Cindy Sherman at MoMA

Girls Just Want to Have Fun

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 25, 2012

Cindy Sherman

Museum of Modern Art

Febuary 26 to June 11, 2012

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

July 14 to October 7, 2012

Walker Art Museum, Minneapolis

November 10, 2012 to February 17, 2013

Dallas Museum of Art

March 17 to June 9, 2013

Walking through the galleries of the Museum of Modern Art viewing the 171 photographs by Cindy Sherman (born January 19, 1954), from intimate to mural scaled, is less like a retrospective and more like leafing through an album or scrapbook of family memories.

The images are just that familiar.

You would have to be living on Mars since the 1980s not to be familiar with arguably the most iconic oeuvre of any American artist of her generation.

Movements have waxed and waned, while critics have recorded the volatile seismographs of individual careers, but Sherman has proved exempt from all that. Her unique work, both accessible and amusing with sufficient gravitas, exists outside the topography of the art world’s tectonic changes.

It has a simple and unique premise. Since the mid 1970s she has been photographing herself with a remarkably clever, ever evolving range of themes, settings, props, costumes and personas.

For a career based on photography the mythology informs us that she flunked a required freshman photography class at Buffalo State College. Fortunately, she repeated the course with Barbara Jo Revelle, whom she credits with introducing her to the medium and conceptual art.

To satisfy the concerns of her parents Sherman was pursuing a degree in art education that would qualify her for the security of teaching. She studied painting but was growing apathetic about learning its basics. As a diversion she was exploring thrift shops and amusing herself playing dressup.

Rather than mastering painting and drawing, photography became instant gratification. Initially, it served as a means to an end. She was not so much interested in photography as an art form but rather as a way to record and document the ever expanding range of characters and settings she was inventing.

She was pursuing performance art for the benefit of a camera. While created alone in the studio, or on location, the solitary work, ironically, resulted in an audience with millions of viewers.

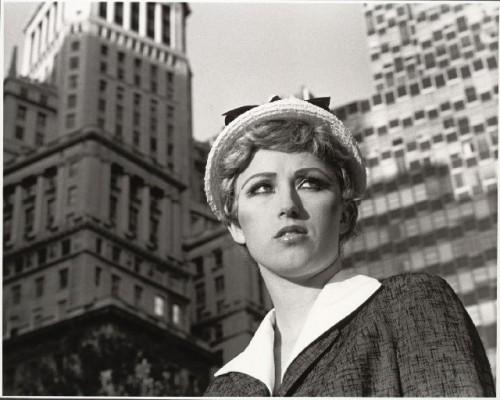

These sessions culminated in the riveting, 69, small format, black and white Untitled Film Stills, (1977–1980). The complete series, acquired by the Museum of Modern Art for about $1 million, is among the 171 photographs in the traveling exhibition which is on view in New York through June 11.

When Sherman was the subject of a 1987 exhibition at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, one of the Film Stills was used for my cover story in Art New England. It depicted her in a slip and wig, on a balcony with a cocktail glass in one hand. The image reminded me of a sexy Italian movie star. It seemed like a good choice to sell the magazine.

There was anxious anticipation as I waited for Sherman to arrive at Metro Pictures for our appointment. Based on many exotic costumes and personas I didn’t know who to expect. What would the real Cindy Sherman be like?

Arriving in generic New Yorker garb, black tights, running shoes and a top she stepped off the street into my life. Briefly. But in an entirely real, engaging, understated and open manner. While just a bit aloof, we were after all perfect strangers, Cindy was amazingly open, unaffected and accessible.

Outside of the context of those remarkable, inventive images she appeared very ordinary. Her fine boned but unremarkable features are a tabula rasa, a blank canvas on which she has the ability to create the most remarkable transformations.

She joked about it. Given her star status she commented about riding around New York on busses. She wondered what a fellow passenger might think to realize that they were sitting next to a celebrity.

A couple of years ago there was an embarrassing reminder of that anonymity. While visiting the ICA I bumped into rock star David Byrne. We happened to be in that light washed area looking out on Boston Harbor. I asked if I might make a photograph. It proved to be quite stunning. He was gracious and charming.

Then I noticed the woman standing silently, a bit sullenly, beside him.

“Oh Cindy, hi” I blurted foolishly.

She was not amused. Probably goes through that a lot when out and about with David. Rock stars trump art stars any day. Hey, my bad.

This time at MoMA I didn’t dwell on the Film Stills. There have been too many such opportunities.

Like visiting the Mona Lisa. Why bother to look? It’s ever detail is etched in memory. Perhaps the Louvre should switch it out with a simulacrum just to test us. They might sell the original to a billionaire and show a hologram. Maybe in 3-D like a retread of The Titanic. If you liked her before you’ll really love her now. Get Peggy of Mad Men to come up with the copy for an ad campaign. Build a virtual reality museum brought to you by Facebook or Google.

Which is to say that the work of Sherman is so familiar, absorbed through regular doses of Metro Pictures exhibitions, that at MoMA you don’t even have to look at it. You can just navigate the galleries and feel the work. Wander through the exhibition on automatic pilot.

Maybe it’s not even about art anymore. The work has tipped over into popular culture, celebrity, spectacle, cosmology and cyberspace.

It begs the question of whether there is anything more to learn about Cindy Sherman?

This edited version of a vast body of work, just 171 images, is the equivalent of a Greatest Hits album. It boils down a dozen albums to a single one. The winners are extracted from their original context. An exhibition, like an album, is created as a suite, a statement with its segues and continuities. You see the whole of the work,

In this selection we get stepping stones that hop through decades of work.

The only other series presented in its entirely is the seminal, 1981, twelve horizontal images known as the Centerfolds. They were commissioned by Ingrid Sichy, then the editor of Art Forum, but never published. What a blunder. They are unquestionably, after the Film Stills, her most singular body of images.

The panoramas present Sherman in believable street clothes, perhaps her last phase of plausible realism, skewering the Playboy inspired, centerfold, male sexual fantasies. Here the women are fragile, vulnerable and enticing for potential exploitation. They are fitful, disturbingly anxious images. They inform the male gaze with signifiers for guilt and shame.

Her further explorations of rape and sexual exploitation would become ever more extreme. Many of the images in the 1987 ICA show were disturbingly grotesque. But that was just the beginning. In the 1989 series Sex inspired by the NEA censorship of grants resulting from congressional reactions to Serrano and Mapplethorpe, her images became strident, violent, and mockingly, ersatz pornographic.

The works in the ICA show slammed me in the face and punched me in the guts. One of the greatest single images of that era is her horrific Pig Snout Woman. It makes no sense not to include it in the MoMA exhibition.

At the time it appeared that Sherman was taking herself out of the picture. Which proved to be true when the Sex series used prosthesis, and porn shop props to create dismembered, disturbing images. It is a period when Sherman was angry and outraged. That provided an uneasy terrain navigated by feminists who seem to have an ever shifting ambivalence to the work.

One of the singular images of the ICA show depicted a large beach scene with sand, and food. Where’s Cindy? Ah, there she is. Grimacing in the reflected surface of sun glasses on the sand. Next to a puddle of vomit. Something terrible is happening.

I asked Cindy about the vomit. She laughed while revealing a studio secret. It was the poured out content of a can of Dinty Moore Beef Stew. It reminded me of the time I encountered a similar puddle of Chef Boyardee, Franco American Spaghetti on a sidewalk of downtown Boston. It had been evacuated so soon after ingestion that it was virtually intact and still steaming.

Thanks Charles for sharing that with us. Hell and art are in the details.

We began by noting that Sherman started as a photographer by default. She derived from the medium just what she needed and not a shred more. Even when successful and wealthy she has continued to work alone in the studio. From a technical point of view, particularly earlier on, she might have employed makeup artists, set designers, lighting designers, camera operators.

It takes an enormous crew and editors, for example, to shoot the actual Playboy centerfolds that Sherman satirically set up and shot solo.

As an autodidact, in more recent years, the work has acquired a richness of sharp, saturated color in ever larger formats. The outer lobby of the MoMA show displays a multi walled panorama of a pantheon of billboard scaled personas.

In those regular Metro Picture shows we tracked the growth and agita of her evolving work.

During one period she burried herself in the painting galleries of the Met and other museums. As research she channeled Flemish, Baroque and Neo Classic portraits, saints, heroes and martyrs. Emulating Memling there was a large bare, prosthesis breast for a suckling infant Jesus. Her studies of male characters, with balding pates, were particularly engaging. A more literal reference to Caravaggio’s early Bacchus misses the mark comparing poorly to the subtlety of the sublime original.

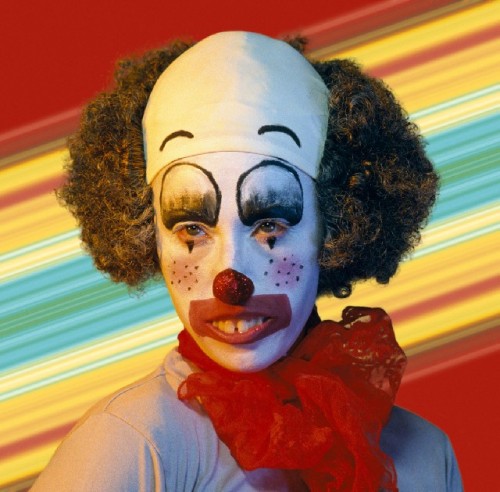

For me the entire Clown series missed the mark. What was its point? As did most of the Head Shots (2000-2002) and what I would call the tough broads.

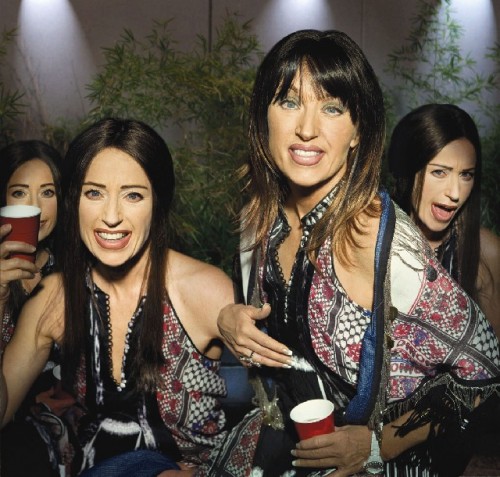

Eventually, Sherman switched from analog to digital. Since she was never much of a dedicated wet photographer it is a logical transition. It also opened up the potential of alterations using photoshop. She also used back projections and photoshop layers to create more elaborate sets for her characters. She was able to build complex images and multiply characters.

This has culminated since 2008 in the Society portraits. There is skewering, mordant wit and screeching satire in sendups of the women of Park Avenue, the Hamptons, and Palm Beach. They convey the pampered, bitchy aura of wealth, privilege and power. Ironically, they convey simulacra of the wives of collectors who buy her work and use it to decorate their mansions and penthouses. Don’t they get the joke? Give Cindy credit for biting the hands that feed her.

By now, perhaps, she is their equal and peer. She likely studies them at upscale social events where she is a prized invited guest. Like Voltaire at the Paris salons. The mega wealthy always seem amused by those who lampoon them. Like that nasty troll Truman Capote.

Oh well Cindy. You’ve come a long way baby from playing dress up in Buffalo to the dinner parties of Park Avenue.

It’s been a great adventure and thanks for the memories. Your work has been the art world’s most sustained and entertaining soap opera.

Incredible.