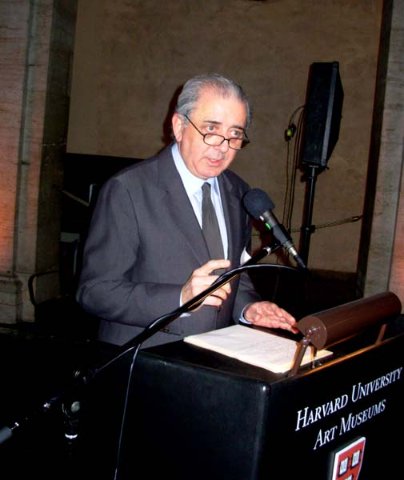

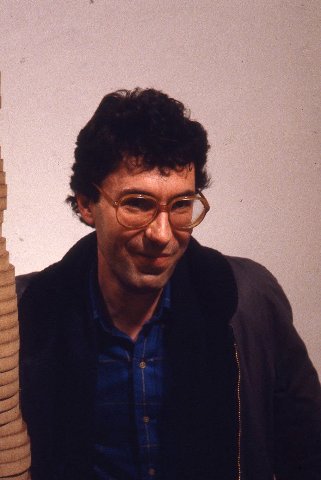

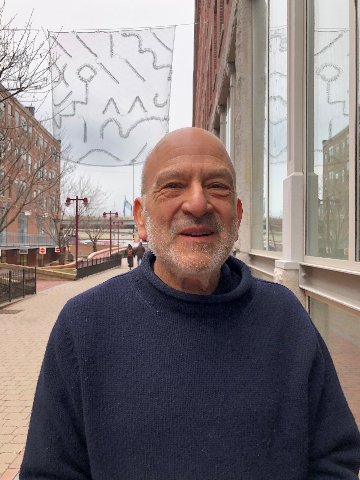

Boston Gallerist Arthur Dion

Gallery NAGA on Newbury Street Since 1977

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 25, 2020

Today, Gallery NAGA prevails as a reminder of when Newbury Street was regarded at Boston’s gallery row. Constant rent increases and other factors led to relocations and closures. NAGA, founded as a cooperative in 1977, has a stable lease with Church of the Covenant.

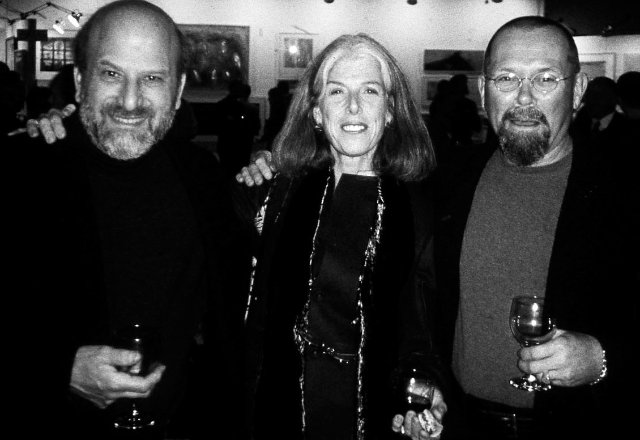

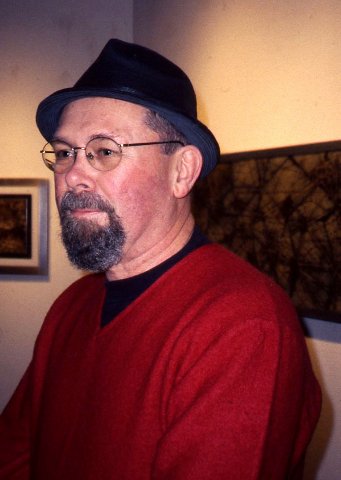

In 1982, Arthur Dion was hired as director. He soon became sole owner and is now its emeritus director.

Including his taste for painting, Dion describes himself as a native Bostonian. He was born in Jamaica Plain in 1946, but lived in East Boston from 1949 to 1952. After Chicopee High School he graduated from Harvard, class of 1968.

From the Red Sox to Yankees, Met to MFA, ICA to MoMA, Boston has had a contentious relationship to New York. In the arts, this has entailed embracing traditional and arguably more conservative values. For NAGA it has meant not trying to surf the next wave.

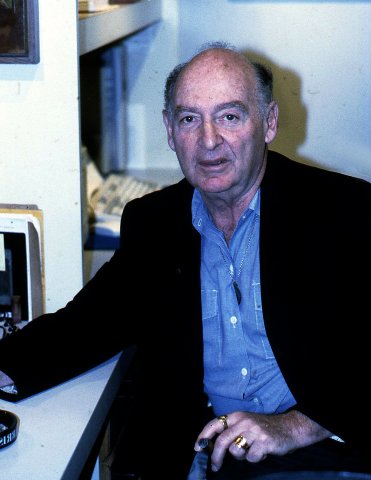

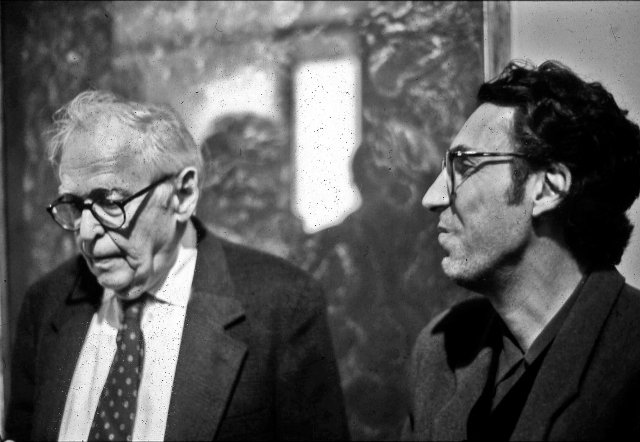

The high standards and excellence of NAGA artists, however, has never been in doubt. Henry Schwartz (1927-2009), for example, provided an aesthetic and historical connection to the seminal generation of Boston Expressionism during the post war era. Some years ago, Dion commented “I challenge you to name a more important Boston artist since Hyman Bloom, the post war departure of Jack Levine, and the death of Jack Kramer. Henry was central to the development of the new art scene in the mid-1980s. In a 35-year span of time nobody was more important than Henry Schwartz.”

The gallery has earned a nation reputation pioneering the field of studio furniture. In the secondary market work by Judy McKie sells for six figures.

Significantly, NAGA has allowed exceptions. The gallery represented holographer Harriet Casdin-Silver who died at 83 in 2008. Previously Dion said “I’m in love with Harriet. She is one of the most challenging artists we represent and may be the most important artist I will ever work with.”

Early on an established gallerist told him, “You seem like a nice kid, but take some advice. You will never make it selling local artists.”

Then and now Dion has pursued his own path. It is one that others have respected and followed.

Charles Giuliano Was it Cynthia Howard who started the gallery?

Arthur Dion She was a member of the congregation of The Church of the Covenant. She was present at the creation of Gallery NAGA in 1977, along with a healthy group of Boston artists.

CG It was a cooperative until what year when you came?

AD 1982.

CG Didn’t you come from an arts organization in Providence?

AD I was founding director of an alternative high school there, School One. It is now celebrating its 47th year of operation. It’s a welcoming, student-centered, very creative educational institution. I and a group of other people were present at that creation. I served as its director through 1978.

CG How long after Harvard was that?

AD To the founding of School One, five years. In that period, I did a number of things. I spent two years on design, carpentry and construction, which was the school’s initial interest in me, because they had an empty bowling alley with the lanes filled in. They needed someone to design and build the classrooms as an educational project with the students. Not only did I have those skills, but I had also taught for a couple of years in Boston and Concord and had an advanced teaching degree, so it was a fit.

CG What gets you from there to Newbury Street?

AD Serendipity, and, as a Buddhist teacher told me, if you’re a good person, then good things happen to you.

At School One, Alfred Quiroz, a smart, talented, interesting painter from Tucson via the San Francisco Art Institute and RISD (Rhode Island School of Design), ran our art department. When we got the second floor of the building, the English teacher said, “We need a library,” and the science teacher said, “We need a lab.” Alfred said “Why don’t we start a gallery?” I thought that was a wonderful idea.

We opened the School One Gallery and showed ourselves and our friends. We thought that everyone teaching at Brown University and RISD was hopelessly retardataire and academic, with nothing interesting to say. We started to get covered in the papers and to sell things, and we were having lots of fun. We were having openings, the whole bit. I thought, gee, I wonder if you can make a living doing this?

I had gone to the school as a project. Because of my history, I had a lot of ideas about education that I thought might be implemented. But I didn’t aspire to a career as a headmaster or a director of a secondary school.

As with everything I’ve done, I thought, I want to leave this successfully and for it to continue when I’m done. I don’t want it to miss me or be at a loss.

To answer more directly, I turned down a job offer as third banana at New York’s OK Harris Gallery, under Ivan Karp and Carlo Lamagna, because I thought I couldn’t move to NY City and make $12,000. That was in 1981. I thought, “I’ll have just enough money to go home.” If I were to do it as an adventure, or with a lover, maybe. And it wasn’t giving me the creative opportunity I was interested in.

CG How did you get in touch with NAGA? Was Cynthia planning to leave? Was there a job notice? What was the process?

AD The place was tanking. Over a five-year period they did well, then better, then less well, then terrible. There was no following for the gallery. The individual artists had followings that would support them. They rotated showing and working the place. The artists had support for their first and second shows but there wasn’t support for the gallery as a whole.

They threw a ridiculous amount of money on the table, $13,000. It was a bid to hire professional management.

CG So you didn’t buy the gallery. You came in and were offered a salary. Then you took over ownership, and it ceased to be a cooperative gallery.

AD There was a segue.

CG That meant that artists no longer paid dues. But you then called the shots.

AD What happened is that the place started to do well with my leadership. The majority of the artists thought, well, screw all these meetings. I want to go back to my studio, job, family. I don’t need to run this place anymore.

I embraced not only the artists but the ethos that had brought them together. I didn’t ask anyone to leave. Some didn’t want to be in a gallery that wasn’t in its original structure.

CG Who were the artists in the initial group?

AD Henry Schwartz (1927-2009), towering above all others in every sense. Peter Scott, a print maker and draughtsman who taught at the Museum School. Bob Siegelman, Brenda Star, David Thomas, Tim Hamill, Theresa Monaco, Hap Paull, David Barbero, Bill Georgenes, Susan Rogers. Paul Shapiro was a member but was leaving for the Southwest.

Roster of current NAGA artists: Sophia Ainslie, Joseph Barbieri, Ken Beck, Gerry Bergstein, Peter Brooke, Lana Z Caplan, Harriet Casdin-Silver, Nicole Chesney, Nelson Da Costa, Alice Denison, Yizhak Elyashiv, Benjamin Evans, Robert Ferrandini, Rick Fox, Dinorá Justice, Jaclyn Kain, Masako Kamiya, JooLee Kang, Martin Kline, Mary Kocol, Keira Kotler, Bryan McFarlane, Todd McKie, Joseph McNamara, George Nick, Stuart Ober, David Prifti, Richard Raiselis, Harold Reddicliffe, Louis Risoli, Terry Rose, Henry Schwartz, Peri Schwartz, Peter Scott, Robert Siegelman, Esther Solondz, Brenda Star, Ed Stitt, Cheryl Ann Thomas, Irene Valincius, Peter Vanderwarker, Julia von Metzsch Ramos. Furniture Makers: Garry Knox Bennett, Andy Buck, John Eric Byers, John Cederquist, Hank Gilpin, Jenna Goldberg, Thomas Hucker, Yuri Kobayashi, Judy Kensley McKie, Bart Niswonger, Tommy Simpson)

CG You worked with a number of those artists for many years.

AD Yes, Peter, Bob and Brenda are still with the gallery.

CG When does Paul Rahilly come in?

AD The early 1990s. I have a Charles Giuliano story about Paul Rahilly. When you were at your charmingly hostile best, you would basically pick fights as a form of aesthetic engagement. You came in and utterly trashed Rahilly’s work as hopelessly backward looking and mannered.

CG True.

AD But that’s like saying, “This egg is rotten. I see a brown spot on it.” You were looking at the shell and not considering its interior. Rahilly’s work is profoundly interesting because of its inversion of realist painting formulas. He was not painting a woman of standing surrounded by objects that speak to her interests and qualities. He was painting anonymous women, made up of a combination of parts of different women who had modeled for him, surrounded by objects with absurdist relationships to her form, that are there for the purpose of formally amusing juxtapositions. He made paintings he described as enjoyable to rub your eyes on.

CG For example ducks, barnyard creatures, and cows. As a whacko extension of Barbizon paintings with nudes. Done with a Sargentesque flair entailing a fluid and facile brush.

AD You came in and propounded, “When the Winter Palace is stormed, the walls will be hung with Rahillys.”

CG What a lovely analogy.

AD Not bad. Worth remembering. Paul came in the early 1990s around the time that George Nick joined the gallery.

In the late 1980s I had been doing a lot of looking and thinking about the character of the gallery. We developed studio furniture in the mid-1980s. It’s an important part of the gallery for which we are known nationally. The circuit has shrunk. We are now one of very few galleries showing museum-level studio furniture.

CG Who was your partner in that pursuit?

AD Initially, as a business partner, nobody. In identifying the field, Deborah Daw, who was at BU for a time and was engaged with the studio furniture being done there in the Program in Artisanry. She did the first show of studio furniture with me. She was a volunteer to an advisory group helping the gallery. That’s when we first showed Judy McKie, Tommy Simpson, Tom Loeser, Mitch Ryerson, Rosanne Somerson (now the president of RISD), Alphonse Mattia, and Ed Zucca.

It was a smash. Three years later (1989) Ned Cooke did New American Furniture at the MFA (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which toured nationally. There were about 25 people in that show, some 15 of which we were showing at NAGA.

At Clark Gallery in Lincoln, Meredyth Moses started showing studio furniture at about the same time that we did. We were competing. Some makers were loyal to her, and some to us. Some were loyal to both of us, like Judy McKie.

When New American Furniture was scheduled everyone wanted to have a show up at the same time. I tried to figure out how to get the drop on Meredyth. Her weak point was being in Lincoln. I invited her to do a show with me. On a handshake we agreed to split expenses and profits. We had an amazing show. We each bought major pieces which we both still have. When it was over, we agreed that it was wonderful and for the next twelve years we split every dollar of studio furniture expense and revenue at the two galleries. On trust, with no paperwork. She was my sister, although we were still trying to outdo each other.

CG Yesterday I had lunch with a friend who is a master restorer of stone sculpture and masonry. His firm does a lot of cemetery work. The question came up as to whether he is an artist. That led to a debate about art object vs. artifact. As well as the issue of originality. Is craft art? Is the Victoria and Albert a museum of fine arts or a collection of master craftsmanship? During the industrial revolution its intent (initially as South Kensington Museum) was to collect examples of craft work in all media as an inspiration for British industry.

The industrial revolution ended cottage industry, a reaction to which, launched the arts and craft movement which the V&A embraced. For me, a superb tea pot is a craft object and not a work of fine art. What begs the question is an object like Cellini’s salt cellar. It has the element of sculpture, Neptune and Venus, but sat on the table of Francis I as a functional part of dinner service. As seen in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, from which it was stolen, it is regarded as an art object. I actually brought up the example of Judy McKie who makes furniture as well as purely fine art prints and sculptures. Is she an artisan, master furniture maker, or artist?

AD When I was a teenager, I saw Oscar Levant on Jack Paar. Levant was known as much for his instability as for his considerable talent as a pianist and actor. Jack asked probingly, “Who are you?” Levant answered, “There is a thin line between madness and genius. I have erased that line.” I think “art or craft” is a false dichotomy. It was set up as part of the Beaux Arts movement in France, before which furniture included paintings. Anything that furnished a house was considered furniture.

At NAGA we addressed this by presenting studio furniture to what was an audience for painting in a painting gallery without explanation or justification, as if it made sense and had every right to be there. The making and presenting transcends the question of function. Although, I have to acknowledge, in the case of studio furniture presented at NAGA, we always insisted on superb function. We didn’t show objects that used the locus of furniture for sculptural work. It’s not exactly a fudge, but more a matter of having two simultaneous positions. They might at first appear to be in conflict, but we didn’t experience it that way.

I was at a reception at the community arts center in Hopkinton where I volunteer. I was talking to another volunteer and asked if she were an artist. She said, “Oh no, I just cut things up and paste them together.” I said, “Why isn’t that art?” She said, “Oh no. I don’t have the sensibility of an artist. Not like this work,” gesturing toward mixed media sculpture. I said, “I don’t see a difference between what you are doing and the work of this artist.” She didn’t see the connection. “You’re doing collage, are you familiar with the work of Kurt Schwitters?” I got on my high horse and told her how hard it is to do collage. Most artists who do collage, it looks like collage. It doesn’t look like an individual sensibility’s work particularly. I said you may view what you choose to use as everyday, flowers and such, but those are just your formal choices. I think you’re an artist who does collage.

Judy (McKie) is an exception in that she does furniture and 2-D work that falls into the category of prints and drawings. Cliff Ackley (Museum of Fine Arts curator) just did a show of prints in Concord and included Judy.

I understand that the distinction (art vs. artifact) has been important in society for a long time. For a couple of centuries, the distinction has been very sharp. Personally, it’s not very meaningful to me, or useful.

CG NAGA was also early to explore artists’ glass.

AD David Bernstein with the Glass Veranda was more responsible for that than I was. We did a show called Mass Glass. He knew the field while I did not. I was intrigued, had the space and the latitude, and said, let’s do a show together.

Going back to Paul Rahilly. In the late 1980s nobody was particularly interested in painting. Anything but paintings was what most people were interested in. Especially people running galleries. I felt that the best way to run a gallery was to show things that seemed important to me. Painting held a real sway over me. I realized that exploring that sensibility should be the identity of the gallery. Just when everyone was saying, “Painting is dead,” I was saying, “Painting!” That created a magnetism that brought not just Paul and George Nick, but Todd McKie and Gerry Bergstein, Bob Ferrandini, Peter Brooke, and many others.

CG Isn’t painting also uniquely a Boston sensibility?

AD I’m a Boston boy, and a product of that. I’m interested in painting, and it is hard to extract the Boston factor.

CG Did other Boston galleries share that interest?

AD Not so much then, though Alan Fink (Alpha Gallery) was always interested in painting. Barbara Krakow and Nina Nielsen to a good extent. Most people liked painting, but thought painting was not what was happening. A long time passed before most people thought it was okay to be interested in painting again.

CG Formerly, Newbury Street was Boston’s gallery row. Now Gallery NAGA, which you are no longer with day-to-day, is a singular survivor. There are a number of art boutiques touting expensive multiples by famous artists, but they do not promote individual artists as we understand the function of galleries.

AD There are any number of boutiques selling a variety of things. I am still connected to NAGA, Charles.

CG In what capacity?

AD I am engaged with gallery activity. I am a fractional employee. I visit with regularity and carry out various projects here and there. Meg White, who joined the staff in 1999, now operates the gallery wonderfully, aided by Andrea Dabrila. In fact, once I got out of the way, the place took off.

CG I was under the impression you were taking a very long lunch.

AD I am. That’s accurate. It’s interrupted, occasionally, by a bit of effort on behalf of the gallery.

CG What are your hobbies? Do you play golf?

AD That’s a funny question. I moved into a condo in Milford that’s built in the midst of a nine-hole golf course. It’s like I should play golf.

CG How do you pass the day?

AD I’m engaged with meditation practice and Buddhist study. I’m involved with a number of groups and relationships. That’s my primary orientation.

CG Let’s get back to the demise and fall of Newbury Street as a matrix for the Boston art world.

AD What you say is largely true. Bob Klein (photography) is still there, as is Barbara Krakow. Fundamentally, the scene shifted to the South End (SOWA). For those of us still on Newbury, it seems like the right place to be. It isn’t what it was and has transformed in character in many ways apart from the gallery scene.

(There have been numerous attempts to establish galleries other than on Newbury Street. An important early experiment, was Parker 470 across from the MFA, which entailed partners Portia Harcus, Barbara Krakow, Joan Sonnabend and Phyllis Rosen. When that closed Harcus and Krakow moved to Newbury Street, steps from the Ritz, before separating. Sonnabend became a private dealer working from home on Beacon Hill. On Congress Street in the early 1980s there were loft-scale spaces for Lopukine/Nayduck, Helen Shlein, Cutler/Stavaridis. For a time in the late 80s, the leather district near Chinatown had Mario Diacono, Portia Harcus, Howard Yezerski, Thomas Segal. In the 1990s Sullivan/Genovese was the first to locate in the SOWA district. Papermaker Rugg Road, with Joe Zina, became the seminal Bernard Toale Gallery in the district after a short stint on Newbury.)

CG There are only two ways for galleries to remain on Newbury Street. One, to own your building, which was the case for Nina Nielsen. Or to have a long-term affordable lease as NAGA does with the church. One needs to be making a lot of money with deep pockets. The challenge is to keep up with constantly escalating rent.

AD There’s a funny circumstance behind almost every art gallery. Most galleries stand apart from the norms of retail operations.

CG You have long been a sharp observer of the ebb and flow of the Boston art world including the ICA and MFA. You were unique in sleeping with the enemy represented by a relationship with former MFA director, Malcolm Rogers. He was not seen as a friend of Boston artists or contemporary art in general. There was not a lot of progress on his watch, with curator Cheryl Brutvan doing his bidding. Shows focused on cars, guitars, Wallace and Gromit, and celebrity photographers Yousuf Karsh and Herb Ritts failed to impress. He showed fellow Brit, David Hockney, which resulted in a nice gift/acquisition. But you appeared to have a cozy relationship with him. The curatorial field of Rogers was British portrait painting. His taste, if that is the word, ran to kitsch such as Dale Chihuly which again begs the question of art vs. craft. A Christmas tree-like tchotchke in the atrium of the Art of the Americas is an enduring reminder of Malcolm’s splashy, populist exhibition of his vulgarian kitsch. It is little wonder that the museum made scant progress for modern and contemporary art on his watch.

AD I defer to you in terms of knowing the ins and outs of the scene. Almost everyone is a flawed and struggling human being. Despite differences of opinion it’s not that hard to connect with other people, if you can relax your grip on a view of the world the way you think it should be, but isn’t. I liked Malcolm but disagreed with him about lots of stuff. From a certain point of view, he was congenial and open as a person. I argued with him and criticized to his face decisions he made which I didn’t think were healthy for the museum or the town. I enjoyed my contact with him and thought it was important, as the director of a significant gallery, and in my role with Boston Art Dealers Association, to be able to talk to the guy. To pick up the phone and talk to him and have him return my calls. Write a note and get one back. To be able to talk about things. There aren’t that many villains in the Boston art scene. The lines of conflict have a gossamer quality.

CG What was your relationship with the ICA?

AD There is a lot to say. I championed its move to the waterfront. NAGA was a significant contributor to that campaign. You have written about the history of the ICA in greater depth than anyone I am aware of. You know the players pretty well.

I enjoyed Milena Kalinovska a great deal. For decades it’s been a tradition that NAGA sends gifts to its artists once a year. We send them things that are inscribed with the word NAGA. It’s an ongoing challenge to come up with something that’s better than last year. We have had letter openers, corkscrews, magnifying glasses. When we gave out magnifying glasses Gerry Bergstein called Todd McKie and asked, “Do you think they gave the younger artists the same gift?”

One year we did baseball caps. Clients would come in and want one. We would piss them off saying, “This is only for artists.” They would get angry and say “After all the money I’ve spent with you, you can’t give me a lousy baseball cap?” We were very rigid about this.

Another year we did black boxer shorts. With white, all caps, NAGA on one leg. For some reason, I made an exception and sent Milena the boxers. She called me and said “Arthur, I know we’re friends, but now you’re sending me lingerie!”

I’ve always had an antithetical relationship with the ICA, more in some ways than with the MFA. I always felt that the MFA had an honest disinterest in most of the things I was doing. Where the ICA had a perverse definition.

David Ross had a great take, with Elizabeth Sussman and, for a time, with Matthew Teitelbaum (now director of the MFA), regarding artists working in Boston of particular interest. I didn’t always agree, but they were very vigorous in championing people who they thought were important locally. That has so drifted. The ICA was vital to Boston artists, and I’m not sure it is anymore.

CG There’s the Foster Prize and its annual exhibition of finalists.

(It is a reconstruction of the Boston Now series that started with former ICA directors Sue Thurman, Drew Hyde then, after a lapse, was revived by David Ross. Briefly, during the time of Amy Lighthill as curator, the MFA organized a survey of contemporary Boston artists. Through adjunct curator, Barry Gaither, who is director of the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, the museum has shown interest in collecting and exhibiting artists of color. It has a program of acquiring the work of women through the erratic Maud Morgan Prize. Recently, correcting glaring neglect, the MFA had a major exhibition of the Boston Expressionist, Hyman Bloom. With former ICA curator Matthew Teitelbaum as director there is hope for change at the MFA.)

AD There is the ICA’s Foster Prize, and I don’t want to say it’s token. It’s real. It’s valid. It’s important. But it seems like the exception that proves the rule. The curatorial program doesn’t seem to want to engage with issues that concern Boston artists. No matter what the issues are, the issues are not that different. On some level we’re always talking about the same sorts of things.

CG (When Jane Farver (1947-2015) was director of the List at MIT, the curator who worked with her, Bill Arning, made every effort to connect with Boston artists. He knew the pulse of the city and engaged in a dialogue. That did not result in programming changes at the List, but was significant in involving many artists with its outreach and vision. The Farver/Arning period at MIT was a learning curve for many of us. Jane was enormously patient and welcoming. I never fully grasped their advanced ideas, but did not feel estranged from that vision. By contrast, I have felt no direct contact with ICA programming since the era of Ross and Kalinovska. The engagement with them was often contentious, but lively and provocative. Then and now they took my calls and were willing to discuss issues. Ultimately, that changed and enlarged my understanding and embrace of contemporary art. Their programming was more effective than the sense of disconnection today when visiting the ICA.)

I feel that the ICA miscalculated with the space-squandering design and landlocked isolation of the relocation to the waterfront.

AD The real tests are does the ICA connect with the arts community? Do people from out of town want to visit? For me, it’s all about programming. We can agree or disagree about the architecture. The programming has got to work.

CG There’s just not enough space particularly now with a decision to collect, show and store work.

AD Museums always can use more space, but you’ve got to do well with what you’ve got. Your points about a permanent collection make a good argument. But I’m not the right person to ask about that because I have been so disengaged for the past five years, anyway. Actually, six this month that I have been at a remove.

CG For that I wouldn’t put all the blame on the ICA. We live within walking distance of MASS MoCA. From year to year there is little that engages me. Now and then there is a spectacular exhibition like the current one, When, by the South African artist Ledelle Moe. In general, contemporary art is less engaging for me than it was when I was most active as an art critic. During the counterculture era of the late 1960s and 1970s, my very being revolved around all aspects of the arts.

AD Might it be that our taste is passé?

CG Totally. We are wallowing in the dyspeptic legacy/dinosaur phase of life. When you engage with young curators, they are committed and have a lot to say about the work on their watch. As it was for us when we were their age. But I no longer have the commitment and education to keep up with their dialogue. When, as with the Ledelle Moe show, there is an engagement, I make every effort to grasp and write about the work. But it takes more to arouse my interest. That happens now and then.

You have had a career primarily of selling works by Boston artists to Boston collectors.

AD By and large.

CG What is the resale value of work that you represented? In general, dealers in the secondary market and appraisers say that they have to tell clients that their collections are not particularly liquid. Museums are selective, and it is difficult to donate more than a few works. With baby boomers downsizing, the market is flooded. The next generations are not interested in inheriting the art and antiques that their parents acquired. They are less interested in planting roots and maintaining large homes and estates.

AD The resale value varies dramatically. For some work it would be relatively hard to sell at the price you paid. For others you might sell for what you paid or for whatever the work of that artist is going for now. Some work has appreciated hysterically. Work by Judy McKie, at auction, is into six figures. A pair of benches went recently for close to $400,000.

CG That’s remarkable, but represents perhaps one percent of the artists you have shown.

AD I would say that there is a broad middle where the work is commercially viable.

CG I’m trying to get a broader sense of the relative value of Boston as an art community. Compared to larger and more viable urban markets like NY, Chicago, LA, Miami, Santa Fe, Philadelphia.

AD I have two responses. One recalls an earlier conversation when you asked to interview me. At the time I said, “Charles, it’s not that important or really of that much interest. We are going to fade from memory. That’s really okay.”

CG Do you mean you and I as individuals or everything that we fought for and represented?

AD The former and most, if not all, of the latter. The other answer is that I’m not sure that the proportion of art made by artists in Boston in the past 50 years that will be of interest to anyone in the future is any smaller than that of art made by individuals in Chicago. Most artistic activity is washed away by time. We’re a much smaller universe than New York. We don’t have the same cultural impact, which you know as well as I do. You could select a half dozen artists who have worked here, put them in New York, and they would have had much more important careers.

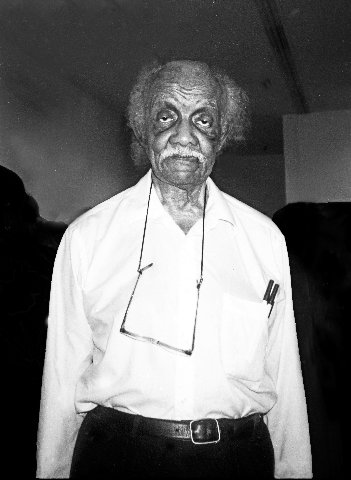

CG Let’s talk about an artist in particular, Allan Rohan Crite (March 20, 1910 – September 6, 2007). He was one of the first African-Americans to graduate from the Museum School. You opted to represent him when he was then quite elderly. You felt that he was an important historical figure.

AD He is.

CG I was present during a NAGA exhibition of his work on a day when MFA curator Cheryl Brutvan visited. She was in the gallery on other business and approached you at the counter. We have different characterizations of how she did or did not interact with the work on view.

AD She glanced at it.

CG I didn’t feel that it was my place to comment on her obvious snub of the work. I was just there to observe. That behavior seemed to represent everything that was wrong with the MFA, particularly Malcolm Rogers, who she worked for and who endorsed her attitude.

AD We can pick on Cheryl, but this is a racist art scene. And a pretty racist city. But I’m not picking on Boston. You can say that about any comparable city in the country. There are skilled, wonderful, interesting, charming Black artists in this town - and there always have been - who can’t break into the fundamentally white art scene.

Allan Crite is shown at the MFA now because a series of cultural and political circumstances have changed. But that doesn’t change the fact that, at that time, most of us couldn’t see past our blinders. I had practically no success presenting Allan’s work, aside from some wonderful purchases of my own. What you don’t know is that my engagement with Allan far predates my engagement with NAGA.

At the School One Gallery, we started to do more ambitious things. One day Leonard Smith, who was teaching painting, said, “You have to come with me tonight to the Rhode Island Black Historical Society to see a presentation by this painter, Allan Crite. You’re going to love it.”

Allan showed images of his work, and I was knocked out. He said, “If any of you would like to visit me in Boston, you may.” After the talk I told him I wanted to take him up on that. This was probably 1980. Allan was not that old at that point. Younger than we are now, but not that old. His house in the South End was a museum. He was completely charming, with refined and shy manners. He was sweetly and tartly funny. His work was ambitious and, in many ways, courageous.

I said, “I want to show your work.” At the school in Rhode Island we staged the largest exhibition of his work that had been mounted to date. There were 51 objects, including ecclesiastical pieces, altarpieces, illustrated spirituals, family portraits.

I invited Barry Gaither to give a talk at the opening. We got coverage in the Boston and Providence papers. Robert Taylor (Globe) did a photo and mention of the show. So, for a scruffy little alternative high school, we thought this was pretty terrific. I was a big fan, and I still am. I was friendly with Allan throughout his later life in many ways.

For at least the last 20 years of his life he was seen as the patriarch of Black artists in Boston. As far as I could tell, every Black artist in town knew and revered him. His life describes the stations of the cross of being a Black artist in Boston and America. He was seen and unseen, respected and disrespected. He was valued and devalued. From my point of view, he has still not been satisfactorily recognized. And aside from all that jazz, he was really good.

CG There is a show that opens this week at the private St. Botolph Club. It is being curated by Jean Gibran and she told me that she is getting some key loans from the Boston Athenaeum. Hopefully you will see the show.

(The club is currently closed and there are plans when reopened for limited access of nonmembers to view the Crite exhibition.)

AD I will.

CG As always it has been a pleasure to speak with you.

AD The feeling is mutual.

Postscript: Charles and I had this conversation on March 3, 2020, after the pandemic arose, but before it swamped us. Out of respect to all who now struggle with it – basically, everyone – I’d call these remarks a remembrance of things past and send wishes of well-being to all. AD