Joe Thompson on Mass MoCA Expansion

Part One on Phase Three

By: Charles Giuliano and Joe Thompson - Mar 09, 2014

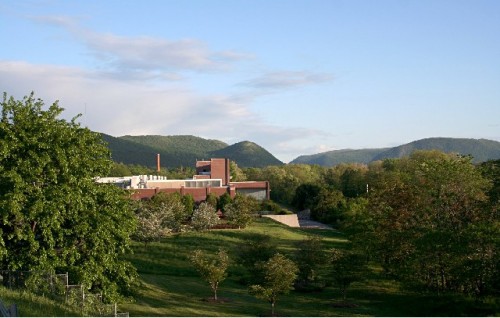

Several months ago we spoke at length with Joe Thompson about plans for the development of Building Six of Mass MoCA. At the time some $25 million for the project was a part of an omnibus bill for statewide projects. Now that bill has been signed by outgoing Governor Patrick and plans will be initiated. MoCA press release.

Charles Giuliano This is quite an adventure that you are about to embark on. (Link to initial report of museum development and expansion. In 2013 he discussed a Five Year Plan.)

Joe Thompson It’s part way there. As you know there are two key steps that have to happen. It’s the beginning but not quite a story yet.

CG Was it premature to put this out?

JT There was a vote by the house so we needed to explain the scope, intent and time line. The House voted to authorize funding which includes a line item for Mass MoCA. It now has to go to the Senate. If it’s amended it has to go to a conference committee for another vote. Once the omnibus capital improvements bill passes both houses which is weeks, or a couple of months away, it has to go to the Governor. But we’re well into it. We feel that we’re off to the races but it’s far from done.

CG What’s the feeling?

JT The House has done a lot of the heavy lifting. We’re hopeful it will move apace. That it will pass the Senate and get to the Governor’s desk intact. There have been three hearings on it to date. The big omnibus budgeting has been going on for six months or so in the House. This kind of legislation generally moves through the Senate a little quicker. It won’t be that long until we find out but there is still work to do. It’s a cautionary note to say we’re in the hunt but it’s not over yet.

CG Who have been your friends on the Hill?

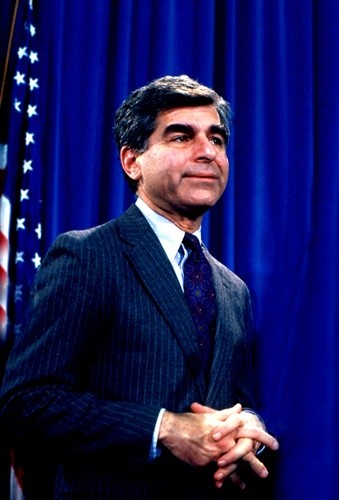

JT The stalwart work has been done by Representative (Gail) Cariddi. And Senator (Ben) Downing for sure. Mayor (Dick) Alcombright has been a staunch supporter. The Governor (Deval Patrick) has been encouraging.

CG Going back to the origins of Mass MoCA the original $35 Million from the Commonwealth took forever.

JT It was approved in March of 1988. There were feasibility and environmental impact studies. So money for that was released. But the first real money for construction didn’t flow until 1996.

CG Has all that money come to the museum?

JT It has. The first $18 million came for the first phase of the museum. Which opened in 1999. With about 200,000 square feet renovated. The remaining $17 million came in bits and pieces over the next ten years. As we added on buildings and did renovations. We were matching that money with private donations all along. The last of that capital grant was expended by 2000.

CG At the time that $35 million was shocking, controversial and unprecedented. Now, fast forward in time and we are looking at $25.4 million all in one blow.

JT Yeah. But $35 million in 1988 would be close to $65 or $70 million in today’s dollars. While $25 million is very significant in terms of apples to apples it’s about a third of the real economic value compared to the original grant.

CG Then and now the average man on the street is saying why are my tax dollars being spent on an art museum when we need roads, bridges and help with schools? How has the museum managed to leverage through those grass roots obstacles?

JT It’s about a return on investment for the state. This is part of a $1.2 billion dollar capital projects legislation that included many roads, bridges, schools and theatre renovations. All across the state.

CG So this is a part of a larger picture.

JT Yes. (Pauses to consult data and calculates.) This is about 2% of the total capital improvements bill.

CG Is this taxpayer’s money?

JT If the state approves and does them all they will issue bonds. Thirty year bonds at $1.2 billion and pay them back. The state bonds the money and pays back. We would get $25 million to put into the buildings. It would come over two or three years. We would have to raise some $30 million to complete the capital improvement to the buildings. Also to create the building reserve funds; maintenance endowment and money to pay for heat and gas bills forever on these buildings. We’re taking on the obligation to take care of the buildings.

CG What is the degree of difficulty in raising $30 million?

JT It will take two or three years of work. We will be approaching all of our supporters who are near and dear to the project. Starting with our board. We expect to reach out to 300 to 400 individuals. It’s a lot of work.

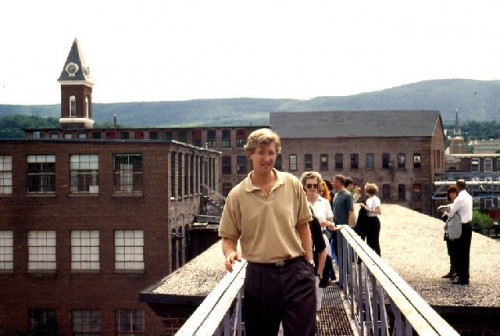

CG In a sense Mass MoCA has shadowed our lives. I include myself as well as you. For me it started when Tom Krens met with me for lunch and then took me back to his office at the Williams College Museum of Art. He showed me charts and diagrams that you once told me you had worked on. After Tom left I was later part of a media group that came for the weekend hosted by the Clark and first met you. I recall a tall bean pole with glasses.

JT Exactly.

CG You took us through the buildings. Now, these many years later, this has literally been your entire professional life.

JT It has been. We are coming up on year 26. (Thompson on 25 years.) It’s the 15th year of the museum as an operating institution. As you know there were twelve years before that of planning, tin cupping and preconceiving. We were trying to put Humpty Dumpty together again. (Both laugh) So yeah coming up on three decades.

(When Krens left to become director of the Guggenheim the Mass MoCA project was just about dead in the water. Krens continues to take credit for founding the museum. It’s true that he initiated the project but it was Thompson who brought it back to life. For more than a decade he and a core of associates worked virtually pro bono to sustain and eventually launch what is now a well established and thriving museum and performing arts center. C.G.)

This (new) project doesn’t happen over night. First of all the money hasn’t been approved. We have private money to raise. Then there’s architecture to do. Demolition. Cleanup. It will take years to do and we will be well into the start of our fourth decade by the time all is said and done.

CG In the museum field it is unprecedented that one would have lifetime tenure with a single museum. In the beginning it was non existent and insignificant.

JT A figment of our imagination.

CG Now it has evolved into one of the most important museum positions in America. It’s a leap of faith to go from Williams College to where we are today. Can you respond to that emotionally?

JT There needs to be a certain amount of naivety and stubbornness. (Both laugh) To take on something like this. It’s not the kind of project that people at the middle or end of their careers take on. There are reasons why startups are often done by younger people. Maybe it’s unusual to stick around so long. Mass MoCA was never complete. It’s still not. Even when this is done it won’t be quite. We’re calling it the Final Phase. That’s not quite true. Even when we’re done there will be another 35,000 square feet of buildings to be developed. There will always be more work to do.

CG We’re mortal. At some point there will be a legacy to pass on. Whoever becomes the next director will have enormous shoes to fill.

JT The great thing about contemporary art museums, which you know because you’ve watched it and written about it, is how the world keeps changing. The roster of artists who are defining our times is always changing. It’s an inherent advantage of having new blood. You assume that new blood comes with fresh eyes. They are closely attuned to what’s going on now. Yeah. I’m probably getting long in the teeth for this job.

CG Going back to Tom Krens he had two protégées. You and Michael Govan.

(He is the current director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Born in Washington D.C. in 1963, he graduated from Williams College, with a B.A. in Art History. Prior to becoming the director of LACMA in 2006, Govan worked as the director of the Dia Art Foundation in New York.)

He moved on. You never left home. In fact you are within bicycle distance of your Alma Mater. That’s rather astonishing.

JT It is funny.

CG Mass MoCA is often compared to Dia Beacon in New York and the Chinati/ Judd Foundations in Marfa, Texas. We have visited both and because they are mostly fixed permanent installations there is not a great incentive to return. Although thriving and expanding arts communities have been established because of them. The original plan of Krens for Mass MoCA was similarly to be a low maintenance warehouse for minimalist works. Initially he was negotiating with Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo to bring his renowned collection of minimalism to North Adams. That didn’t happen.

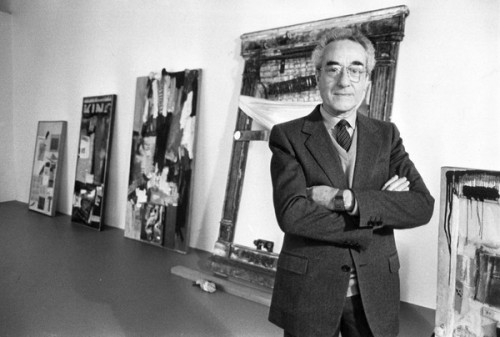

(Count Panza died at 87 in 2010. Over the previous 30 years Panza had acquired nearly 600 paintings, sculptures, installations and mixed-media works by Mark Rothko, Robert Rauschenberg, Bruce Nauman, Robert Irwin, Maria Nordman, Dan Flavin, Richard Serra, Hanne Darboven and about 60 more -- a few European, but mostly American Abstract Expressionist, Pop, Minimal and Conceptual art. Many of the artists worked in Los Angeles – Robert Irwin, Bruce Nauman, Nordman, Larry Bell, Douglas Huebler, James Turrell, Doug Wheeler. In 1984 he sold 80 Abstract Expressionist and Pop works to L.A.'s fledgling Museum of Contemporary Art, where he was a trustee, including paintings by Rothko (7) and Franz Kline (12) and mixed-media sculptures by Rauschenberg (11). Between 1990 and 1992 Krens acquired 350 works from Panza for the Guggenheim. These were essentially the works that he had planned to “warehouse” in North Adams.)

JT The original idea for Mass MoCA got built and it is called Dia Beacon. It’s Apollo vs. Mass MoCA as Dionysus. By which I mean a beautifully conceived, beautifully lit, perfectly proportioned box. Which becomes a fixed monument to works of art of a certain period. Such as European and American minimalism of the late 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. That’s a bit of a simplification because the Dia of course does do changing exhibitions. More all the time. Nevertheless when you think of that institution you think of an exquisite box. It’s fixed in time and when you go back and visit it’s largely the same. There are a lot of people who go back but not quite as many because it doesn’t have a changing roster of exhibitions and performing arts. It has a completely different vibe. That said, if Dia and Chinati are a series of boxes then Mass MoCA is more of a platform. New work gets made and new performances evolve from residences. There are works of art literally coming into being here.

CG As I understand plans so far for the 120,000 square feet of new exhibition space being developed a lot of it seems modeled on the Dia/ Chinati idea. With loans on view for 25 years or so.

JT That’s a very good point Charles. We have thought a lot about this. In part it is powered by the beauty of the LeWitt installation. And now the Kiefer installation. If you think about your favorite museums they have changing exhibitions built around a core of great moments in art history. Works that you like to return to year after year. I’ll go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see whatever spectacular exhibition they are featuring. When I’m there I always return to see Duchamp. Those deep important collections.

Until LeWitt and Kiefer Mass MoCA was always as good as its last show. Sometimes you hit it out of the park and other times you don’t. Your reputation rises and falls. It’s up and down. We always feel we’re doing the best possible shows. You look back and say, that was a winner, or oops, maybe that was a double. The most lasting and powerful institutional model for museums is to do both. Your great core collection is protons around which your special exhibitions and performing arts programs can twirl like electrons.

CG When you opened Mass MoCA it followed the form of a Kunsthalle. Which in the European model is an institution that exhibits but does not collect. This allows for freedom and flexibility. As you stated being only as good as its latest exhibition.

A classic example of this is the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

(The Institute of Contemporary Art was founded as the Boston Museum of Modern Art in 1936 with offices rented at 114 State Street with gallery space provided by the Fogg Museum and the Busch–Reisinger Museum at Harvard University.The Museum planned itself as "a renegade offspring of the Museum of Modern Art", and was led by its first president, a 26-year-old architect named Nathaniel Saltonstall.)

During its long and complex history it never collected until recently when it moved to its new location on the Boston waterfront. Since the Museum of Fine Arts had only tepid interest in modernism and the art of our time the decision of the ICA not to collect may only be viewed as significant and continuing loss for the culture and reputation of the city.

(On the outskirts of the city is the renowned contemporary art collection of the Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University which was established by founding director, Sam Hunter in the mid 1960s. There were threats to close the museum and sell the collection but that has passed and there is a new direction for the Rose.)

While the new ICA has been praised for its design, now that it has decided to collect, the land locked museum has run out of space adequate to show and store a growing permanent collection. Unlike the fortuitous Mass MoCA (25 buildings on 16 acres) there is no possibility for expansion. In addition to their new jewel box home they should have acquired relatively cheap warehouse space as an annex. Similarly when the Berkshire Museum was undergoing a $9 million renovation I asked then director Stuart Chase why he wasn’t considering picking up some cheap, readily available downtown real estate. The Berkshire Museum is currently undergoing more internal renovation.

In the long run the concept of reuse architecture (Mass MoCA) has more sustainability. Long term the ICA has made a fatal error in not picking up cheap additional space for future needs.

Ironically, the failure of North Adams, when Sprague Electric left the city, has proved to be a long term cultural boon. Phoenix like it is rising from the ashes.

Now some 15 years into being operational, it is interesting that in this next Phase Three MoCA is shifting from being strictly a kunsthalle to evolving into being a museum. Even though what will be shown are 25 year loans and not acquisitions. MoCA does not “own” its Kiefers and LeWitts.

JT We have many of the benefits of a core quasi permanent collection. In my view we avoid many of the liabilities as well. Once you own works you have the responsibilities of conservators and registrars. You become about preservation. Whereas if you team up with people who own those works they retain those responsibilities. In the case of LeWitt Yale University is doing the archiving work. The resources that takes remains with somebody else and allows Mass MoCA to keep doing what we do. What we do best. Which are temporary exhibitions and large commissioning projects. Performing arts residencies. It allows us to keep our focus on that.

There is some magic in that. I also like that today, when there are so many points of view in the world. People have so much ready access through writers like you and others to what’s going on in the world, that, to have a place like Mass MoCA, where there can be, side by side, four or five or six curatorial points of view. We have ours. There’s the LeWitt/ Yale take on the world with Sol LeWitt. There’s the Hall Art Foundation take on the world with their devotion to Anselm Kiefer.

If we can build a (new) space that allows for two or three or four more of those partnerships then Mass MoCA becomes a museum that has four or five voices within it. Four or five points of view. It becomes a campus of museums. That is more interesting for visitors than one point of view. A multiplicity of voices if far more interesting. You get conversations. There are debates. To me it feels more contemporary.

(At Chiati Foundation, in Marfa, Texas touring building after building, as well as his home and studio which is open one afternoon a week, there is no such dialogue. The entire vast project is dominated by the work of Donald Judd and his colleagues like John Chamberlain and Dan Flavin. There is only a tiny increment for evolution and change. Over the coming decades it will become ever more quaint and stagnant. C.G.)

CG Speaking personally, this is my opinion as a critic, to me your greatest accomplishment has been the exposure of Asian artists.

JT We’ve done a lot of important work on that.

Occasionally we do big projects with very well known artists. The soul of our work, if you take a look, is with artists in their 30’s and 40’s, who have had maybe small museum exhibitions or have been in group shows. They are ready for a larger and more sustained solo exhibition. We have given them space and time. We are a place where mid career artists can explore ideas that are bigger and more sustained than they might otherwise be able to do. That’s what we feel. We often give them time and fabrication and rehearsal resources.

As you know we often do very young artists. They may only barely have gallery representation or none at all. We’re not scared about that.

Typically it’s more people who have been at it for ten or fifteen years who have a body of work. They are respected and have been written about. We give them a chance to do something bigger, newer, whatever.

CG Let’s project forward and assume that Phase Three does get done. We are looking at that space. You have said possibly two or three long term installations. Does than mean individual artists along the line of LeWitt and Kiefer?

JT I think it’s a combination of working with individual artists and working with foundations and institutions that are interested in what’s on offer here.

We have a healthy and growing audience. These are people who are interested in seeing new work.

Thompson Part Two.