New York City Opera Presents Monodramas

Three Sopranos Pushed to Thrilling Extremes

By: Susan Hall - Mar 28, 2011

MONODRAMAS

New York City Opera

John Zorn, Arnold Schoenberg, Morton Feldman

March 25, 2011

Through April 8

Conductor: George Manahan

Production Director and Set Designer Michael Counts

Choreographer Ken Roht

Costumes Jessica Jahn

Lighting Robert Wierzel

La Machine de l’Etre

Music by John Zorn

Ana Komsi, soprano

Erwartung

Music by Arnold Schoenberg

Libretto by Marie Pappenheim

Kara Shay Thomson, soprano

Neither

Music by Morton Feldman

Text by Samuel Beckett

Cyndia Sieden, Soprano

Photos by Carol Rosegg courtesy New York City Opera

George Steel, the general manager and artistic director of the City Opera, put together an exciting program of John Zorn, Arnold Schoenberg and Morton Feldman monodramas. Whether you love opera or hate it, you will be enthralled by these unsettling and beautiful musical dramas.

A male and female in evening dress are on stage as hosts for the evening. They greet us before the curtain rises, and wander through the sets of all three operas – suggesting that we the audience can also come on stage. Contemporary dramas like these often break down the Chinese wall between on-stage actors and the audience to moving effect. Antonin Artaud, a man of the French theater who inspired Zorn’s monodrama, felt the audience should be exposed rather than protected.

Sounds are more important than words for a singer and ordinary orchestral color often disappears to focus attention on the sounds of glockenspiel, tam tam, marimba and harp, on thickly built harmonics, which all arrest the ear. For Monodramas, conductor George Manahan brings challenging scores to life.

Serendipitous meetings and absences are on stage in all three operas. Steel brought Zorn and production director Michael Counts together. They found themselves on the same emotional and musical page.

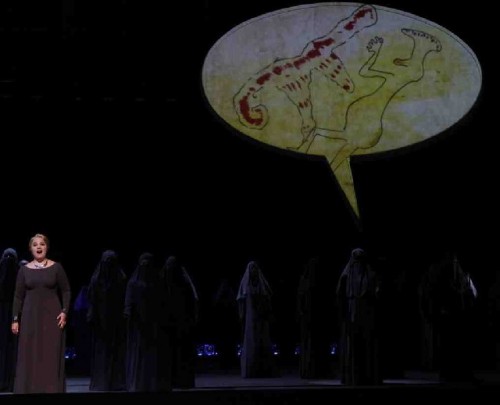

In the hands of the gifted production team headed by Counts, an ensemble of dancing actors mime gestures, choreographed by Ken Roht. Dressed at first in long grey robes with half masked faces, the ensemble actors are often stripped to reveal long luminous dresses and sometimes a red suit. Mirrored boxes hang from the sky and twirl as they catch and cast off shafts of light, a forest is blanketed with fluttering red leaves and rectangular speech balloons are filled with Amy Whitney’s fascinating animations of Artaud drawings.

All three composers were influenced by the visual artists around them. Schoenberg himself was a good painter, and a friend of Kandinsky. Feldman was at the center of the abstract expressionist movement in New York. Samuel Beckett, who wrote the text for Neither, once spent six months in Germany just looking at paintings.

John Zorn was inspired to compose La Machine de L’Etre by the drawings of Artaud. Zorn had grown up in Queens near Joseph Cornell, who created tiny universes comprised of found objects which resounded in small boxes. These boxes, like Zorn’s music, suggest a logic which doesn’t exist. This matches Zorn’s notion that every piece he has written “is like a little frame,” a musical story symbolized by sounds not words.

Ana Komsi, a Finnish soprano in her City Opera debut, emits wordless sounds with a pure soprano and indicates also the variety of human sound. Zorn likes a pure voice without vibrato, but encourages the use of the shading and sculpting that Komsi used. For audiences open to new experiences, La Machine de l'Etre packs the wallop of William Kentridge’s art in The Nose.

Early Schoenberg fascinates Zorn, “…where he wasn’t quite sure what he was doing, He needed something to ground his work, so he used text or a dramatic subject.”

Erwartung is Schoenberg’s evocation of an analytic session on Freud’s couch. As old fashioned as this may seem today, the nightmare world of dream, which flickers between real feelings of love, of fear, and yearning teases always: is it or is it not real? The wandering soprano, Kara Shay Thomson in her City Opera debut, sang beautifully ranging from anxiety to full erotic feeling. Another soprano who sang this piece recently in New York retired for years to a nunnery to prepare. Whatever Thomson’s methods, her luscious performance captures Schoenberg’s musical comment on women whose character resembles Natalie Portman’s in Black Swan.

When the composer Morton Feldman met the virtuoso of the word, Samuel Beckett, for the first time, they instantly found common ground: they both hated opera. Actually Beckett loved Gilbert and Sullivan, which he often performed on his piano, substituting his own ribald libretti for Gilbert’s.

Feldman had just received a commission from Opera Roma and asked Beckett to write a libretto. Although Beckett was a man who undertook collaboration with extreme caution, he instantly said yes. Weary of the word, he liked Feldman’s approach. Neither arose from this accidental encounter. Although they did not work together, Feldman remarked, “I wanted to remain loyal to his (Beckett’s) feelings as well as my own. There was no compromise because we were completely in agreement.”

Feldman began composing before the text arrived, but when it did, he wrote Beckett: “I have found a way to use your text quite naturally.” He discusses the breathing and staggered rhythms that give such pleasure in performance.

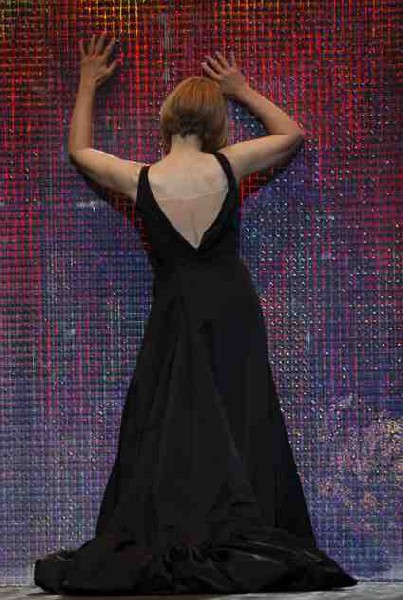

Cyndia Sieden would have pleased these two giants. Beckett’s 87-word text is mixed with pure soprano sound centered mainly between a high F sharp and a very high C. Sieden sneaks up on her lines and then dissolves them. The repetitions are not iterations, but returns, which evoke rather than numb. Even the sung words are often blended into sound, clearly the composer’s and Beckett’s intent. Neither like its creators is not interested in meaning, but rather in gesture. Sieden, in her glorious soprano, captured the difficult song line perfectly, keeping her voice comfortably at a high pitch.

The City Opera orchestra breathes life into Neither from the high piccolo to the tam tam, marimba, double bass and harp. In fact all sounds from cacophony to lyricism were masterfully performed.

While the setting and the ensemble choreography varies from piece to piece, all are tableau vivants – living pictures, alive and art, moving and at rest, stirring and still, a mixture of the farcical and the sublime. They echo the most serious of matters, like a stabbing and a hanging and also the Keystone Kops.

Samuel Beckett loved music and went to live concerts nightly. Good footsteps to follow. Come to Monodramas early and often. A splendid evening full of energy and spontaneity where uptown and downtown mix.