Route of the Maya: Part One

El Salvador

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 09, 2016

This year’s choice for my February get-away was Central America. The Route of the Maya itinerary by Overseas Adventure Travel offered an opportunity to see the archeological, cultural, and natural wonders of El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and Nicaragua. I flew from Boston to San Salvador via Dallas/Fort Worth – a total of seven hours flight time plus a couple of hours for the connection – and landed at my destination around 7 pm, adjusting my watch by one hour behind Boston time. El Salvador does not require a visa for American citizens, but collects a $10 fee for entry into the country.

Welcomed with a big smile by our trip leader Ivania, I, along with one other member of our group of twelve quickly set out on a dimly lit road along El Salvador’s tropical coast to Pacific Paradise, a seaside hotel south of the capital city. Feeling too tired to appreciate my surroundings; I looked forward to the next morning’s exploration before starting the pre-trip itinerary to Colonial Suchitoto and the Flower Route.

In the morning the splendor of our surroundings emerged, as tall palms reflected in the shimmering waters of the hotel’s swimming pool. Following breakfast we left for a boat ride along the Costa del Sol, lined with beaches, fishing villages, and mangroves enjoyed by many seabirds. At a distance, clouds hovering around the crater of a volcanic mountain added to the beauty of the setting. The boat ride ended with a refreshing coconut juice in the shell, purchased with US currency, which is accepted throughout El Salvador.

Later on we traveled north overland to colonial Suchitoto, stopping at quaint towns along the way. The first was Olocuilta, a town known for its rice flour pupusas, which are like tortillas with a filling. Introduced by the Spaniards, pupusas were originally made of corn. Pupuserías, where they are made, offer a choice of fillings for around 75 cents apiece. This region, near the scenic Crater Lake Ilopango, holds an annual Pupusa Celebration on the 2nd of November.

A native of Olocuilta, our local guide hosted us for lunch at the local restaurant he runs with his wife, who was the cook. A descendant of a Spanish family, he lived on the inherited property, where he ran a boutique hotel and ran a gift shop adjacent to the restaurant. I purchased my first souvenir item here – a necklace fashioned out of pieces of coconut shell.

Then we visited a family of basket-makers at their modest home, where everyone worked in the garden on some aspect of making a large basket, such as splitting the bamboo, weaving the base or the side, or finishing the rim. Used for carrying goods on the head, baskets needed much practice to balance with no hands, as I quickly found out.

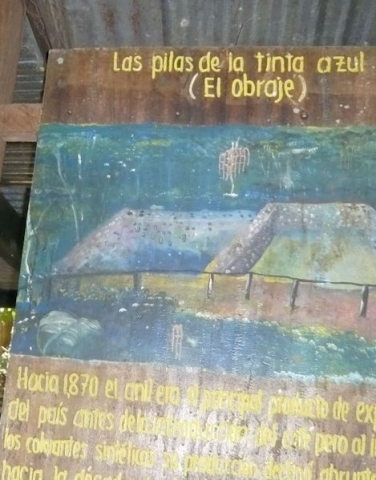

Arriving in Suchitoto in the mid-afternoon and following check-in at the hotel Los Almendros, we toured the colonial city on foot. Our stroll coincided with the end of the school day, when students in uniform animated the city’s charming cobbled streets. A highlight of our tour was an outdoor exhibition of photographs of paintings – many on loan from the Prado Museum in Madrid – for Suchitoto’s 26th annual Alejandro Cotto International Festival of Art and Culture (February 6-28), named after the musician who founded it. Other stops were the main square, where Santa Lucía Church is located, and an indigo craft shop, where I purchased a yellow-and-blue shirt dyed with leaves harvested from an almond tree and the xiquilite plant, used by the Maya to extract dye.

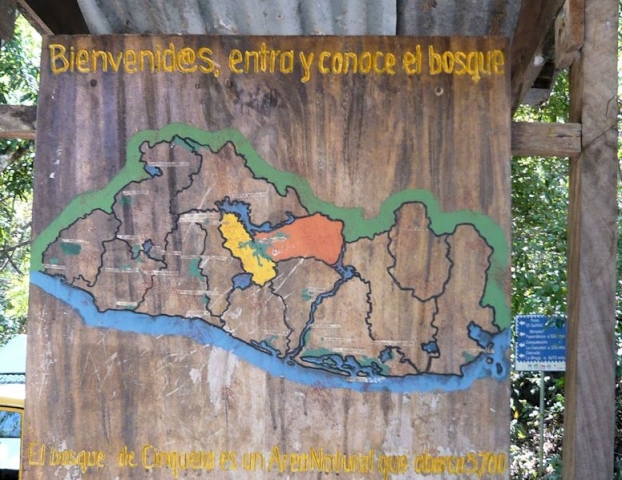

The village of Cinquera, 18 km south of Suchitoto, was the next day’s destination. Traveling along Suchito Lake, where we caught glimpses of volcanic white ash billowing in the distance, we first arrived at the Ecological Park of Cinquera. Met by a park ranger, we hiked some of the winding trails of the rain forest preserve, as the ranger pointed out the ancient walls of pools the Maya used to soak the xiquilite plant, their shelters and cooking facilities. We ended the hike around a pool of water fed by a small waterfall where locals gathered to cool off and enjoy a picnic.

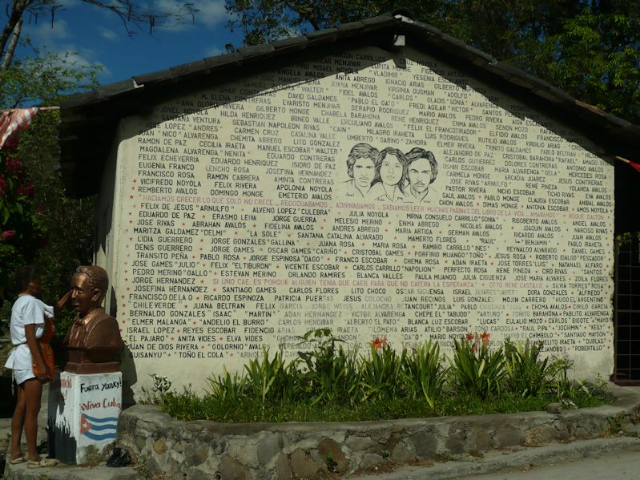

Continuing on to Cinquera took a while due to road construction. Our local guide, Raphael, used the time to tell us about El Salvador’s civil war (1980-1992) and his personal involvement as a fighter after joining the guerrilla forces at the age of 16. According to his account, fourteen wealthy families owned all the land in the country. Others worked as campesinos (farm workers) six days a week. On Sundays they had to choose between going to church and working on fields rented to them. Although the rented lands were of poor quality, they still had to give their best crops to the land owners. Campesinos were very poor; their children had no clothes. They began organizing in 1978 against the land owners; the government interfered by sending military personnel and police to destroy the guerrillas. Civil war ruined the country; people began coming back in 1991 and started rebuilding from the ashes.

Cinquera was a stronghold of guerrilla resistance. Everyone who stayed in the town supported the revolution in some way as a cook, nurse, or the like. Evidence of the town’s past can still be seen in the bomb and bullet damage to several of its buildings. The tail of a downed military helicopter is on display in the town square. Wall murals honor the leaders of the revolution; portraits of war heroes along with the names of people who have disappeared arrest your attention on building facades. History and nature are assets for tourism, and attracted 14,400 people in 2015. Happy to bolster the economy, we all had the typical local dish for lunch – chicken soup, consisting of gizzards in broth served with a quarter of a chicken on the side.

On the way back to Suchitoto, I opted to learn more about the indigo industry by visiting a workshop. After 300 years of thriving, the industry declined because of the invention of synthetic fabrics. The artist has successfully revived it by growing the xiquilite plant in her own garden. It takes 1500 pounds of leaves to produce three pounds of powder. The leaves are moved from one bin to another as they are washed, boiled, and then stirred to infuse oxygen and help fermentation. When the blue sediment settles, it is dried out, and then pounded into powder. I created a design on a piece of cloth by wrapping rubber bands around areas that I wanted to stay white, before dipping the cloth into a dye bath to obtain a light blue color. The number of times the cloth is dipped determines the intensity of the color. Finally the rubber bands came off, revealing the design.

The last activity of this long day was an enjoyable concert by an all-woman chamber orchestra playing works by women composers. Part of the International Festival of Art and Culture the program opened with the national and city anthems, followed by official greetings and speeches. The twelve instrumentalists of the chamber group were all members of the El Salvador Symphony Orchestra; a mezzo soprano and a soprano were featured throughout the program.

The next morning we left for Ataco, stopping on the way at the Cihuatán Archeological Park, the site of the ancient capital city of a post-Mayan, pre-Hispanic civilization dating from 900 to 1000 AD. The vast city, destroyed by a fire set by unknown invaders, was discovered in 1925 and is partially open to visitors, as many parts are yet to be excavated. Following a trail, we saw the ball courts, the ceremonial center with the main pyramid, and various small temples, all enclosed by a defensive wall, in addition to many ceiba trees. In Mayan belief the very tall ceiba tree, with its large branchless trunk culminating in a huge, spreading canopy, symbolizes a central world tree, which connects the underworld, the terrestrial realm, and the skies.

The builders of ancient Cihuatán created monumental structures of stone, using stucco for walls and for binding lime plaster made from seashells hauled from the Pacific coast. We went up the main pyramid via a modern stairway, built with funds donated by the US Embassy, which also participates in the Cihuatán Conservation Project, supported by the US Ambassadors Fund. The pyramid’s summit offers spectacular views of the valley over which the city once reigned. The eastern view is dominated by the Guazapa volcano, whose silhouette, according to local tradition, resembles a woman reclining on her back.

The ball courts gave us a glimpse of the Maya ball game, played between two teams on a long field flanked by inclined walls, so built in order to bounce the ball up at an angle. Players wore thick protectors at the waist to minimize the impact of the heavy solid-rubber ball, which could not be kicked or thrown by hand, but was instead bounced off heavily padded elbows and knees. When a ball entered the wide space at either end of the field, the team on the other side scored a point. Exterior stairs to the flanking walls allowed access for spectators.

Continuing on to Ataco, we headed west, stopping along the way at Nahuizalco and Juayua, each distinguished by a unique white church overlooking a park in the town center. Ataco is a mountain town known for its weavers, woodcraft, and murals. We visited a painting studio shared by two brothers, strolled to admire fancifully painted building facades, and had dinner at the Misión de Ángeles hotel, our home for the night up on a hill. A dessert consisting of the local specialty, caramelized sweet potato, further sweetened our day.

In the morning we visited the El Carmen Coffee Resort outside Ataco on the Flower Route, so named because of all the flowering coffee plants in the region. We walked among the plants and learned about the journey of coffee from harvest to export. Coffee beans are picked by hand and washed to determine quality by size and weight, and to remove their sticky coating, then spread and raked for quicker drying. A filtering machine removes the parchment-like skin around the beans before they are roasted. The duration of roasting determines the strength of the coffee beans, which are then powdered and bagged for shipping. At the end of our visit we enjoyed a cup of filtered coffee in the garden.

Cerro Verde (Green Mountain) National Park provided the day’s spectacle. At an altitude of some 6600 feet, this very large park includes three imposing volcanoes; Santa Ana sits in the background of Cerro Verde, which is in the center, with Izalco to the far left. We were able to see Izalco at close range from a lookout point. Before entering a dormant period in 1966, Izalco was known as the “lighthouse of the Pacific” due to its 160 years of continuous eruptions. Meanwhile the highly arable land has been used to produce coffee, cacao, and sugar cane, all high income producers for El Salvador. With the guidance of a park ranger, we walked about a mile through the park, enjoying its abundance of trees and birds.

Our nature tour continued on to Boquerón Park, which is located on top of the San Salvador Volcano at 5905 feet. A huge crater, 5 km in diameter, is the main attraction of the park, with short hiking trails up the side and along the rim. Within the main crater is a smaller one, named “Boqueroncito” (Little Boquerón). The park is home to many species of plants and wildlife.

Satiated by nature and feeling ready for the urban bustle, we departed for San Salvador to meet the rest of our traveling companions and begin our main trip along the Route of the Maya.

(To be continued)