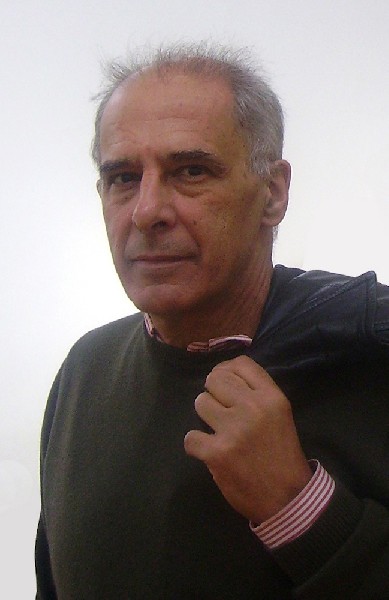

Looking Back with Global Artist Rafael Mahdavi

From Figuration in Painting to Abstract Steel Sculpture

By: Charles Giuliano and Rafael Mahdavi - Mar 10, 2014

Charles Giuliano Some years ago you were living in Wellesley with your then wife, Carter, a documentary filmmaker for PBS. Her late sister, Berkeley, our mutual friend was married to theatrical designer, Carl Eigsti, who you worked with building and painting sets in New York years prior.

You were commuting to a studio in the Marais and teaching at Parsons in Paris; spending weekends at a farm in Burgundy.

During a vacation week from teaching you were kind enough to let me stay in the loft. It was a great adventure and I came to know the neighborhood along the Rue de la Roquette, near the Place de la Bastille, the 11th arrondissement, which is near the Marais.

You bought it years before the Marais became fashionable.

When I stayed it was simple and romantically primitive.

It was wonderful to spend time in your studio and study the works in progress.

That resulted in our collaborating on an exhibition in 2000 for the Gallery of New England School of Art & Design/ Suffolk University.

You brought the large canvases from Paris in a tube marked ‘table cloths’ with no insurance evaluation. Which is how they were returned to avoid French custom’s fees. Our installer, James Manning, build stretchers for them. The show was in two venues. The paintings were in our gallery and I curated a related show of works on paper for the French Library. They published my essay in their magazine.

It was a great experience and I have always hoped that one day we would again work together. I have a wonderful work from that show, a large abstracted work with an image of a dog in profile. It hangs in our loft and is always admired by visitors.

From time to time you have sent me exhibition catalogues but there is much to discuss and catch up with. You always worked in sculpture at your country studio but now that activity has accelerated.

You are truly one of my most global friends. Your family heritage is Iranian, perhaps you prefer to say Persian. I assume that Farsi is among your several languages. I recall that your family lived in Spain and that you were educated for a time in Vienna.

Through all of that peripatetic activity you have focused on being an artist. For most of the past twenty years and more you had several exhibitions a year in as many nations and cities.

Can we start with a sketch of who and what you are. Just what does it mean to be multi-national, citizen of the world and artist?

What was the instinct that led to a life in the arts? Did you pursue this life and career with any sense of the difficulties that entailed?

It is interesting that I knew your work long before we met. The work continues to connect us over decades.

The first I knew of your work was through a piece that Berkley owned by her “brother in law.” It was photo based on canvas. Later you showed us a whole series of such works on paper in which you used mops to spread developer with experimental results. There was a freshness about that work that still resonates with me.

Rafael Mahdavi I was first home schooled by my parents in Mallorca until ten, then educated in boarding schools in London, Madrid and finished the last four years in Vienna. I graduated from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in January, 1968 with a BFA, then fled to Paris because I had been drafted.

Later as you know there was an amnesty. I became a French citizen in the nineties. I survived in Paris which is the toughest city. New York by comparison is a cake walk. I knew poverty in Paris and Rome.

I speak English, French, Spanish, German, Catalan and Italian--fluently. Now I am learning Greek.

I was ten years of age when I spent a year in Madrid and my mother took me to the Prado where I encountered the greatness of some painters, notably Velazquez and Goya. I still revere them. That year I returned again and again to the Prado, which I still consider the best museum in the world bar none. I squared off post cards of masterworks and copied them in pencil. Then I copied the masterworks in oil paints on canvas. I thought these masterpieces were part of the world’s furniture. These paintings continue generating profound meaning for me. I wanted to be guided by such masters, paint as well as they and like them leave my mark on the cultural continuum of my time.

Before the age of ten I wanted to become a bullfighter, as silly and banal as that may sound. As a kid I practiced with the village boys in Mallorca, and later in my early twenties I ran with the bulls in Pamplona. I became a so-called artist instead, which turned out to be less dangerous and less honorable than bullfighting.

I was not prepared for the years of hard work to master not only the craft of painting and sculpting but also––and perhaps more importantly––the craft of thinking for myself about art. It was difficult to figure out what was vitally important to me as a man and as a painter/ sculptor, that is to say, what was worth staying alive for.

Nor could I have foreseen the pettiness and hypocrisy that I would later discover in the art world. I was very lucky in that I met a few self-confident art dealers and collectors in New York, Madrid and Paris. In the seventies, eighties and early nineties a painter could still walk into a gallery and leave slides for consideration or even unroll some paintings then and there. Dealers had the courage to make up their own minds about whom to exhibit without the approval of flavor-of–the-month art world heavies.

I have become convinced through observation, reading and thinking that success––and I have had a modicum of success––in the art world today is based on luck plus ten thousand hours (Gladwell, Outliers) of practice prior to even trying to gain traction. There are practically no criteria left today for evaluating art. I know too many artists who are better than I am and have not gotten to square one because they have not had the good fortune to gain admission to the cliques of empowerment––most often defined by nationality, race, gender, sexual preference, religion, politics and raw cultural jingoism––that make up today’s art world.

CG The Dada master, Marcel Duchamp, early in the 20th century proclaimed that painting is “too retinal.” Since then there have been regular cycles proclaiming that “painting is dead” followed by yet another iteration of “long live painting.”

You have pursued a career as a painter and sculptor, often exploring figuration and representational imagery, but informed by all aspects of modernist and contemporary abstraction and experimentation with form and material.

Can we explore those parameters? How has the work been simultaneously traditional as well as informed by radical concepts and progressive agendas?

RM Before I get to the “retinal” thing and the development of my own work I want to say a few words about the Gegenrklärung, which in German means Counter-Enlightment. It was, roughly speaking, the movement glorifying irrationality and extreme subjectivity often associated with Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress), that morphed into the Romantic movement. It was spearheaded by J.G. Hamman and his student J.G. Herder who pretty much invented the notion of Volkskunst, i.e. nationalist or people’s art, an unhealthy idea to put it mildly. But above all it glorified the artist even if he was a mindless simpleton and that was yet another bad idea. It also favored the Romantic escapist ethics of accepting that the artist could be a child rapist by night and a sublime artist by day. I reject such ideas. Nobody should die for a comma or a color. The body is not indivisible and its movements and gestures make the work of art, from the synapses firing in the brain all the way to the hand holding the brush or the pen. There is no ghost in the machine.

Marcel Duchamp fell for the romantic ideology and backed into the notion that artists’ ideas or conceptions were ipso facto art because artists were brilliant and special by definition. The conclusion was that artists’ ideas were artistic. And the execution of these ideas was secondary. This opened the door for a lot of tomfoolery to parade as art. Duchamps’s ideas had little to do with art. They were at heart a meditation on ethics.

Claiming that painting is too “retinal” is like saying that music has too much to do with the sense of hearing, too aural. Painting, for those who have actually studied it, is damn difficult to do.

Painting may have “died” but once “dead” it became easy to make art and allowed for painters and sculptors to equate their creativity with thinking––without having to learn the craft of thinking. That’s like believing that because you shoot hoops on weekends you are as good as Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls or because you think once in a while you are the equal of Emmanuel Kant. All criteria went out the window. So, long live painting.

Thinking, like painting, is first and foremost a craft. You have to learn how to do it. Declaring painting “dead” rendered it not only easy but self-conscious. Great painting should never be self-conscious. You can’t paint well with history peeking over your shoulder. Yet much of modern art is not only self-conscious but pedantic into the bargain.

Painting should be more than pigment, color, optics and visual grammar. Painting about painting is as silly as writing about subjunctives and commas. Pursuing the literary analogy I will add that art like language, is by definition public even if all language to some extent undermines communication. Private language–– hermetic, incomunicado and incomunicando–-is an oxymoron as is the idea of personal or private painting. Great art for me is more impersonal than personal and therefore more accessible. Art is only worthwhile if it is shared. And it should leave people speechless.

Now, as to my work.

By the early seventies I had worked as a scenic painter and sculptor for opera, theatre, film and cabaret in New York, Paris and Rome, and had learned a variety of techniques for getting an image to work the way I wanted. These techniques were not always what you might call painterly but they were effective and in some ways helped me get away from the notions of paint and surface––which I found ridiculous––being bandied about by Clement Greenberg at the time. So I avoided the trap of painting about paint.

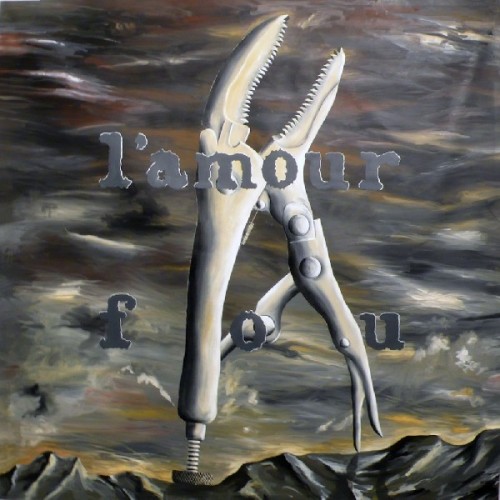

As I wrote in my artist’s statement for you when we first discussed this interview, my painting came into its own in New York in the early seventies. My work was about being somewhere as opposed to being everywhere or nowhere. No matter what happens, I told myself, I had my shoes, they were my real home. I painted them. I also painted black and white, grainy, arid landscapes, where I staked out my homestead with posts. I used my face as a landscape too, for that was a place that was surely mine. And I painted my few tools since they were my only possessions and they defined me. Tools have always had a sort of life of their own.

To save money on space and rent I painted on canvas stapled directly to the wall or the floor. I stored the canvases rolled up, transporting them was cheaper and I only stretched them on location for exhibitions. My relationship to my canvas was intimate and fluid like my relationship to my clothes and my skin and my guts. It greatly enriched the diversity of the means by which I applied and controlled paint. I still paint off stretchers today.

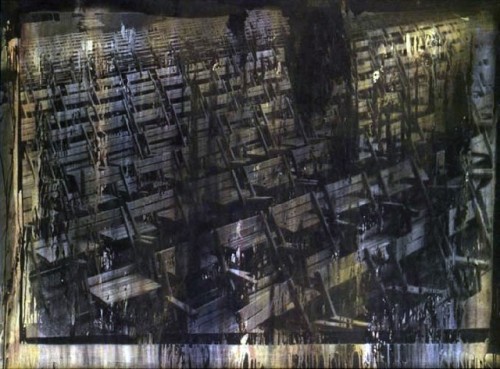

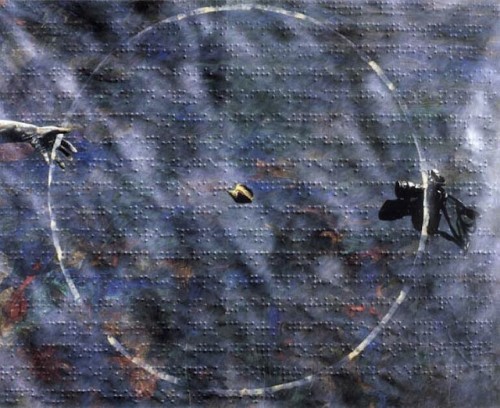

From the grainy black and white landscapes of my New York paintings, which resembled photographs, the move to photography in 1975 was seamless. I began doing photography in Paris and only did it for five years. Photography was faster than drawing or painting. I liked that and it was important for me if only to find out that darkroom wizardry and speed were not enough. I photographed empty outdoor cinemas and parks, and stage sets which I built in my studio. I printed these images on light-sensitive canvas, which came in rolls of ten meters long and one meter twenty wide. I solarized, “burned”, dripped, sprayed, and spattered the developer, stopper and fixer liquids. I also used my hands and my body, and mops and brooms to work with the liquids. Because of the large scale of these photo-canvases I had to invent certain technical tricks to print the images in my small darkroom. For shows I stretched the photo-canvases and avoided the costs of framing. The resulting work was hugely satisfying for me and, I am convinced, ahead of its time. I also painted on x-rays, which was a way of connecting, albeit too simply I suspect, with the body’s trauma landscape.

In 1980 I went back to painting, and for some ten years my paintings were large, intense, violent and colorful, navigating between the edges of realism, abstraction, and hallucination. In retrospect I think these works were influenced by my LSD trips in the early sixties.

As the nineties wound down I started to assemble a visual and symbolic alphabet, starting with my New York paintings: shoes as home, posts indicating a sense of place, the body as landscape. The broken sun-glasses stood for the idea that some images are shattering, the camera for painting’s nemesis, Braille for touch and blindness and seeing, water for the absence of taste and color, the dog for fidelity and poverty, the diver/leaper for the plunge into the unknown or the leap of faith, but not in the religious or Kierkegaardian sense, the circle for the eye’s iris and shells for a personal music, which is what you hear when you put a shell to your ear. Not the sea, but the music of your blood moving in your skull. From 2000 on I expanded my visual alphabet to include a house of cards, a labyrinth, a dove, an eagle, an infinity sign, and a paper airplane.

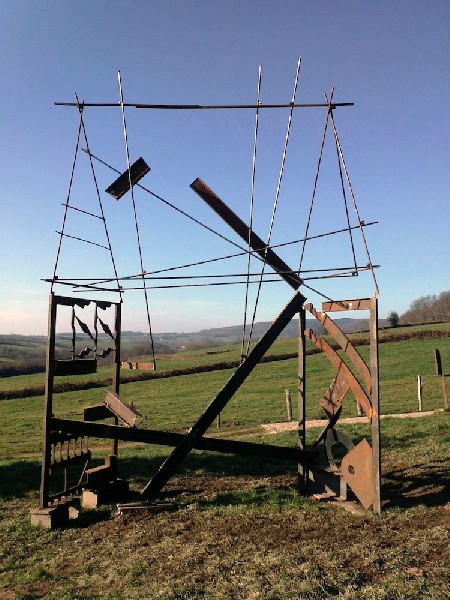

As to my sculpture, I will say that my hands-on approach to sculpture is crucial: I know what I make––an idea first formulated by the philosopher Gianbattista Vico. Sculpture is not an idea in my head but a physical thing. After working in clay, wax, wood and concrete, I gave up sculpture because I couldn’t afford it nor did I have the space to store the finished pieces. It was only when I bought a small farm in Burgundy in the eighties that I began to work in steel. I placed the finished pieces in the fields outside the house. The execution of sculpture in steel is physically tiring, difficult and at moments dangerous. Sculpture relates first and foremost to the human body and its unavoidable scale. Consequently, for me at least, sculpture, from the pyramids and the Panama Canal to jewelry and ploughed fields, is rarely abstract or cerebral in the sense that abstract painting is.

I keep returning to the one thing I am certain about: I have to paint about what is important to me, not what is expected of me. It took me quite some time to figure it out. I touched upon this already in answering your first question but I want to re-emphasize it. In our digital age it must be extremely difficult for art students to think and work their way out of the morass of information with which they are incessantly bombarded.

CG Update us on your current activities. At some point you sold the studio in Paris and moved full time to the country which has allowed for more involvement with sculpture. Discuss the works you are now doing in collaboration. Just how does that work? Who does what? In what sense is this mutually inspirational and satisfying?

Looking at your CV it is remarkable that you have had so many exhibitions, often several per year, over decades. What are the major museum and private collections that own your work?

We have now reached the legacy period of our lives and careers. It is when we organize, catalogue and think about the posterity of our creativity.

What are you doing in that regard? Are there retrospectives and catalogues in the works?

RM I sold the loft in Paris three years ago, retired from teaching at Pasons-Paris and moved to the house in Chalmoux, Burgundy, one hour south of Paris by TGV, where I have a painting studio and a metal shop, and some five acres of land for the sculptures.

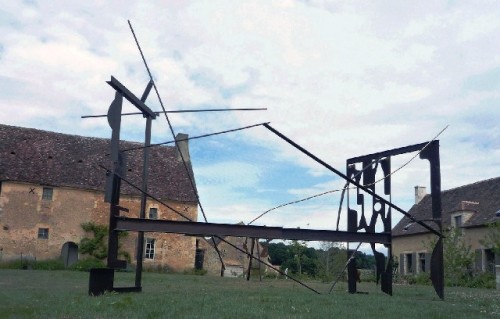

As to the collaborative sculptures over the last year let me begin by saying that I first met Jonathan Shimony, an American painter sculptor ten years ago when we were on the Parsons-Paris art faculty. We agreed on many aspects of making sculpture and shared similar cultural references. Jonathan now teaches at the American University in Paris (AUP). Two years ago we proposed a large sculpture for the 50th anniversary of AUP and Celeste Schenck the president of the university gave us carte blanche. The sculpture called Gateway was unveiled April 2013.

Jonathan and I discovered that we work well together. Since Gateway we have made two more large sculptures, Fallen Arms installed in September 2013 in Normandy for the paysagiste Phlippe Dubreuil, and La Quinta del Sordo (reference to Goya’s home outside Madrid: The House of the deaf Man) for a collector in Mallorca––this last piece to be inaugurated in May in the gardens of the Hotel Formentor. We are currently working on a piece in steel and glass for the Global Arts Pavilion in the Palazzo Bembo for the Venice Architecture Biennale, opening 5 and 6 June this year.

As mentioned previously the hands-on approach to the sculptures is important. Often present in our working method is David Smith’s idea of drawing in air, i.e. the notion that in sculpture a graphic look that generates meaning can be sufficient in a three dimensional work, as in La Quinta del Sordo.

When we built our first collaborative sculpture Gateway we understood that when making sculpture two brains and two bodies are better than one. We could move bigger pieces of steel around and our ideas ricocheting back and forth were complex, unexpected and open to questioning and reformulation. Each sculpture henceforth was a surprise in the sense that we began with an idea and ended up with something that neither of us had foreseen. We rarely work from models. Working together makes us question our esthetic assumptions and formulas, habits and preferences. There is a give and take and fortunately our egos our well anchored and do not come into play.

For our material we go to a huge steel dump, which luck placed 15 minutes from my studio in Burgundy. We load up the truck and back at the workshop we make the sculpture ourselves, that is to say we cut, drill, weld and bolt the sculpture together. If we are not going to paint it we take the sculpture outside the studio for it to rust in the fields for about a month. Then we coat it with a rust stabilizer.

Steel is the basic material in our work. It can be hard and delicate, rigid and tensile, demands real knowledge of techniques and basic electric tools and requires low maintenance once the work completed. We work mainly with plate steel of different thickness and shapes, I-beams, U-beams, angle iron and rods. We only do straight cuts with a cutting disc. Many of the elements in our sculpture are found and used as is. The finished sculpture can be placed indoors or outdoors. It must be stable, safe and weather resistant. Arc welding works with electricity, is relatively safe, not difficult to master and the welding machine itself weighs roughly ten kilos. Therefore we can work in the fields if need be. To a certain degree we build each piece taking into account the location site and its surroundings. For example Gateway was built for a narrow space and we added gold leaf in acknowledgement of the gold leafed Dome des Invalides close by.

Each one of us places pieces on the studio floor, changes the layout, makes suggestions, agrees, disagrees, cuts and spot welds. Slowly shapes and arrangements become defined. We lift up the pieces and look at them vertically, discuss them further and so on. We rarely talk about art while working. Our conversation ranges over large areas of interest to both of us, from philosophy to physics and more––and we laugh a lot, often poking fun at ourselves.

Once agreed on the final composition we decide what elements will be permanently welded and which ones will be drilled and bolted. This is important in dismantling the work for transport, either by a truck or in crates. Our outlook on the world is international.

Yes, I realize I have had many solo shows for decades all over the world. I have observed though that over the last thirty-five years there has been a progressive but definite shift from international markets to national ones regarding modern and contemporary art. The world may be a global village in commerce but the art world markets and museums, especially those funded by the state and run by cultural aparatchikis, have adopted a village or bunker mentality. Developed and developing countries have spawned local contemporary artists, which sell very well in their own country and are unknown and hardly ever marketable beyond their borders. There are a handful of exceptions of course but in general the era of the international contemporary art market is over. There is much more money in selling and buying national, not to say patriotic. I have been offered museum shows a number of times in different countries and the decision to show my work was overturned by cultural politicos who claimed I was too foreign or not local enough. So it goes.

I have three passports (USA, France, Iran) and a right to a fourth one (Mexico) and I do not feel that I belong to any one country. None of these nations has ever included my work in international shows. There have been two exceptions: Spain showed my work as a Spaniard in a five person group show in Asunción, Paraguay, inaugurated by the King of Spain, and the Global Arts Pavilion this year in Venice is a second exception and they don’t care what my passport is, which is refreshing. Since I belong to no country or minority you can understand that I am not often included in international shows. Private dealers and collectors do buy my pieces because they love my work and passion is universal.

I have never kept official track of collectors of my work. So, tugging at my memory, here are some: Grupo Serra Mallorca; Joan Guaita Collection, Palma; Museu Es Baluard, Palma; Cartier Foundation , Paris; Alain Perrin Collection, France; Ludwig Collection Budapest; BNP Collection, Paris; Chicago Art Institute, USA; Jedermann Collection, USA…

There have been four retrospective shows of my work: 1990:paintings 1980-1990 at Centro Culural La Misericordia, Palma; 1992: paintings from 1970-1975 at the Joan Guaita Gallery, Palma; 1994: photographic canvases 1975-1980 at the same gallery; 2009: paintings from 1970-2000 at the How Space Gallery in Quangzhou (Canton), China.

There is talk of a retrospective in Palma for my 70th birthday.

When I cleared out the loft in Paris I went through all my negatives and slides and kept those that I still found striking. I reread the hundreds of poems I had written since college and kept 45 of them. I translated them into Spanish and my art dealer Joan Guaita published them––along with ten photos from the seventies–– in a bilingual limited edition entitled Staying Alive/Permanecer en Vida. And I gathered up the pages of the autobiographical novel I have working on the last ten yeas. I will be done with that soon too.

Ah death…I have been thinking about death since the age of ten when I first went to boarding school. I reflect upon my end at least once a day, a rendezvous of a few minutes or more which keeps me on my metaphysical toes. I am an atheist so there is no comfort in any notion of an afterlife. As far as my creative legacy goes I have made no preparations of any kind. I don’t care what happens after I die. I want it all to happen when I am still alive and kicking. I only hope that after my death, in a best case scenario my children and my friends may profit financially from my works, and in a worst case scenario that they won’t be stuck with too much of my clutter.