Myanmar (Burma)

Part Three: Mandalay

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 25, 2010

A 30-minute flight with Air Mandalay brought us from Bagan to Mandalay, the royal city, founded in 1857. On the way into town we made a detour to Inwa, the former royal capital, founded in 1364 and known for its unique monasteries. Passing by child cattle herders and young vendors of straw hats, bracelets and postcards, we reached the dock to cross the Irrawaddy River. As in other places we had seen before, the river banks here were lined with people scrubbing laundry over stone slabs. Transferring to a horse and carriage, we bumped along a dusty country road, admiring small houses on stilts with facades woven from alternating strips of dark and light bamboo.

Our first stop on the carriage ride was at the ruins of the 13th-century Inwa Temple, consisting of tiered brick structures embellished with stone animal statuary. Nearby stood the impressive Bagaya Monastery, built entirely from teak in 1834. The structure has 267 columns made from teak tree trunks, the tallest measuring 60 feet high and 9 feet round. Another 19th-century monastery, Mahar Aung Mye Bon San, distinguished itself with multiple roofs and a seven-tiered prayer hall.

Back in the city we had a delicious lunch at a place called “A Little Bit of Mandalay” and specializing in Burmese cuisine. Here we enjoyed fish and chicken curry accompanied by rice, watercress and green beans. Finally at our Hotel by the Red Canal, we were met by friendly staff, who greeted us with broad smiles and very welcome moist hand towels for cooling off. Set amid lush tropical greenery, with a moat and traditional furnishings reflecting Myanmar’s multi-cultural heritage, the boutique-style hotel accentuated the unique elements of the country. I later found out that the building had been the Chinese Embassy before its transformation into a hotel.

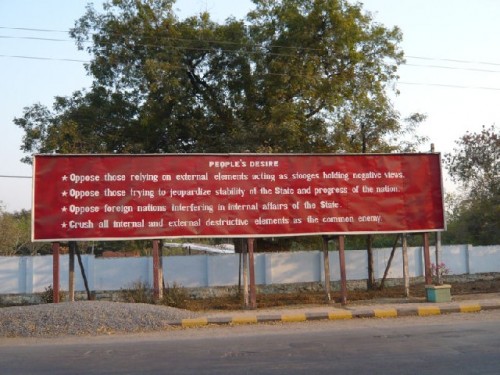

After a rest in our new home for the next two nights, we went back out to explore the city, starting with the former Royal Palace. A landmark of the city, the palace complex was built in 1887 for King Mindon. Surrounded by a moat three kilometers long, it is situated right in the center of Mandalay and is a reminder of the final years of the Burmese kingdom. The palace, made of teak, was burned down by the Japanese in 1945. The government has rebuilt it using modern materials; however, it is now used by the military and, therefore, not open to the public. In 1994, 20,000 citizens of Mandalay were made to clear the moat of mud — a form of forced labor imposed by the junta.

The Shwenandow Monastery is another all-wood building which, fortunately, has survived the ravages of war. It has tall teak columns, ornate carvings and small relief sculptures on all the door panels. The Kuthodaw Pagoda, with its 729 marble slabs, is home to the largest book in the world. King Mindon employed two hundred craftsmen for seven and a half years to carve out the work, known as the Pali Canon, on these slabs. Completed in 1868, each of the slabs has its own whitewashed stupa. In 1871 Mindon convened the Fifth Buddhist Synod in order to consolidate the faith and unite Burmese Buddhists. A team of 2,400 monks recited the complete text of the Tipitaka over a period of six months.

Mandalay Hill is located in the north of the city; it offers a panoramic view of the surrounding region — individual homes to the east of the Red Canal and the crowded south and west, where most people live. It is a favorite place for visitors to watch the sun rise or set. We drove to Mandalay Hill and then climbed ninety steps to the top, crowned by the Su Taung Pyi, or “Wish-Granting” Pagoda. The pagoda was dazzling, with its shimmering mosaic walls and multitude of arches supported by mirrored turquoise columns. People filled glittering shrines to pray for the fulfillment of their wishes. My only wish was for the smog to clear so that I could get a good picture of the panorama below as the sun set. My wish was not granted.

Our hotel by the Red Canal had a welcome party for its guests on a timber-lined deck by the pool. The full bar included rum or gin mixed with our choice of tropical fruit juices. On an outdoor brazier a chef grilled fresh corn, giant okra, and broccoli, and skewered small potatoes on demand, while gracious staff waited on us tirelessly.

The next morning’s local color included people exercising by the canal and saffron-robed monks crowding into pick-up trucks to go to the market and collect their daily meal. We rode a boat up the Irrawaddy River to the village of Mingun to have a glimpse of the local culture. During the hour-long boat ride, we passed by sandbanks dotted with people living in small shacks, some under bamboo mats fastened to posts by the water’s edge. These people make a living by shoveling sand directly into a boat and rowing it across the river to sell to construction sites. In this region live the poorest of Mandalay’s poor.

In Mingun we visited a monastery school, where young boys received their basic education. Often parents trust their sons to such a school to keep them away from the influence of drugs. Burma has been responsible for the world’s largest production of raw opium and today ranks second to Afghanistan in yearly volume. Opium is grown in the state of Shan in the northeast. We observed young boys with shaven heads relaxing in the school yard and having lunch in the dining room.

The Mingun Pagoda is the largest temple in Myanmar. Even from a distance, approaching the town by boat, one can see the massive ruins of the pagoda. Built more than two centuries ago during the reign of King Bodawpaya (1782-1819), the temple was damaged by an earthquake twenty years later. Nevertheless, the remains of the brick edifice, 164 feet high and 236 feet wide, are spectacular. From the top there is a magnificent view of the river.

Mingun also is home to the world’s largest working bell, which is three times as tall as a person. The Mingun Bell was cast in bronze in 1808, and once it was completed, King Bodawpaya had the master craftsman executed in order to stop him from making anything similar.

Built by King Bagyidaw in 1816, in memory of his favorite wife, is the impressive Hsinbyume Pagoda on the northern edge of Mingun. Its striking architecture is based on that of the Sulamani Pagoda on the mythical golden mountain of Meru, which is the center of the universe in Buddhist-Hindu cosmology. Seven terraces with undulating rails, representing the seven mountain ranges around Mount Meru, lead up the stupa, and along the way are niches with mythical monsters standing as guards.

Mingun is also known for its production of marionettes. The town market is lined with stalls stacked with marionettes of all sizes and characters. I bought a used one, simply because I liked the queen’s delicate features and her faded red costume embroidered with silver metallic thread. The saleswoman did not seem to mind parting with one of her stock characters; she was happy with the four dollars she received in return.

Lunch at a Chinese restaurant was one of our best meals. Soup with quail eggs and clear rice noodles in broth became my favorite throughout the trip. Sweet and sour fish and seafood with mushrooms were among the dishes, which were served on a rotating tray.

Following lunch we visited a gold leaf workshop, which was easy to identify by the rhythm of hammers beating gold into wafer-thin sheets. Two ounces of gold bullion is first stretched into a ribbon ¾ of an inch wide and 20 feet long. Then it is cut into pieces of equal length, which are separated by paper made from bamboo. 200 pieces of wrapped gold make one unit. Each unit ultimately yields 720 flakes through repeated hammering and wrapping. The workers use a 6 pound hammer in stages of 30 minutes each. The final stage produces gold leaves, which are cut into squares and pasted onto paper made from hay, ready for packing and shipping. In addition to its extensive use in sacred places, gold leaf is used in traditional medicine, as well as in make-up for fair skin.

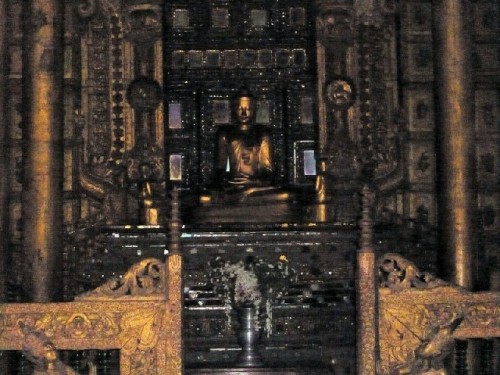

Visiting the Mahamuni Pagoda, one of the country’s most sacred temples, right after the gold leaf workshop increased my amazement many times over. In the center of the glittering pagoda sat the Mahamuni Buddha, totally covered in gold leaf by pilgrims, so that some parts of the body were hardly recognizable. In places the layer of gold on this ancient statue is twelve inches thick. Every morning at four, a ceremony is held, during which monks wash the face of the statue. Also in the pagoda are six bronze Khmer figures, which are 800 years old and were originally enshrined at Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Brought to Thailand as war trophies, they were later donated to Burma in celebration of its victory over Britain. Three of these figures are lions, and two are temple guards who, according to folklore, can cure the ills of the faithful if certain parts of their bodies are rubbed. The sixth figure is a three-headed elephant, the mount of the Hindu god Indra.

My last activity in Mandalay was walking on the world’s longest footbridge. I enjoyed the peaceful walk, viewing emerald fields alternating with fishing boats and traps on the tranquil waters that stretched on either side of me — an idyllic beauty etched in my memory.

The legendary “golden land” is still the Myanmar of today. Long cut off from the world, it is one of the most exotic countries I have visited. I enjoyed exploring and experiencing the mystical charms of Myanmar’s archeological sites, glittering pagodas and wealth of cultures, not to mention its tropical natural beauty and, most of all, its gracious and hospitable people.