Report son Southern Africa: Part One

Soweto and Chobe National Park

By: Zeren Earls - Mar 18, 2008

Southern Africa: Part One

Since retirement my desire to travel annually to a distant land took me to southern Africa this year. My February birthday was the impetus for the winter break in a warm part of the world. I signed up for Overseas Adventure Travel's Ultimate Africa: Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe Safari trip. My previous trips with OAT had taken me into homes, schools, markets, providing cultural insights to the countries visited, therefore I knew this trip would be more than game drives. My friend Pat joined me on the tour.

The preparation for the trip was extensive. We were traveling to a malaria endemic area, which required special clothing that kept us covered, yet cool. Everything had to be light weight and/or in sample sizes, as our luggage allowance, including hand luggage, was only 26 lbs. due to light aircraft flights between countries. One of the most useful items I purchased was a travel vest from the National Geographic's catalogue. It weighed 8 oz. and had multiple pockets inside and out. We received a duffel bag from OAT, without wheels to keep the weight down.

On Super Tuesday, after casting my vote for the Massachusetts primary election, I set out for Boston's Logan airport on public transportation thanks to my light load. Checking my duffel bag all the way to Johannesburg, I flew overnight to London to catch my connecting flight the following evening. Fortunately, as part of our travel package, we had a dayroom at the Heathrow Hilton Hotel, where I instantly fell asleep upon arrival. My roommate Pat, who flew in from Washington, DC, arrived later, and had to tiptoe around not to wake me up.

Our British Airways flight from London to Johannesburg took eleven hours. I sat next to a South African man, who was on a three-week break following his three-week duty as supervisor on a flotilla for a French oil rig in the North Sea. He kept me entertained in between his sips of whiskey through the night. At 9 a.m., two hours ahead of GMT, we arrived in Johannesburg to a clear sunny day. Happily folding away the sweater I had on, I checked in our hotel at the Tambo International Airport until our departure for Victoria Falls the next morning. The afternoon was reserved for Soweto.

Soweto

Soweto (SOuth WEstern TOwnships) was an optional tour, which had to be pre-booked. I skipped the pre-trip extension to Kruger Park to be able to go to Soweto, as I wanted to see first hand the historic icon known for South Africa's major confrontations in pursuit of freedom. Four of us were picked up at the hotel by a local guide, who was a native of Soweto. During our 60 minute ride, he introduced us to his township of 4 million inhabitants consisting of poor, middle income and wealthy people, including several millionaires. Soweto has a university, a 4000 bed hospital, and a college for training jewelers. Although open to whites in principle, these institutions cater to blacks in this still largely segregated town. Many of its residents work in gold mines outside of the city, making the daily sweltering journey underground.

One of the residents walked us around a poor neighborhood. Women sat in yards shaded by shacks while children played nearby. Every garden seemed to have a corn patch. Billboards promoted condoms against HIV. We then drove through the sprawling city's upscale neighborhoods, passing by Archbishop Tutu's house and Mandela's former home as well as the one where he lived at the time of his arrest. He was in prison for 27 years.

In July of 1976, a student uprising against instruction in Afrikaans, which was not their native tongue, led to the killing of a 13-year-old boy, triggering riots. We visited the Regina Mundi (Queen of the World), the Catholic Church that served as sanctuary for many during the uprising and afterwards as host site for the meetings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Following the visit to the Hector Peterson Memorial, we spent the longest time in the Mandela Family Museum dedicated to the history of apartheid. Well worth the visit.

The next morning we transferred to British Airways for our flight to Victoria Falls, where we were welcomed by our trip leader, Mado, with a big smile. Dancers and drummers in native dress greeted visitors at the airport. From here we traveled by van to Botswana. As part of border control, we had to wipe our feet on a mat sprayed with disinfectant against hoof and mouth disease. Similarly, our van had to drive through a puddle of pre-sprayed water. On the way to the campsite, we saw storks on trees and cows by the roadside, while elephants with babies crossed our path. Spectacular clouds gave way to a quick shower cooling the air.

Chobe National Park

Chobe National Park is the first national park in Botswana. It was created by relocating the indigenous people, who had hunted animals for subsistence and for barter for European goods. Due to conservation efforts the animal populations have increased stimulating a vibrant tourism industry. Baobab Lodge on the outskirts of the park was our campsite. Upon arrival we were welcomed by its friendly staff with singing and dancing. They offered us cool washcloths and juice to refresh. We met the managers, the nature guides and the wait staff. Reflecting the rich local heritage, their names covered the full range from African to Western, including biblical, Kaho, Kelly, and Isaiah, to name a few.

Our rooms, called chalets, were round timber huts with thatched roofs. As protection from wildlife, we were told not to stray off the paths walking to and from the chalets and to always have staff escort after dark. The camps are owned and run by Wilderness Safaris as private concessions. The staff, including the cooks, is trained by Wilderness Safaris. Our dinner, one of many delicious meals we had, featured cream of sweet corn soup, roast chicken accompanied by potatoes, carrots, broccoli and salad. Over dinner the staff imitated animal sounds to acquaint us with those we might hear during the night.

The sound of a drum outside of our door was our wake up call at 5:30 a.m. Following a quick breakfast, which included sorghum porridge, we set out for our first game drive in safari vehicles. The full group of twelve, all dressed in earth tones to blend in with our surroundings, split up into two land rovers with a driver/guide in each. The basic rule of a game drive is to stay seated and calm in order not to distract the animals. Sudden movements and loud noises can scare them away or, in the case of elephants, encourage them to charge to protect their young.

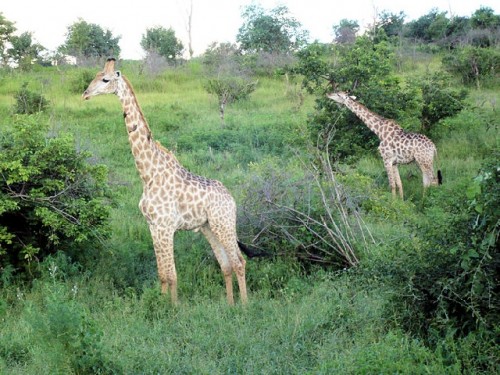

Our eagle-eyed guide introduced us to the wilderness as he drove. Paths with flattened grass signaled elephants nearby. African savannah elephants are big with curved tusks; the mother elephant always walks in front to protect her young. When they walk with their ears out, they are not dangerous. If they make a loud sound and the ears are flat against the face, they are ready to charge. We were the target of several mock charges warning us to drive off. Then, we got distracted by kudus, impalas and giraffes grazing along the roadside. Unlike the dry season, Savannah's lush greenery offered these animals plenty to eat. Kudus stood at attention with their ears tuned to catch any dangerous sound; slender impalas distinguished themselves by unique black-and-white stripes on the rump and tail.

Birds hovered above as we headed to the Chobe River flood plain. Among the easily spotted birds was the lilac breasted roller, the national bird of Botswana, distinguished by its sixteen shades of blue and thick beak for eating insects. Others were the European bee-eater, the fish eating eagle and the ground hornbills. Bovine cattle, chestnut red as well as jet black sable antelopes grazed in the open. We drove by baobab trees stripped by elephants drawn by the water in their fibrous wood. These trees are used to make floor mats, rope, paper and baskets from the bark, and they bear a fruit with white flesh used for producing cream of tartar.

After the morning game viewing we had a buffet lunch of beef lasagna, tuna mousse, sweet potatoes, broccoli, carrots and choice of sliced fresh mango, speckled melon or pineapple. Siesta time was during the heat of the day, followed by tea in the late afternoon. A treat was the basket making demonstration by three local women. A craft all women in Botswana must master by tradition, baskets are made by boiling, dying, splicing and weaving palm or baobab leaves. Bark or root dyes are boiled with the leaves for two hours to attain various colors. The women spread their wares over the lodge's long dining room table before us. The impressive display of baskets in various shapes and sizes was irresistible; I purchased one woven with dark leaves against light in a traditional motif.

The afternoon game drive expanded the morning's variety of animals: a dead porcupine on the road, its long black-and-white banded quills detached, grey warthogs with upward-curving tusks, baboons climbing trees, ambling giraffes with blotches of various shades, and majestic cape buffalos and bushbucks grazing near the water. A pod of hippos signaled their presence by creating bubbles in the river's surface. We waited patiently for a hippo to come up for air to get a glimpse of one of Africa's big five: Buffalo, elephant, hippo, leopard and lion. We returned to camp just before a thunderstorm, which lasted through the night.

Taking along a picnic lunch, we spent the next morning in our vehicles enjoying the park's variety of habitats and the various animals and birds attracted to its woodlands, grasslands and thickets along the river. In the afternoon a cruise on the Chobe River allowed us to view hippos and crocodiles close up. The river is a natural border between Botswana and Namibia. While the Botswana side is a national park, the Namibian side is tribal land, where poaching is allowed. Buffalos and elephants swim across the Chobe River from Namibia to Botswana to escape poaching. Chobe National Park is home to 120,000 elephants. Their growing number has been destroying the parkland, as elephants topple trees and strip their barks. Our day ended with an African braai (barbecue). In accordance with local custom, men were served first after washing their hands with water poured by women from a pitcher.

A lecture provided facts on Botswana. Centrally located in southern Africa, it is a land-locked country 23 degrees south of the equator. Slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Texas, Namibia lies to the west and north of the country. To the south is South Africa, to the east Zimbabwe and in the northeast Zambia shares a short border. It is a flat country mostly covered by the Kalahari Desert. Only 2% of the land is arable with 70% of it national forest. The majority of its 1.8 million population lives in eastern Botswana. Most of the food is imported. Setswana is the national language and English is the official business and written language.

The earliest modern inhabitants of Botswana were the San (Bushmen). They lived a hunter-gatherer existence in harmony with nature. They were displaced by the Bantu tribe followed by the Zulu. Boer Voortrekkers arrived in 1836 and drove 100,000 refugees to the arid northwest. In 1841 David Livingstone came from London to establish a mission school; by 1860 every village had a school. Sixty percent of the population is Christian; others are Buddhist or practice traditional beliefs. Ruled by local chiefs, the country became a British protectorate in 1885 and gained full independence in 1966. Since then the literacy rate has increased from 10% to 90%. The capital city is Gabarone.

One of the few countries in Africa to choose democracy over socialism, Botswana has inherited the British system of parliamentary rule. The head of state is the president who is elected to serve a term of five years by the 34-member National Assembly which includes the 15 cabinet ministers. The House of Chiefs is made up of 15 chiefs and tribal representatives who advise the National Assembly on proposed laws relating to land usage as well as social and traditional customs.

Botswana has massive diamond reserves that were discovered in 1967. It is the largest diamond producer in the world with an annual output of 20 million carats. Beside diamonds, gold, wildlife and tourism, cattle ranching and some manufacturing drive the economy. Despite the country's wealth, health care in general, and welfare of the indigenous population present major challenges. Forty percent of the country's population is HIV positive. 60,000 San people, who have lost tribal lands to national parks, are reeling from tremendous social and cultural change and live in poverty.

Our wonderful camp staff sent us off to our next destination with spirited singing and dancing.