Berta Walker Legendary Provincetown Gallerist

Then and Now

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 31, 2025

Berta Walker Gallery, Then and Now

The Berta Walker Gallery, through its inventory and exhibition program, represents the full spectrum of Provincetown’s artists. She shows works by the pioneering generation that founded the Provincetown Art Association and Museum as well as leading current artists. That reflects the deep roots of the Walker family. It’s that heritage that inspired founding the gallery 36 years ago.

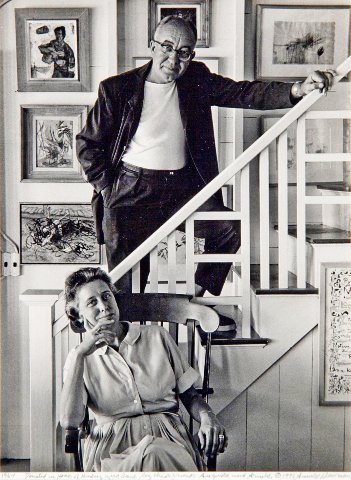

Her grandparents, Harvey Gaul, musician, and Harriet Avery Gaul, writer, from Pittsburgh, discovered Provincetown in 1915. Their daughter, Ione, an artist, married Hudson Walker and they started bringing their three daughters, Berta, her twin Louise, and older sister Hatty to Provincetown in 1943. Ione and Hudson ran a gallery in Manhattan from 1938–40. This string of events finally led to the important contemporary gallery in Provincetown, the Berta Walker Gallery.

In October 2024, we met at Berta’s gallery as she was wrapping up the installation of a new exhibition,

Charles Giuliano So this is the 35th (2024) year of Berta Walker Gallery.

Berta Walker (laughing) Oh, I’m being interviewed? How many years has it been? I knew you before I opened the gallery. That’s how far back we go. How did I come to open a Gallery in Provincetown?

You may be old enough to know the saying “I got my job through the New York Times.” I got my job through the Fine Arts Work Center. For years, while living and working in New York City at the Whitney Museum, Marisa del Re, and Graham Modern Galleries, I spent time in Provincetown, where I’d spent summers since 1943. Along the way, I got interested in the wellbeing of FAWC and launched townwide fundraising events, and then annual events in New York and Boston. Later, after five years as founding director of Graham Modern Gallery, I got the idea I needed a little R & R from New York. I left Graham and moved to Provincetown for the summer, where, as then Chairman of the Board of FAWC, I had lots to do. As you know, I’ve been coming here since I was two and have been here most every summer since then. That’s why I know all the people you have been writing about.

(The Fine Arts Work Center [FAWC] was founded in 1968 by a group of artists, writers, and patrons, including Stanley Kunitz, Robert Motherwell, Fritz and Jeanne Bultman, Josephine and Salvatore Del Deo, Alan Dugan, Jim Forsberg, Phil and Barbara Malicoat, Myron Stout, Jack Tworkov, Hudson and Ione Walker. The founders envisioned a place in Provincetown, the country’s most enduring artists’ community, where artists and writers could live and work together in the early stages of their creative development. They believed that the freedom to pursue creative work within a community of peers is the best catalyst for artistic growth.)

Shortly after I moved here in the summer of 1989, we had an emergency at FAWC and we had to let the director go. The board president said, “You know the Work Center well, so why don’t you become the acting director?” My R & R became a relocation to Provincetown! At the end of that year, I opened the gallery. There was a space available downtown and a friend said, “You have to open a gallery.” I said, “No way,” but his response was, “Of course you can.” It was 1990, and I opened across the street from the Post Office.

I rented that space for two years, but the landlord kept increasing the rent. You can’t do that to a gallery and have it survive. In those days I found I could buy a building and the monthly mortgage payments were lots less than the rent. So, that’s how I landed here.

(Early on, when property was still affordable, Berta acquired the building which houses her gallery. Such a move is no longer possible as real estate values have soared. The changing demographics have greatly impacted the creative community.)

BW It’s a condo and can be a combo living/business space. And behind it is another apartment that I now regret not having purchased. At the time I didn’t have the extra revenue. It’s just fortunate that this property came on the market and could be renovated as a gallery space.

(She greets Stephanie Vevers and they discuss her mother, the artist Elspeth Halvorsen.)

I always think of Elspeth, whom I’ve shown practically since the gallery opened, as such a gutsy woman. A good example is when Long Point started in 1977, instead of kicking and screaming about not being included, Elspeth started her own cooperative gallery, Rising Tide, in the same building. Her husband, Tony Vevers, was part of Long Point Gallery.

I remember when they started Long Point, I was in New York working at the Whitney. Budd Hopkins called me and said, “We’re starting a co-op gallery and you should come and run it for us.” I had a full-time job and couldn’t leave it for Provincetown. All these years later, I got to meet Budd’s daughter, Grace, who is now director of this gallery. Today there is no Berta Walker Gallery without Grace Hopkins.

CG When did you step back?

BW I haven’t stepped back. Though “this antique” is not in the gallery as much as previously, I do all the curating, advertising, and PR from home. I do the initiating, plotting and planning.

CG I wrongly assumed that you took over the Hudson Walker Gallery. (As Hudson Walker told Dorothy Seckler, “I went back to Minneapolis and the family's lumber and real estate business until ’36, when I was married, and my wife, Ione Gaul, and I opened a gallery in New York at 38 East 57th Street, which we continued until 1940.”)

BW There is the Hudson Walker Gallery here at the Fine Arts Work Center, named for my father, who was so supportive of the Center. Even as he was dying, he worried about the FAWC. I helped him to create a codicil to his will leaving a major Hartley painting, Give Us This Day to the Center. It sold for $1,000,000, creating the initial endowment for FAWC. And yes, my parents did open the first Walker Gallery in New York City. Mom was an artist, In fact, there’s a small piece by her in this show we’re installing that a lot of people seem to like.

I always say that the Berta Walker Gallery represents the history of American art as seen through the eyes of Provincetown. My gallery is very involved with artists who have connected in Provincetown. Many live in New York and many other places, but all are very much a part of the Provincetown Art colony.

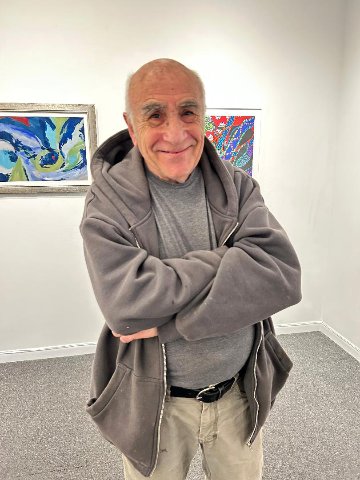

This summer, for example, five of our artists are involved in museum shows: Carmen Cicero, New York and Provincetown, Joe Diggs, upper Cape and Provincetown, Laura Shabott full-time Provincetown, Donald Beall, full-time Provincetown, and Varujan Boghosian (1926-2020). Our artists range in style from figurative expressionist, abstract expressionist, folk/“outsider” or, “wildly mixed,” originally known through Phyllis Kind’s words as “Chicago Hairy Who,” i.e. Great Original Fantasy. Perhaps I should coin the phrase GOF art, if unusual talented originals must be categorized. From my perspective, all my artists are great originals, talented and willing to communicate.

As a child, I remember Ione saying, “I can’t be in the studio except when you’re in school.” It was definitely hard being an artist and a mother. Still is! I guess her struggles as an artist have guided me in working with artists. I have always shown many women. But actually, I didn’t realize it until I got an award for support for women in the arts. It was the height of the Guerilla Girls and I was apparently one of the few galleries featuring women. I always thought I was just presenting talented artists who happened to be women: Susan Crile, Selina Trieff, Joan Thorne, Marjorie Strider, Nancy Fried.

I remember when I was in high school helping Sue Fuller (my mother’s close friend) create a “string installation” throughout the entire Bertha Schaeffer gallery around 1957. Back then, I was 6-feet tall and useful in such undertakings. It was very exciting. In fact, thinking back, Sue was quite the original, “a woman” creating installation art many years before it was so recognized. A few years later, after returning from a CAA Conference (College Art Association) Sue said to me, “I’ve just learned why I’m having a hard time being respected as an artist.” I said, “Why, Sue?” she looked at me with a huge grin, “I’m a woman!” Today, Sue is quite highly respected and sought after, particularly in Europe.

Back to your question about the Hudson Walker Gallery. My parents ran it in New York from 1938 to 1940. The war started, and they closed it and never again had a gallery. Dad was very much an anchor administrator of the arts. He was involved with MoMA and was the founding president of Artists Equity. I believe it was the only time AE ever had a non-artist as its head. It was started by the artists of the WPA in New York. They represented Marsden Hartley, among others, and later acquired a number of his works from the Steiglitz Estate through Georgia O’Keeffe.

CG What was his source of income?

BW He was a jeweler. Why Dad ended up as a jeweler was because he liked color and gems. His partner was the diamond expert; Dad ran the business. It turns out I love color, too. Both Dad, during his lifetime, and I today, respond to the “messages of color” if you will. What I’ve come to learn is that colors reflect various aspects of our spirit energy. Our body energy levels are referred to as chakras: Red anchors you, while blue is the voice. Green, our heart chakra, represents love. That may sound foreign, but I learned about chakras and discovered my dad and I respond a lot alike with parallel intuition. In fact, in this show we’re opening tomorrow, Renewal Through Color, we’re featuring the color blue. Why? Blue is the color of our voice chakra. This show is dedicated to the strength and voice of Kamala (Harris).

Dad was known as the silent mayor of the arts here in Provincetown and in New York. Taking a break from college for a year, I went to work as a runner for his jewelry store. It meant that I was taking diamonds from the shop to the diamond district on 42nd Street. I remember once when a dealer dropped his diamonds down on a grid in the street, there was chaos as they recovered them. (laughing) That was my introduction to being a runner. They step outside to look at the diamonds in the sun and he dropped them. I’ll never forget it.

My parents came here because my mother’s parents came here in 1915. My grandmother was a writer who had the pen name of Avery Gaul because she was a woman. My grandparents came from Pittsburgh. My grandfather was a composer and musician and he traveled the globe finding and transcribing “Traditional Music” from many cultures. (Known today are such spirituals as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” also one of the traditional Easter Alleluias.) I was hearing so much about art and theater from those days through my grandparents who participated actively with such as Mary Heaton Vorse and Harry Kemp, both of whom I knew as a child. They fed me in such a way that I was destined to come back to Provincetown years later and launch a gallery focused on the history of American Art as seen through the eyes of Provincetown. I feel it connects me back to the early days of the art colony.

My grandmother was a close friend of Mary Heaton Vorse. She was very important and her house (466 Commercial Street) has been restored lovingly by Ken Falk. She was a writer and went overseas as a correspondent during WWI. It was in her boathouse that the first plays of the Provincetown Theater (Provincetown Players) were launched.

(Mary Heaton Vorse [October 11, 1874–June 14, 1966] was an American journalist and novelist. She established her reputation reporting the labor protests of a largely female and immigrant workforce in the east-coast textile industry. Her later fiction drew on this material profiling the social and domestic struggles of working women. Unwilling to be a disinterested observer, she participated in labor and civil protests, and was for a period the subject of regular U.S. Justice Department surveillance.

In 1915, Vorse helped stage the first performance of a repertoire that included Ida Rauh, Susan Glaspell, George Cram Cook, John Reed, Hutchins Hapgood, and Eugene O'Neill. Once established, the Provincetown Players moved to Greenwich Village in November 1918, opening their own Provincetown Playhouse with O'Neill's one-act play Where the Cross Is Made.)

CG When your father closed the gallery in 1940, he helped to place the artists he represented with other galleries. Can you discuss that?

BW It was so long ago that I can’t remember. I can’t remember who he placed where, but I can tell you a story about my father and Marsden Hartley. He was with Alfred Stieglitz at the time, and Dad loved his work. Hartley and Stieglitz were not getting along, so he joined my father’s gallery. I will always remember Dad noting how difficult it was to sell the work, and was always worried about Hartley and his health. Then with a big grin he’d describe making a trade of a Hartley for a full set of teeth and Hartley could eat again!

CG Did he collect?

BW Yes. When O’Keeffe (the wife and heir of Stieglitz) was selling from the estate, Dad offered to buy all of the Hartleys for $5,000. He got a call from a man I can’t remember and he told my father, “I have talked to O’Keeffe and she will sell me her Hartleys for $5,000. What do you think?” Dad said, “I just put a check in the mail for the work. I’m not going to let O’Keeffe make us compete. Why don’t we just take our money ($5,000) and split the work?” There were two stacks of paintings and each took turns selecting.

CG What did he end up with?

BW That I don’t know, but a lot. More than a hundred works, most of which are now in the museum of the University of Minnesota. He was the founding curator when he was there and thus left most his collection to the university gallery.

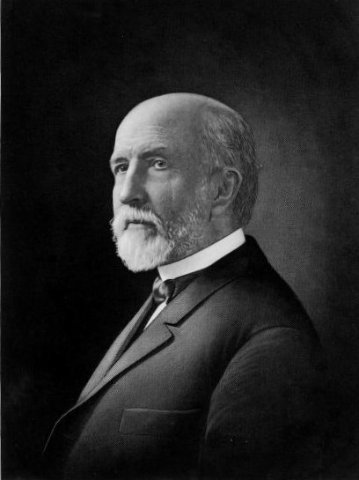

- CG. Your father’s grandfather was T.B. Walker, who founded the Walker Art Center?

BW Yes. As a young man Thomas Barlow Walker was in the lumber world. He and a friend took a wagon of supplies to sell to loggers in California. One day the wagon disappeared. Whoever his partner was took it and disappeared. There he was abandoned, but he didn’t indulge in “poor me” as so many do. When you get knocked out you stay down or get back up. So, he said, guess I’ll learn to cut trees. One thing led to another and he did very well. He invested in timber. He collected a lot of art and opened his home to the public in Minneapolis. It was the same year that the Met was founded.

CG That was 1870.

(In 1879, lumber baron T. B. Walker invited the public into his downtown Minneapolis home to view his art collection. In 1916, Walker bought land in Lowry Hill that he offered to the city of Minneapolis as space for a public library and art museum. After five years of futile negotiation, Walker resolved to build his own museum. Construction began in 1925, and the Walker Art Gallery opened in 1927. After 1935, Walker’s grandchildren, [except Hudson, who was in New York] and Louise Walker McCannel, ran the gallery until the Minnesota Arts Council took charge in 1939.)

The Walker Art Center was T.B. Walker’s collection.

CG What was in the collection?

BW A very mixed bag. Dad left most of his art estate to the University of Minnesota. They own the largest single collection of works by Marsden Hartley.

CG Did you inherit any of the work?

BW A few things, but the bulk of Dad’s collection went to the University Gallery. The first work I owned was a painting Marsden Hartley gave me and my twin sister when we were born. He gave my older sister a huge silverpoint when she was born.

(Disruption to greet and converse with visiting artists Paul Bowen and Bert Yarborough.)

CG Can you give me a few more minutes. Please discuss the historical collection of the gallery.

BW I like to juxtapose past and present. A Grace Hopkins work with one by Hans Hofmann, for example, Bert Yarborough with Lazzell, Sky Power with Knaths, or Hartley with Resika. The community is so vibrant today, and even though I didn’t know the early artists, my grandparents did. They came when artists arrived in Provincetown after war broke out in Europe. Many of them, like Oliver Chaffee (1881–1944), who is in this show. He was an early master who came to Provincetown then connected and studied with Charles W. Hawthorne (1872–1930). He then invited Hawthorne to join him in France. So, it’s really through Chaffee and Hawthorne that so many of the expatriate artists landed in Provincetown. A lot of them were women, like Ethel Mars (1876–1959) and Agnes Weinrich (1873–1946) or Blanche Lazzell (1878–1956).

For me, my passion is for what happens for an artist when that artist goes public, starts showing in the gallery, and starts selling their work. Artists grow, expand, and try all kinds of wonderful things. Sometimes things happen and at other times they don’t, but an artist needs faith to be shown in them just to get out of their own way. So, they need a gallery. I’m not hustling my gallery, but I’ve witnessed it. The walls have given the artists the chance to expand. There are now not a lot of galleries, and we are losing more each year. Artists need those walls to show their work.

CG Do you represent estates?

BW Yes, I do on occasion.

(Varujan Boghosian, Gilbert Franklin, Sue Fuller, Elspeth Halvorsen, Budd Hopkins, John Kearney, Anne MacAdam, Marjorie Strider, Selina Trieff, Ione Gaul Walker, Peter Watts, Nancy Whorf.)

If there was a Weinrich estate, I would say I represent it, but there really isn’t one. I’ve had many Weinrichs over the past 35 years, but they’ve come and gone.

(We discussed Weinrich and her brother-in-law Karl Knaths.)

I did a show called Creative Couples. It was an interesting series that involved over 100 couples, presented in both my Wellfleet and Provincetown Galleries. Sometimes it took forever to find the name of the wife of an artist from 75 years ago. Now consciousness has changed greatly so both parts of a couple are known, be they woman/man, woman/woman, man/man. The Creative Couples show included all art forms —poet, playwright, artist, dancer, sculptor, performance artist, curator. Yes, curator. I consider I’m a great collage artist as I use individual works of art by others to create a huge impact of amazing art and spirit for our viewers and for the artists themselves. (Laughter)

In many instances women made art but stopped working. They got married and raised children. So, it was really challenging to find them. And they were very, very talented! Then there were gay couples. We did a whole summer on that theme in two galleries. It was so much fun.

Knaths, whom I knew, was a great artist, but he does not now command the kind of prices of the New York School artists. None of the Provincetown artists do (there are a few exceptions), and I don’t talk money very well. Today, money around art is strange and I don’t understand what goes on any more. When a banana taped to the wall sells for $3 million, all is pretty skewed. I’ve shown a lot and sold a lot over the years. But I can’t give you financials because they change a lot and art is very personal.

Covid is a good example because it isolated us. People were not going out. I did window shows. I changed the shows and had window openings. If you buy a work and take it home you look at it very differently. Emotionally and energetically the work becomes so different. When people fall in love with a work of art it’s such a turn-on because they have just made a soul connection. It’s a personal connection to that secret part of us that’s called the spirit.

CG Over its 35 years has the gallery been self-sustaining?

(Currently she represents Donald Beal, Tom Boland, Paul Bowen, Polly Burnell, Mike Carroll, Lucy Clark, Ted Chapin, Carmen Cicero, Joe Diggs, Rob DuToit, Robert Henry, Grace Hopkins, Brenda Horowitz, Penelope Jencks, David Kaplan, Judyth Katz, Danielle Mailer, Deb Mell, Rosalind Pace, Erna Partoll, Sky Power, Blair Resika, Paul Resika, Laura Shabott, Bert Yarborough, Murray Zimiles.)

BW Yes! For me, it’s my life. The artists are my family. A lot of people refer to me as Berta Bee from my middle name which is the initial B. I’m seen as a pollinator. I spread spirit and talent for the world to see; in fact, thrive on! And luckily, we sell enough that I’m still in business and can afford to pay staff. In the past 35 years, I have had two galleries, one way down in the West End for ten years, and one in Wellfleet for ten years. It closed just before Covid.

CG You’re the longest running gallery.

BW At this point, Julie Heller (opened 1980) might be. I think she was here before me. I don’t quite know, but the gallery is not quite as active.

CG What about Cherry Stone?

BW They were here before me. (50-plus years) When the gals (Sally Nerber and Lizzie Upham) were active in Wellfleet they showed a lot of great artists. In fact, Lizzie and I were on the FAWC Board together until Lizzie died.

CG How many Weinrichs do you have?

BW About ten. I acquire them from individuals.

CG Do you acquire them at auctions?

BW Not that much. At auctions they are what they are. You don’t get to choose or determine quality. I don’t buy at auction that much. I don’t have that much cash flow to be buying art so much as supporting it. That’s the reality. We sell to walk-in traffic. We do a lot of advertising and some computer selling. We do a lot of mailing, like the show that is up now. We do a lot of different things, and the shows are knock-outs. I started putting up shows in New York years ago, so after 45 years, I know how to put up a show like this huge, complex group exhibition (Celebrating Blue). Grace (Hopkins) and I work on designing a show and it’s quite a creative process. It’s also true that after a day communicating with the spirit of each work of art when I go home, I don’t walk, I crawl. There is so much amazing energetic communication between me and each work of art, that I’m thoroughly enlightened and thoroughly exhausted by day’s end. A show is not complete until the art itself says it is! I learned that from an Andre Masson show (1896–1987, surrealist) I did when I was director of the Marisa del Re Gallery in New York.

Earlier, while I was assistant administrator at the Whitney, and full-time volunteer events fundraiser for FAWC, I met Marisa, who thought she would like to do a benefit for FAWC. I went to see her gallery and thought the gallery too small for a benefit. She was on the seventh floor of the Fuller Building in really a one-room gallery. Four months later, I got a call from her and she said, “I have a new gallery on the fourth floor of the Fuller building.” It was a huge space, which I helped her to renovate, and we opened with the benefit for the Fine Arts Work Center. I ended up hanging the show for her. I did the press release, and told her she couldn’t print the catalog as it was written, as she was now a major gallery in the Fuller Building. She asked if I could fix it. I’m not a good writer, but we fixed it and she said,” Why don’t you come and work for me?” So, again, “I got my job through Fine Arts Work Center,” so to speak. It’s part of the synergy of the art world, the way things flow.

CG Did you have any interaction with Walter Chrysler (1875–1940) when he was here?

BW I met him when he was here.

CG Did your father have any interaction with him?

BW He was on the board of the Chrysler Museum, until he noticed that a number of the pictures were questionable. Chrysler had a lot of fakes, and Dad was uncomfortable about it, so he resigned. I do remember Chrysler bringing in Warhol. I was pretty young then.

CG How about Joseph Hirshhorn (1899–1981)?

BW My boss at the Whitney subsequently went to work for his museum as the administrator, but I didn’t know him.

CG What about your grandparents in Provincetown?

BW My grandparents came in 1915. My grandmother hung around with Mary Heaton Vorse, as I said. She was a very important anchor of Provincetown. My parents came here, then Dad was in OSS during WWII. We subsequently learned it was the Monuments Men. He was in Rome for two years. He never talked about it. The people who did the research were all friends of Dad who went with him to college. They were all names I knew from my father. Dad couldn’t be drafted as he had rheumatic fever and was deaf in one ear. So, I knew he wasn’t a soldier. He never talked about it. Mother bought our little house in Provincetown while he was away.