Dali Museum in St. Petersburgh, Florida

Celebrating 100 Years of Surrealism

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 17, 2024

Sited on the marina/ waterfront of

The museum’s collection includes 96 oil paintings, over 100 watercolors and drawings, 1,300 graphics, photographs, sculptures, and objets d’art, plus an extensive archival library. It represents the acquisitions of Reynolds and Eleanor Morse. In 1942 they were inspired by a Dali retrospective at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Over 40 years they became the primary patrons and friends of Dali and his diminutive wife/ manager, muse Gala.

With the exception of the Dalí Theater-Museum, created by the artist in his hometown of Figueres in

Initially, the Morses displayed the work in their

The refrain “Won’t get fooled again” by the Who resonated subliminally as we entered the lobby, a vast gift shop. The glut of souvenirs and commercial merch, including “melting clocks,” reinforced misgivings about the integrity of the artist. Dali is noted for flamboyant persona, performances, and publicity seeking stunts.

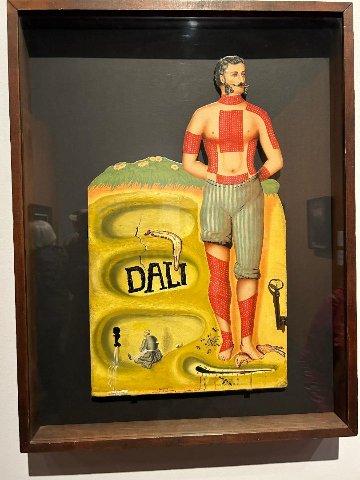

The lobby also includes a vintage automobile with a chauffeur wearing the helmet of a deep sea diver. It evokes a signature work “Rainy Taxi or Mannequin Rotting in a Taxi Cab” 1936. It recreates his contribution to a landmark surrealist group show in

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol, (1904-1989) was born in

Dalí’s older brother, who had also been named

His talent for painting developed early but lacked a prodigy’s skill and sophistication of his eventual friend Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

Through April 28, the

As a former Bostonian, this special exhibition was a matter of déjà vu all over again. For me what was overly familiar is undoubtedly thrilling for Floridians. The MFA was remarkably generous in lending a number of iconic works. The juvenilia of Dali shrinks by comparison. There is barely a glimmer of the genius which unfolded after 1926 and his move to

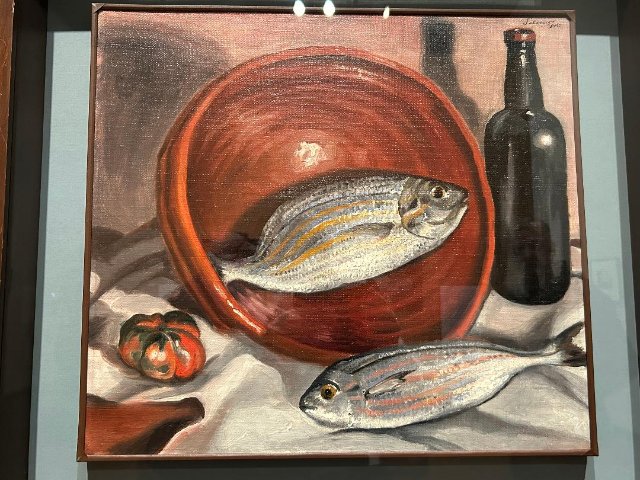

Dali’s early efforts at landscape feature thick paint and broken color in the impressionist manner. The juxtaposition of masterpieces by Monet, and a Pont-Aven work by Paul Gauguin, beg for comparison. There is an intriguing, stylized view of the Dali family village “Cadaques” (1923). The features of the peasant figures are abstracted. His experimentation at this time was eclectic indicating a range of influences including futurism.

There is a small, brooding head of a man, by nature very Catalan and Gypsy like, that is juxtaposed with the MFA’s masterful self portrait by Paul Cezanne.

The most striking and apt comparison conflates a Dali nude with Matisse’s 1903 academic nude study “Carmelina.” When the great modernist work was first acquired it was considered so controversial that a trustee resigned stating that the museum was no longer a safe place to bring his wife and daughters. That squashed the museum’s interest in modern art until Perry Rathbone, in the 1950s, made a few daring acquisitions.

The term ‘sur-realism’ had been coined by the poet Guillaume Appolinaire (1880-1918) in a review of the ballet Parade. Choreographed by Leonide Massine, with music by Erik Satie and a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau the ballet was created for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. It premiered May 18, 1917, with costumes and sets designed by Picasso. The ballet was said to have put cubism on stage and played a role in its public perception.

The young Dali was a quick study but the martinet Breton was a strict gate keeper. The breakthrough occurred when Dali, and fellow Spaniard, Luis Bunel, collaborated to make the film “Un Chien d’Andalou” in 1929. The surrealist masterpiece, a short, silent film, ran for eight months.

Dali’s luck changed when, in 1929, he met and later married (1934) Elena Ivanovna Diakonova (1894-1982) who was known as Gala. From 1917 to 1929 she had been married to the poet Paul Eluard (1895-1952). For a time, they lived with and formed a ménage a trois with the German artist, Max Ernst (1891-1976). He was later married to Peggy Guggenheim (1942-1946). Gala had many affairs throughout her life including boy toys in her 80’s. Her libido exceeded that of her voyeuristic husband.

Initially when Dali visited family in

Gala was brilliant in promoting Dali, including stunts in

There was little income until the steady patronage of the Morses. It’s easy to see why. I sat through a You Tube chronology of 904 paintings the majority of which were second rate. There were great works and inspired moments but, in all phases of the work, Dali is an artist who must be strictly curated.

His personal life and right wing political views were rather outré. He supported Franco in

Paco Barragan has written that “In 1948, Dalí returns to

When fame and money rolled in it was tits to the wind. He would do anything for money including signing reams of blank paper. The scam was that lithographed images would be added later. This opened the floodgates to endless fakes and forgeries.

It took vast stacks of cash to keep Dali and Gala in the style and luxury that helped to create and market their product and brand. They lived in luxury hotels and owned a modest home in

This was the Dali of the signature long, thin moustache and bulging eyeballs mugging for whatever camera and media was available. He hung out with the glitterati including Alice Cooper and Warhol superstar Ultra Violet. In later years Gala was ever less at his side.

With the deft finesse and tutelage of Gala, Dali became astute to the concept of selling the sizzle rather than the steak. It created a path for the artist as celebrity and entrepreneur. That was embraced by Warhol, Jeff Koons, Damien Hurst and others. They were all in debt to the master magician and prankster Marcel Duchamp.

Cut off from the avant-garde of

The

In the spirit of Duchamp and Dada, Dali made a few interesting objects including the seminal “Lobster Telephone,” 1936, a commission from the poet and collector Edward Frank Willis James (1907-1984). He sponsored Dali for the whole of 1938 and his collection of paintings and art objects subsequently came to be accepted as one of the finest collections of surrealist work in private hands. He also provided practical help, supporting Dalí for about two years.

They collaborated on the “Mae West Sofas” and “Lobster Telephones,” which James had installed in his private home near West Dean House. Of which Dali remarked “I do not understand why, when I asked for grilled lobster in a restaurant, I am never served a cooked telephone.” A white plaster cast of the lobster phone is included in the museum’s collection.

Another object entails several elements. There is the polychromed bust of a woman with ants swarming over her. On her head is an inkwell featuring the figures from Jean-Francois Millet’s painting The Angelus (1857–59) which is embedded in a loaf of bread. Her necklace is a strip of repeating images from a zoetrope, a precinematic toy that provides the illusion of movement as it rotates.

One of the most riveting works in the collection is a small, meticulous rendering of a “Basket of Bread,” 1926. Completed at the end of formal training it attests to representational skill that would manifest in his work. As a teenager, I recall being stunned by the bread in his life-sized painting, “Christ’s Last Supper,” 1955, at the National Gallery.

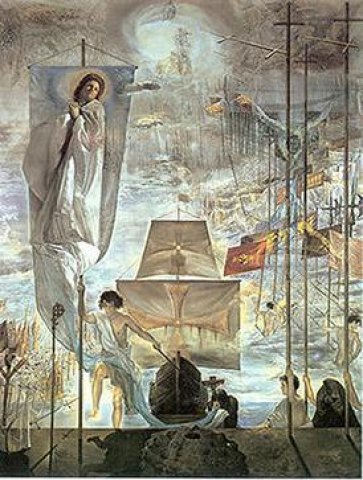

That ability to paint like Vermeer was the ace in the hole of Dali’s career. Now and then he would serve up a showstopper. Like the museum’s epic scaled, gob smacking “The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus” which took two years to complete in 1958-1959. It was commissioned for the conservative collector Huntington Hartford’s since shuttered Museum Gallery of Modern Art at

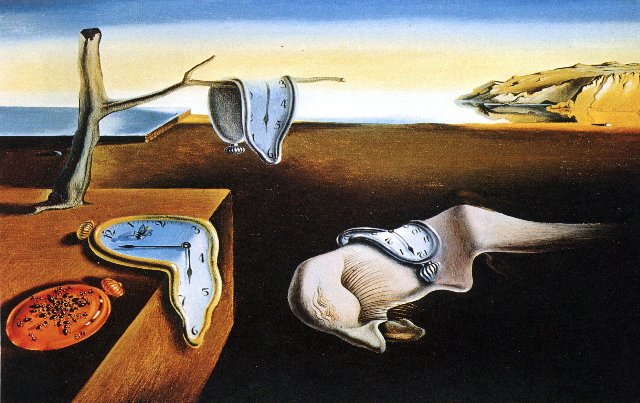

Arguably, his best known work and masterpiece is “The Persistence of Memory” 1931. It was included in his first

In 1954 Dali created the museum’s “The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory.” In this version, according to Wikipedia “The landscape from the original work has been flooded with water. Disintegration depicts what is occurring both above and below the water’s surface. The landscape of Cadaqués is now hovering above the water. The plane and block from the original is now divided into brick-like shapes that float in relation to each other, with nothing binding them. These represent the breakdown of matter into atoms, a revelation in the age of quantum mechanics.

”Behind the bricks, the horns receding into the distance symbolize atomic missiles, highlighting that despite cosmic order, humanity could bring about its own destruction. The dead olive tree from which the soft watch hangs has also begun to break apart. The hands of the watches float above their dials, with several conical objects floating in parallel formations encircling the watches. A fourth melting watch has been added. The distorted human visage from the original painting is beginning to morph into another of the strange fish floating above it. To Dalí, however, the fish was a symbol of life.

“Dalí had been greatly interested in nuclear physics since the first atomic bomb explosions of July 1945, and described the atom as his ‘favorite food for thought’. Recognizing that matter was made up of atoms which did not touch each other, he sought to replicate this in his art at the time, with items suspended and not interacting with each other, such as in The Madonna of Port Lligat. To Dalí, this image was symbolic of the new physics—the quantum world which exists as both particles and waves. The imagery of the original Persistence of Memory can be read as a representation of Einstein’s theory of relativity (although Dalí himself denied the connection to the theory), symbolizing the relativity of time and space. In this new work, quantum mechanics is symbolized by ‘digitizing’ the old image.”

Why didn’t I think of that? My initial take of the reworked “Persistence” was Dali’s interest in the emergence of Op Art.

That said; why not leave the last word to Gertrude Stein? “The surrealists still see things as everyone sees them, but the vision is that of everyone else.”