Conflating Lovecraft, Mugar and Houellebecq

iterary Sources for an Artist’s Work

By: Martin Mugar - Mar 18, 2024

Conflating Lovecraft, Mugar and Houellebecq

Literary Sources for an Artist’s Work

In literary tastes I was never a fan of science fiction or the horrific tales of Stephen King. Only Realism or so to say the focus on the depiction of the here and now captured my interest.

That is how I started my career as an artist as well. I used the tools of perception: value, color and perspective to create verisimilitude. I found that no matter where I was in time and space I could always set up a still life or pose myself in front of the landscape to find a story to tell.

The fact of the matter I have not read much in the realm of realism since college and since the 90’s most of my reading has been in philosophy. At first Nietzsche and Schopenhauer but by the late 90’s the French postmodern and its origin in the work of Heidegger totally absorbed me. The postmodern also had an influence on the art world in its making not just after the fact analysis. My reading of it gave me a linguistic handle on the kind of painting coming out of New York. Initially I had no idea that my blogging was coming to the attention of art critics.

I would write a blog and post it on other blog sites or email to friends. For a while, when it was a free ezine, I commented quite a bit on Hyperallergic. It was there in response to an essay by John Yau on a kind of abstraction coming out of New York that I came up with the moniker Zombie Abstraction to describe that art scene (None of the participants accepted the label). Several months later Walter Robinson on Artnet described the work as Zombie Formalism. Due to his establishment as an artist and art critic in the NY art world his labeling caught on and now ten years later AI gives him all the credit.

Except for several mentions of my role by Raphael Rubinstein I pretty much accepted being peripheral to the discussion. Followers on my blog pointed out that my writing had been noticed by the art critical community. First in an article Rubinstein wrote on French abstraction titled “Theory and Matter” in Art in America where he gave me precedence in coming up with Zombie Formalism before Robinson.

Now, many years later, an Italian PHD student who is studying the whole postmodern phenomena in painting for his PHD thesis and was quoting my work as source material. He pointed out a reference in an essay by Rubinstein to my blogging on the Italian philosopher Vattimo and how Rubinstein himself would have benefited from reading him due to the resemblance of Rubinstein’s notion of provisional painting to Vattimo’s “Weak Thought”.

In the essay He admitted to having heard of him second hand but only on my prompting did he read Vattimo. He agreed on the role Vatimmo could play in explaining Provisional painters and although he didn’t think the provisional artists were “weak” in any way. So, unbeknownst to me, my ideas had infiltrated the postmodern discussion and were having an effect on how it was being formulated.

Having a philosophical handle such as Vattimo’s “Weak Thought” was valuable in my encounter with second generation abstraction. Having a word like Nihilism that allowed me to find connections between Andy Warhol and Flannery O’Connor was indispensable. Words like that could label a whole generation.

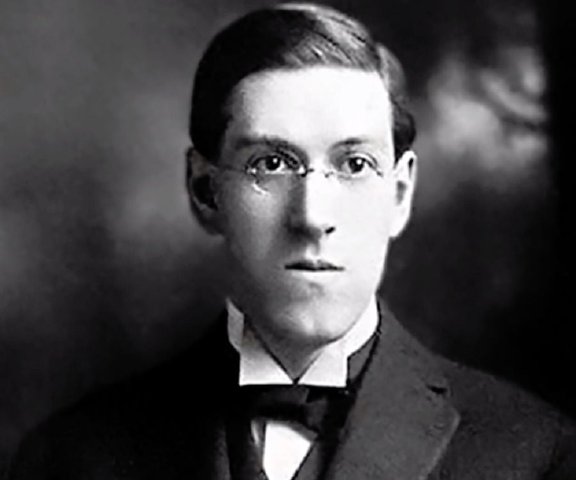

Lately, I find my own work beginning to make sense in the hands of the master of the macabre HP Lovecraft, who, like Stephen King, not someone I would go out of my way to read. But a series of encounters and recollections are beginning to haunt me and create a sort of nexus with the world of Lovecraft, a kind of hauntology to use a word invented by Derrida.

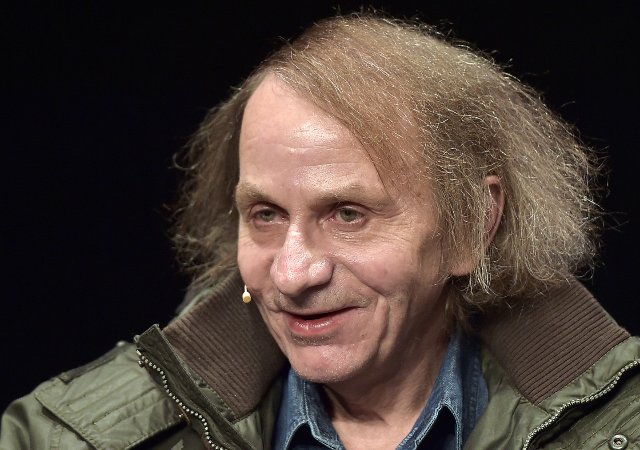

It started with a book on Lovecraft by Michel Houellebecq from the 90’s. I bought it already some years ago and it has been sitting on my desk, half chewed up by my dog, perused off and on until lately where I am now three quarters of the way through. I was surprised it predated his extremely popular fiction by many years and must have been formative in shaping his world view.

It appears the work was published to address the curiosity of a emerging interest in Lovecraft’s work and all things American in France. It included several of his horror stories. Just as Poe found more followers in France among the litterati than in the USA so it would be with Lovecraft. I had bought the book after reading Houellebecq’s “Elementary Particles” that I found interesting especially in so far as it resembled the nihilistic world view of Celine whose “Journey to the End of the Night” is up there on the top ten novels that I have read. The connections to my work I am still sorting out. Some of it is incidental. Considering that Stephen King provides an introduction to the book Lovecraft’s reputation in France was already cemented.

I read enough of Houellebecq’s book on Lovecraft to learn that the background of his work is 19th century New England but mythologized. It does not take long to peer behind the neologisms to get to the real places. One place that establishes the first connection to me is the world of Arkham that with some probing appears to be Salem, Massachusetts. A suburb of Salem is Danvers where a very gothic sanitarium was built and is referenced in Lovecraft's books. I remembered the building from my childhood as the mental hospital where my grandfather spent time as his health deteriorated. I have a distinct memory of his waving to us from his bedroom window as we left the hospital grounds. The hospital that was part of the skyline of Danvers seen from Route 1 has since been torn down.

“The Call of Cthulhu” is one of two stories included in the Houellebecq book. The monsters in particular Cthulhu are described in the contradistinction between their weirdness and foulness and the dour and puritanical New England scientists trying with their expertise to put a label on strange happenings that escape the normal events of the New England landscape.

It becomes clear that the monsters or “noxious” beings, as he likes to refer to them, are not divine and Houellebecq insists that they have a parallel existence in relation to us not vertically arrayed as in Christian eschatology but hidden since time immemorial disappearing from our world only to reappear at various times to disrupt the overly civilized world of New England. It appears that the civilizational edge was the border between New England and New York. His recollections of his first encounter of the New York Skyline defines for him the totally “other” as did the masses of immigrants that filled the streets as something he had a hard time identifying with. All opinions based on knowledge of his character point to a deeply engrained racism. Cthulhu and his minions appear for the most part to sailors who encounter them on the edge of the civilized world.

Lovecraft who wrote in the earlier half of the 20thc did not have much success with publishing his writing, but in the world of writers of the same ilk, he had a following as an innovator and mentor. No sooner did he pass away then the world “discovered” him and brought him to the attention of the general public. His notoriety began.

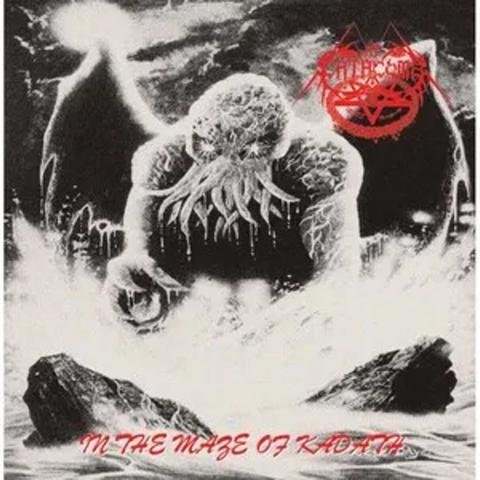

Oddly enough a world within which he has gained considerable fame is Heavy Metal music. Images from his stories appear on their posters and album covers. Considering his proud identification as a well behaved and well-dressed product of New England gentry his resurrection by head bangers is nothing short of bizarre. If you see the heavy metal crowd as wishing to tap into the formless hell that a character like Cthulhu embodies, or rather disembodies, then it all makes more sense. Their music’s goal is to terrify the audience. Lovecraft’s writing attempts the same with a repetitive incantation of adjectives that give a shape to a rather shapeless identity.

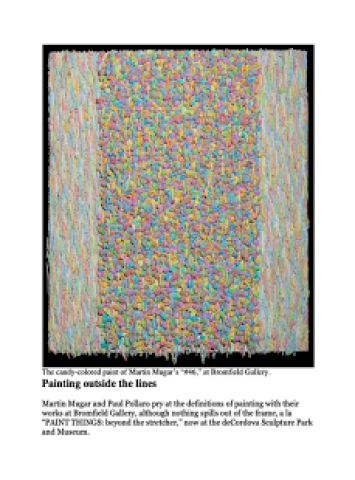

Finally I found that Lovecraft’s writing might explain a period of my work that I produced in the late 90’s into the first millennia. It got a lot of sympathetic coverage by the Boston Press especially numerous reviews by Cate McQuaid, from the late 90’s in Provincetown, into the first decade of the millennia in Boston. She seemed to understand why I was using three dimensional strokes and pushing beyond the limits of flatness.

That sympathy came to an end in 2013 at a show at the Bromfield Gallery with works that were much more obviously aggressive. She just said it all looked the same. Yet, before dismissing them she did notice something about the strokes that I only noticed recently in her review: ”Some of the strokes looked like sliding snails leaving their glistening tracks.” It was displeasing and in contradiction to her statement that it all looked the same. This organic reference is the direction I wanted to work to take. Also, I wanted the meaning of the painting to be embodied in each mark. Is this the first hint of the effect of Cthulhu? Ms McQuaid is obviously not a head banging metal head and would not take a conceptual leap with me to the next level I should say “Down” not up.

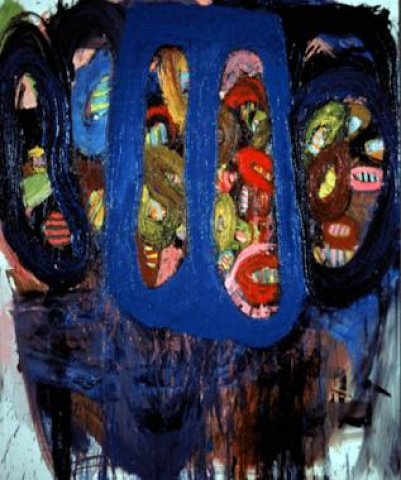

Dating from the mid- nineties this painting came straight out of my head. Strung the ellipses and filled them with stripes. I called it “Mulch” as the ellipses seem to be digesting the stripes. Another title is “Every Body is talking at me” from Nillson. It has a schizoid edge to it a reworking of a painting similar to the last one. A title for this could be "Mean Clowns" This is as close to Lovecraft as I got at this point in my painting. I think I titled this ”Footprints"

From a show at the Bromfield, around 2013, is where McQuaid stops enthusing about my work when she notices that my strokes look like the tracks of glistening snails.

This is another close up level of appreciation that does not translate on line when the work is seen as a whole. This is where the painting flips and starts to come out at the viewer. That probably has something to do with the liberating effect of the white canvas. Fairly recently, around 2022, spatially I started seeing strokes and drips as splashes.

Of course my painting is not in the realm of the noxious monsters of Lovecraft but the eventual push of the visual event off the surface seems to speak to a similar aggressive desire to reach out and engage the viewer. It also begins to abandon the pleasant color field that had dominated my work from the beginning of the millennium.