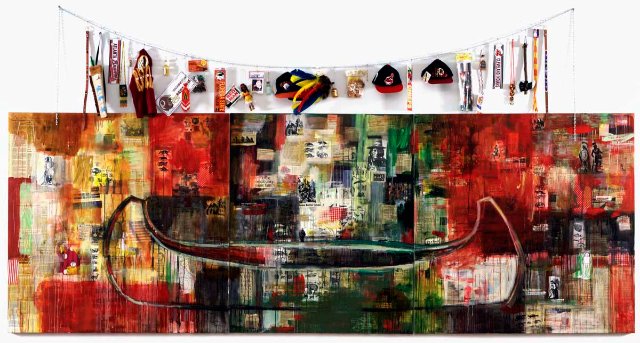

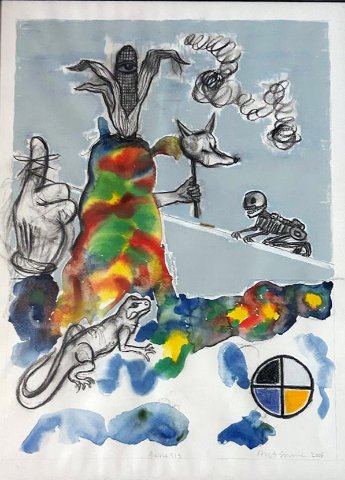

Several new, large, vertical, narrow paintings were propped against the wall in various stages of progress. I was familiar with them from web searches. There is a motif she has been working with that entails either native dress forms, devoid of the figure, or female forms, like a dress maker’s pattern. Around this life-sized central image were a variety of birds and other elements. When pressed she related that they were about censorship, post 9/11, and the Homeland Security Act. The imagery entails suspicion and guarded communication that has resulted in our loosing limbs as a metaphor for loss. Sometimes there is something inside the dress form, a child within, or a skeleton. She is also making a series of epic scaled canoes with a strong anti- war message. Much of her post 9/11 work involves aspects of war and inhumanity but in a universal sense. The work is about all war rather than just this war.

“My art is about the human condition,” she said as we sat in the studio, a separate building next to the house. It is a large, functional, generic space. “What I know is Native American all else just falls into place. I tell a story from my point of view. There is a big divide between Europe and Native American art. Our philosophy and religion is more out of the land itself.”

With such a rich and complex history and culture Jaune would seem to have limitless sources for her work. “Some artists say that they envy me,” she commented. “That it is easy for me to make the work because I come from a tribe and they do not. But I tell them that we all come from a tribe. How can you not know your ancestors and where you come from?”