St. John Passion at Carnegie with Bernard Labadie

Ian Bostridge a wonderful Evangelist with Les Violins du Roy

By: Susan Hall - Mar 26, 2012

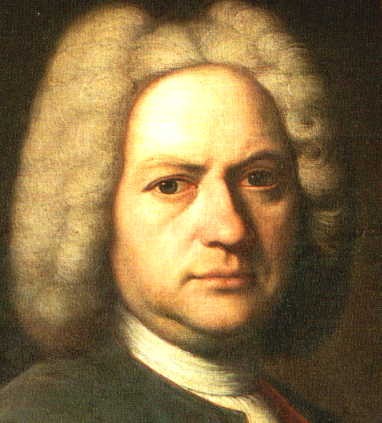

St. John Passion

By J. S. Bach

Conducted by Bernard Labadie

Les Violins du Roy

La Chapelle de Quebec

Carnegie Hall

New York, New York

Singing artists: Ian Bostridge, Neal Davies, Karina Gauvin, Damien Giullon, Nicholas Phan, Hanno Miller-Brachmann.

March 25, 2012

The St. John was Bach’s first Passion, but often takes second place to the St. Matthew, which is more richly developed. Under the baton of Bernard Labadie leading his Violons du Roy, the St. John gives exceptionally moving pleasure. With an often brilliant group of singers. Carnegie Hall was a perfect setting.

Labadie is an early music specialist, who makes every performance seem current. Bach provides help. This performance was divided into two parts as Bach intended. The first before the preaching or in our case the intermission, and the second, after. We are immediately put on notice as the chorus opens with “How glorious is your name in all lands.” Two ways of glorifying, making known and making Godlike, are sung. A kingdom is to be established not by sword and armor but by word and faith, an admonition not much followed today.

Above a moving bass in short notes on the organ, strings prepare a figure of praise and thanks, and a sad melody floats above. Long sustained tones of flute and oboe begin their mournful song. The chorus rises above in praise as the funeral hymn of flute and oboe sounds on. Glory and suffering are then offered up and continue to work together, with and against each other throughout the Passion. The flutes and oboes sigh and wail and stress the thoughts of the passions. The strings glorify.

The St. John is unique among its contemporary passions focusing not so much on what the passion means as on the nature of Jesus. As the music continues, we are swept up in the story as passion play. This is only one segment of the gospel, but surely it is its heart including the betrayal and the acceptance, even welcoming of his fate, by Jesus of Nazareth.

When his assailants arrive, Jesus does not wait, but goes out to meet them. "Whom do you seek," he asks. "Jesus," they say. "Ich bin," he replies, which means more than I am, but rather I am the one, the son of God. Bach moves from the fifth to first or home pitch a cadence both forceful and firm. Capturing every dramatic opportunity in the music, Bach and the performers draw us in.

While records of Bach’s composition do not tell us much, it is clear that he has borrowed from moving sources beyond John’s gospel. In Peter’s denial, Bach lifts from Matthew: “Peter went out and wept bitterly”, and he also lifts the rending of the veil at the temple and the earthquake that accompanies Jesus’ death. Bach musically pictures the great scenes of trials before the high priest and Pilate. An air of excitement is captured.

The chorus creates the fanaticism of the crowd. “This was no evildoer” and “we should put no man to death," are sung in an extended chromatic theme to appropriately dreadful effect. At intervals, "crucify him" is repeated in furious ascenind semiquavers, as if the maddened crowd were raising a thousand arms toward heaven. Even in the themes like “We have a law: and “If thou lettest the man go” there is something wild, even as the music slows. Over and over Bach uses drama in the music to tell the highly dramatic story.

As the recitatives begin, they are simple, accompanied only by the organ and bass. The great tenor, Ian Bostridge, declaims in strict observance of the word, from time to time slipping over into arioso as Bach paints with music, as in the words about Peter: "And he wept bitterly." When Bostridge reports, “Then Jesus took pilate and scourged him,” there is a long figure over a sharply marked bass suggesting blows. In the arioso and aria that follow, Bostridge moved through harmonies fluctuating between major and minor. The violas are veiled, like a smile through tears. In the arching curves of the melodic lines, the rainbow of the text seems to appear. Bostridge takes phrases that are often too drawn out, at the lovely pace.

In arias, the story stops, as the singers reflect on unfolding events. In an aria, “Ah my mind” at the end of the first part, Bostridge sang wild and passionate grief. He seems to be a man rushing back and forth in despair. The end does not return, but rather shrieks. The arias are special events and fresh.

When Neal Davies as Jesus finally sings his last words, “It is finished,” the words come from a falling sequenec as Jesus’ head sinks in death.

Chorales are like a Greek chorus speaking for the congregation. At times the chorales appear in ceaseless first person, an imaginatively dramatic gesture. Yet there is no sentimentality, only simple, elevated pathos.

Bach may have thought that long drawn out recitatives would make the congregation weary. The occasional choruses and arias with splendid instrumental effects in addition to the exciting declamations of Ian Bostridge make the church music into a concert.

When it was first performed, the listening congregation was encourgaed to join in song at the chorales. In a small chapel just outside Boston, Bach’s chorales are provided in addition to the Bible in the pew shelves, perhaps for the same purpose.

No rest for the weary this afternoon at Carnegie. You wanted to hear every note in Labadie’s exciting St. John Passion.