Colombia: Part One

Bogota

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 01, 2014

To start the main trip of our itinerary, Colombia’s Colonial Jewels and Coffee Triangle, we flew from La Paz to Bogota by way of Lima, Peru, as there are no direct flights between Bolivia and Colombia. Paulo, our trip leader, met us at the airport and assisted with the transfer to the Hotel de la Ópera, where we joined the other five members of our full group of twelve. The hotel is in La Candelaria, the historic heart of the capital city, which sits in the high plains of the Andes at an altitude of 8,660 feet. Distinguished by its Spanish colonial architecture, my hotel room opened onto a charming interior courtyard, which was covered with a glass dome and served as a dining area. Paulo delivered a box of chocolates to my room, wishing me “Happy Birthday.”

Shortly after arrival, we went on a walking tour of La Candelaria, the hub of cultural life for the city’s population of over eight million people. Strolling down narrow streets, we arrived at Plaza de Bolívar, a vast square bustling with people and pigeons, and a magnet for the city’s social life. The square is flanked on the eastern side by the 18th-century Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception; on the western side by City Hall, formerly the Liévano Palace; on the northern side by the Palace of Justice; and on the southern side by the Capitol building, where congress meets— each with a distinct architectural style. At the center of the plaza is a bronze statue of Simón Bolívar, the revolutionary leader who plotted independence from Spain in 1810 and became the country’s first president.

Catching glimpses of the Andes through the vistas of hilly streets, we rushed to the Botero Museum before closing time. Botero’s art and private collection exhibited at the museum exceeded my expectations, prompting me to write a separate article for BFA, which is posted in the Fine Art section.

The next morning we took the funicular to Montserrate, a 10,000-foot hill with the 17th-century Catholic Church of St. Mary at the summit, offering panoramic views of Bogota below. We walked the uphill path lined with the Stations of the Cross along the way to the church. This is a popular site for pilgrims, who climb the path on their knees during Lent. The Black Madonna in the chapel is a replica of the one in Catalonia. The walls are covered in plaques with carved inscriptions of gratitude and love left for the Madonna by visitors. Guadeloupe, a hill visible from Montserrate across the way, has a towering statue of the Virgin Mary at its summit.

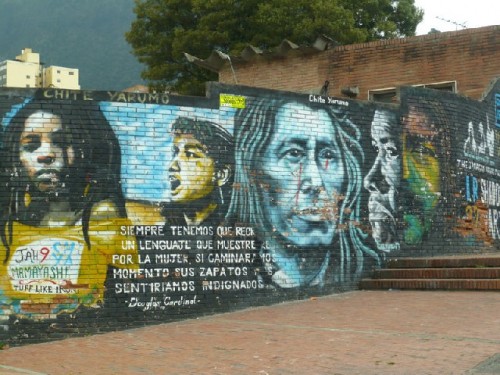

We returned to La Candelaria for lunch and then explored the different neighborhoods of the historic center on foot. In the 1990s, the mayor offered to reduce property taxes and utility bills, provided home owners maintained the colonial facades of their houses. As a result, many refurbished buildings, some displaying the work of muralists or graffiti artists, line the streets, which are enlivened by students at lunch time. Police with muzzled guard dogs were visible around a group of students, as preventing drugs and explosives are a high priority for the government to ensure public safety. Education in Colombia is free; the literacy rate is 98%. Due to the high number of students, schools operate in two shifts — morning and afternoon.

A highlight of the trip was immersion in the galleries of the Gold Museum, which houses the world’s biggest collection of pre-Hispanic gold artifacts. Of the 55,000 pieces, 6,000, including pottery, are on display, providing an introduction to the indigenous cultures of Colombia and Amerindian thought. The four galleries begin with displays of metal working to create objects, progress to the symbolic use of these objects, and end in an offering room, where the metal is returned to the earth, thus completing the cycle. Exhibits include mythical birds bringing light to the world in their beaks, figures with animal characteristics imparting the power of a jaguar or a puma, masks, ornaments, funerary objects, and a “Muisca raft” used for offerings. Accidentally found in 1969 by hunters, the raft is a 19.5-cm-long oval vessel, complete with a chieftain with headdress, earrings, and nose ring and flanked by other dignitaries.

El Son de los Grillos, a 400-year-old restaurant with intact original ceiling beams, was the location for our welcome dinner. Starting with an appetizer of fried manioc dipped in tomato sauce, dinner continued with potato soup from cilantro-flavored chicken broth, followed by sea bass, and ended with apple strudel for dessert.

On the way the next morning to the Salt Cathedral of Zipaquira in the mountains 40 kilometers north of Bogota, we stopped by the produce and flower markets. Among the fruit exotic for northerners were yellow dragon fruit and granadilla. Belonging to the pomegranate family, the latter looks like an orange with a hard shell and, when cracked open, reveals a soft whitish flesh with many seeds. It is eaten by scooping out the soft flesh with a spoon. The section designated for folk beliefs had aloe vera plants, sold to bring good luck when hung around the house; potions from the plant in small bottles were for use in bathtubs to help bring love.

At the meat market we watched a butcher chop up a pig, while its skin hung in the rafters to dry. A gutted pig, refilled with cooked rice mixed with meat and spices and sold by the plate, proved to be a popular item at the lunch counter. Eggs of all kinds and sizes in cardboard boxes filled a shop from floor to ceiling.

Flowers are big business in Colombia. They are brought to the market by the truckload. A vendor proudly mentioned to our local guide, Andrés, that she had educated three sons— a journalist, a psychologist, and an engineer — by selling flowers. When asked what her husband gave her on special occasions instead of flowers, she told us, beaming, that he serenaded her.

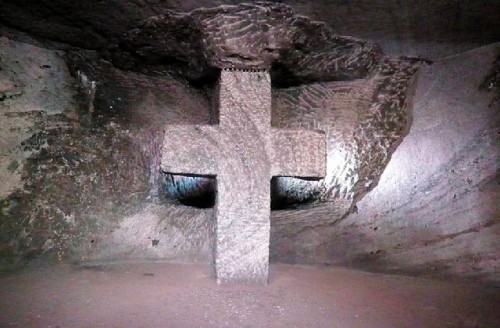

Back on the road, the Salt Cathedral of Zipaquira, which was offered as an optional tour, proved to be one of the highlights of the trip. Zipaquira is a 17th-century colonial town with a population of 120,000. Long before Christians came, it was inhabited by the Muisca Indians, who discovered the salt mine, formed 200,000,000 years ago by receding waters over the area. The Muisca used the salt as currency and traded it for gold, accumulating wealth.

This is the second of two cathedrals carved into the salt mine 600 feet underground. The original one, built in 1953, was a huge cavern within the mine, but became unstable over the years and had to be closed down. Therefore, a second cathedral was hewn out of the rock by salt miners at a safer location, following a competition for the architectural design. The second cathedral was inaugurated in December 1995; 90% of its statues and ornaments have been relocated from the first cathedral. The entrance plaza leads to the Salt Museum; pedestrian ways lead to the Great Ceremonial Plaza, surrounded by 40 wax palms, Colombia’s national tree.

The underground complex is entered through an archway featuring a stone relief of miners. This leads to low-lit tunnels lined with 14 small chapels, which depict symbolic semi-abstract versions of the Stations of the Cross. The cathedral itself is at the deepest point of the route in the largest gallery, with carvings and a salt altar. There are three naves; the central one has a 16 meter high cross which appears from a distance to be sculpted in rock, but is only an illusion. An active Roman Catholic Church, the cathedral attracts up to 3,000 people to its Sunday services in addition to hundreds of daily visitors. Its haunting illuminated chambers filled with piped in sounds of Gregorian chants left me with an indelible impression.

At lunch a local restaurant, Funzipa, introduced us to typical food of the Colombian highlands. The dishes, flavored with rock salt, included ajiaco, a soup made from chicken, sweet potato, and corn and served with sour cream and capers. This came with a side of arepa (corn cake filled with cheese), rice, and sliced avocado to be eaten with a spoon. For dessert we enjoyed cheese curd with caramel sauce made from raw brown sugar.

Riding back to Bogota, I was able to observe the city’s attempt at efficient traffic flow from the bus window, as there is no underground metro yet. Public buses with double cars, called the TransMilenio, travel on a dedicated separate lane; overpasses allow pedestrians to avoid busy streets, as cars do not stop to let them cross on the ground. Cars have color-coded odd or even numbered plates for the days of the week when they can be driven.

The city is divided into zones, starting with lower numbers for poorer areas and moving to higher numbers for affluent communities that pay higher taxes. The loss of tax revenue from low income zones is made up by those living in high-end neighborhoods, as the city derives 80% of its revenue from taxes. A toll booth separated the city from the affluent suburbs, where high rise apartments dotted the skyline against a backdrop of lush green hills.

Returning to Bolivar Square, we walked down to the Presidential Palace, which is heavily guarded. We had to have our bags checked before we could enter the street which the fenced-in palace faced. We were able to view the palace from the street, but not from the sidewalk along the fence.

Back at the hotel, the last activity of our day was a lecture by a local expert on Colombia’s recent history of dealing with guerrillas and drug cartels. In the 1960s, leftist guerrillas fought for ideals over money, while the government fought against the drug cartels. By the 1990s, the government, guerrillas, and drug lords were all fighting one another and people were being kidnapped. Rural communities growing coffee and flowers were caught between the drug lords and government forces. One pound of cocaine produced for 50 cents by cooking coca leaves with the addition of a solvent sold for $150 overseas. Drug conflict and corruption harmed the country’s infrastructure, health, and education.

The critical condition created by internal conflict received international attention. US AID, the EU, and NGOs all tried to help the government to develop. People who wished to were allowed to destroy coca crops and refertilize the land. To escape the conflict, many farmers moved to the cities. Paramilitary forces gave up their arms to the government; the illegal army disappeared and drug king Pablo Escobar was killed. The legalization of drugs is on the table as a possible solution. The current conflict is between the guerrillas and the government. The army is present everywhere; people now feel safe and participate in the political process.

Having gained a richer understanding of Colombia’s recent history, we looked forward to the continuation of our trip to Medellin the next morning.

(To be continued)