On the occasion of the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, seven Black artists were asked to respond to the theme of emancipation.

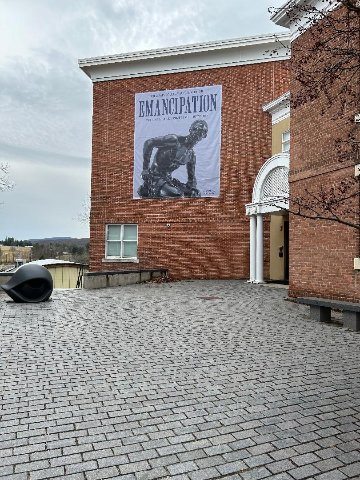

Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation at the Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA, through July 14.

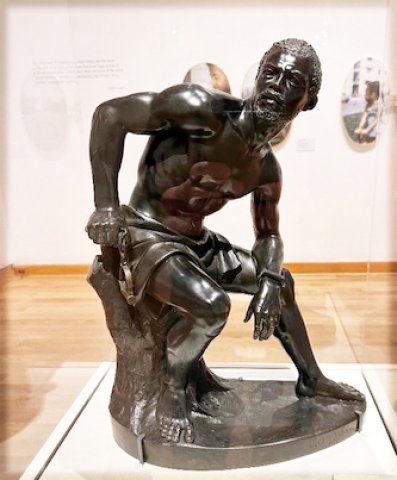

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Not long after that, John Quincy Adams Ward (1830-1910) created the bronze sculpture “The Freedman.” It depicts a semi-nude seated figure in the act of his removing shackles. Resembling the iconic Roman “Boxer,” the work was arguably the first bronze sculpture to depict an African American.

The piece, which was produced in an edition of eight, was remarkable for its humanity given it was created as the war raged on. Several years later, a group of African Americans commissioned a life-sized sculpture, but it had no say in its design. From its inception in 1876, Thomas Ball’s “Emancipation Memorial” has been considered to be degrading. The Black man, depicted as kneeling, appears to be anointed by Lincoln, who is standing above him. The statue was removed from Boston’s Park Square in 2020. Another version remains on view in Washington, D.C.

One of Ward’s sculptures is in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. Its curator, Margaret Adler, an undergraduate and graduate alumna of William College, was inspired by it to assemble the exhibition Emancipation. Conceived during the pandemic, the project was developed through zoom meetings with fellow curators Maurita Poole, director of the Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University, and Destinee Filmore of the Williams College Museum of Art. From a list of potential participants they made virtual studio visits with the following African American Artists: Sadie Barnette, Alfred Conteh, Maya Freelon, Hugh Hayden, Letitia Huckaby, Jeffrey Meris and Sable Elyse Smith.

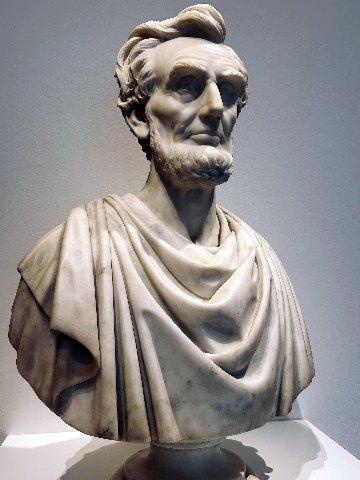

The WCMA is the third of four venues in which the exhibition will appear. The Williamstown installation has been enhanced with works from the museum’s collection as well as documents from the Williams College Chapin Library of Rare Books. These pieces include Sara Fisher Ames (1817-1901)’s marble portrait of Lincoln, a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation, and a pedestal-scaled version of Ball’s bronze sculpture.

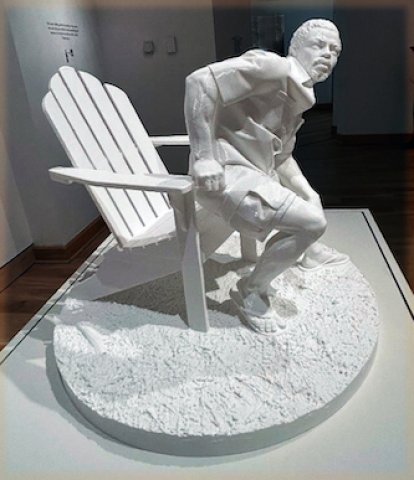

On the occasion of the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the artists were asked to respond to the theme of emancipation. This entailed contextualizing their work or creating new pieces. Adler’s pointed comment on Ward’s sculpture: “The piece wasn’t so much in need of remedying but an ‘unpacking’ for the present moment.” The difference between the Ward and Ball sculptures is striking; the contrast underscores an elemental point: emancipation was not bequeathed. This was not a gift bestowed by Lincoln, but rather making good on the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that “all men were created equal.” The curatorial mandate was to focus on the historic treatments of emancipation and liberation, or their lack. The work in Emancipation takes various forms — direct, oblique, and ephemeral.The most literal interpretation of the Ward sculpture was a 3D printed replica of the original by Hugh Hayden. The artist has modified the nude original in gleaming white plastic. This altered version features a man in casual attire, cargo shorts and flip flops, rising from an Adirondack chair. It evokes emancipation as leisure.

Jeffrey Meris’ mechanized sculpture exudes a horrific intensity. The figure includes a hydrocal plastic torso and the head of the artist. The dismembered body parts are embedded in what look like torture machines fit for Franz Kafka’s story “In the Penal Colony.” At half-hour intervals the kinetic sculptures are ground over an abrasive surface. The resultant dust is used in Meris’ large, multimedia, and abstract drawings.

The father of Sadie Barnette, an Oakland native, was formerly a member of the Black Panther Party. She made a request, through the Freedom of Information Act, and received redacted documents about him. Her installation of large works “FBI Drawings: Do Not Destroy, 2021” enlarge and reconfigure the pages. (Barnette’s decorative approach differs from the deadpan strategy chosen by Jenny Holzer in a show at MASS MoCA.) Here, texts related to the artist’s father were enhanced with glitter, roses, and faces from Hello Kitty cartoons.

Letitia Huckaby is represented by two recent series, “A Tale of Two Greenwoods” and “Bitter Waters Sweet.” Using photography, scraps of cotton, embellished flowers, and precisely positioned frames, these displays reference the communities of freed Black people in Tulsa, Okla. and “Africatown” in Mobile, Alabama. Tulsa’s thriving Black community was destroyed by white mobs in 1921. Photos of steps in demolished Tulsa homes are paired with shots of dwellings in Mobile. Images of descendants of both communities are conflated into the two series.

Maya Freelon’s interpretation of emancipation is obviously one of liberation, exuberance, and joy. The materials in her large installations “Fool Me Once” (tissue paper and adhesive) and “The Unfinished Project of Liberation” (tissue paper and ink) are the giveaways. She made the pieces with tissue paper scavenged from her grandmother’s cluttered basement, a homage to a trope of African American culture — recycling society’s detritus.

Forming a grid, large sheets are attached to a wall. Gallery traffic causes them to flutter enticingly. Some sheets are scrunched together, joined to form a large arc projecting from high on a wall.

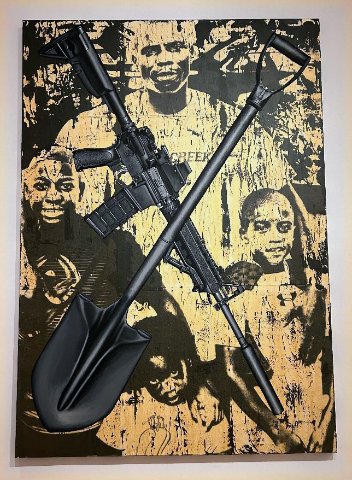

Alfred Conteh is represented by two works that differ in approach and medium: the painting “A Charge to Keep” and a life-sized figurative sculpture “Float.” While the pieces sit in sharp contrast, the pair is among the most galvanic in the exhibition.

In the painting, what looks like a collaged graphic background depicts a father and his children. In front of them hover — in an X-shape — large, super-realist renderings of a shovel and assault weapon. Conteh’s interpretation of emancipation is having the right to bear arms to protect his family and a shovel, which symbolizes the ability to raise food to feed them.

The sculpture depicts an expressionistic figure of a woman in eroded bronze. The gnarled, writhing figure is marked with stigmata — chains pull her down to earth. She is hemmed in by a cage that may represent the limits of her existence. Emancipation is not the term that best describes this work, rather, its opposite.

Sable Elyse Smith’s “Trappin 1” is make of of six giant “axes” from the game of Jacks. Each of the ends of the six jacks terminates in a round seat appropriated from a visiting room in a prison. This conceptual work, an assisted readymade, evokes the crisis of Black incarceration in America. It’s unlikely that visitors, without the help of reading the museum’s labels, will intuit that on their own.

Reposted courtesy of Boston's Arts Fuse