Insider’s View of the Protests Against the MFA’s ‘Boston Masssacre’—1999

Adapted from Forthcoming Book

By: Patricia Hills - Mar 03, 2025

[Adapted March 3, 2025, from manuscript of forthcoming book, Feisty Feminist Challenges the Art World.]

© Patricia Hills

“What’s past is prologue”

William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 2.

Already in the late-1980s and 1990s we saw the trend toward top-down control by many museum directors emulating the corporate model and moving away from the collaborative approach in which directors allowed their curators to make curatorial decisions. Moreover, because of the challenges of government and corporate censorship—often in response to what curators were doing—directors became anxious about the cuts in funding, sought to appease the politicians and diminished the independence of curators. [See Chapter 19]

At the same time museum trustees began looking for a new kind of director. Instead of art history people rising through the curatorial ranks, the new directors often had MBAs and were fully in step with the corporate models. Directors were now called Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) assisted by the Chief Financial Officers (CFOs). Of course, some directors relished the tactics of corporate total control because of their psychological need to be perseived as being on top of their game, when, in fact, powerful insiders on the boards of trustees and CFO’s were increasingly writing the script.[1]

One example of what I call “governance overreach” occurred in the summer of 1999 in Boston with layoffs at the Museum of Fine Arts of eighteen professionals—including many top-level curators and administrators respected in their fields. The MFA also hired twenty new staff, which tells us that the MFA trustees ordered the firings not just for financial exigencies but because of their need to replicate a corporate model. This model was not adverse to mass layoffs to boost that exercised mass layoffs to boost efficiency and to maintain profits.[2] Lay-offs were then in the news. Indeed, layoffs in industry in 2000 affected 1.2 million workers.[3]

Museum colleagues across the country were shocked at the MFA’s swift firings. They had all taken for granted that they belonged to a profession with secure jobs because of their expertise, their smarts, their imaginative projects, and their connections to networks of artists, academics, and patrons. Moreover, they were willing to work long hours for pathetic pay checks. They compared themselves to academics with written tenure contracts, even though tenure was not an actual perk of museum work. Museum staff members working for government-sponsored museums, then felt secure of the fact that they had government jobs.

In retrospect, this change at the MFA in 1999 toward the top-down corporate model of mass firings of knowledge workers presaged the early months of 2025. This was when workers in the knowledge field—the arts and the sciences—were indiscriminately fired with no acknowledgment of the special skills they have to make us safe, well fed, healthy, housed, educated, and enriched by the arts.

Returning to 1999: The layoffs seemed to me, and others, based on Rogers’s personal need for control. Moreover, he seemed to be indifferent to how much the top-level curators had brought to the MFA in terms of raising money, cultivating patrons, and overseeing cutting-edge scholarly research. I found myself leading the protests against the layoffs.

So, let me tell my side of the story.

Rogers, formerly Deputy Director at The National Portrait Gallery in London in the mid-1990s, accepted the MFA’s offer of the directorship after, it is rumored, he had lost his bid to become the director of the Portrait Gallery. To Bostonians he was urbane without being stuffy, seemed responsive to the community, and had a lovely, resonate British accent.[4] He clearly was geared to take his marching orders from MFA trustees such as Edward Johnson, the head of the very successful Fidelity Investments.

Critic Charles Giuliano, who has made a detailed study of the MFA, succinctly states the situation leading up to the hiring of Rogers. “During an economic downturn the museum had fallen on hard times under prior director, Alan Shestack, who served from 1987 to 1993. [The director] was given a broad mandate to kick-start what had become a moribund institution.” In 1991, as a consequence, there were broad layoffs “to trim $1.7 million off a projected $4.7 million deficit. Forty-two positions were affected, and 21 people were laid off. The MFA had borrowed an estimated $6 million to $10 million from its endowment, which had decreased to $145 million. . . . More cuts and shakeups would follow.”[5] Indeed, they did.

Fast forward from 1991 to 1999: The financial situation still remained as a problem for Rogers—solved by a further reorganization no doubt dictated by the trustees. It was Rogers, probably in collaboration Johnson, who advanced the “one museum” slogan, which meant that the director would actively focus his energies on all aspects of scheduling, curating, and managing exhibitions and loans, with little input from curators other than their writing wall labels and entries for exhibition catalogues. In other words, curators were becoming “content providers” rather than true curators.

On Friday, June 25, 1999, the eighteen fired employees included Jonathan Fairbanks (The Katharine Lane Weems Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture) and Anne Poulet (The Russell B. and André Beauchamp Stearns Curator of European Decorative Arts). Rogers also fired other high-level administrators. Most of the staff (and we outside academics with connections to the MFA) interpreted his actions as a way to humiliate the professionals and instill fear in the minds of other museum staff.

That summer day Rogers called the individuals into his office, fired them, and told them they had to clear out their offices, turn in their keys and badges, and vacate the Museum before the end of the day. Although there had been rumors earlier in the week that Rogers was up to something, the targeted staff were blindsided. They had not been previously consulted about such a “reorganization,” and there had been no indication that firings would happen. Those fired were escorted back to their desks by security guards. Fairbanks, a 28-year veteran of the MFA, told Rogers, “I don’t need the guards. I know where my office is.”[6] When Fairbanks returned to his office, his computer had been disabled—which also had personal emails and private papers. Museums, usually genteel institutions, had never treated high-level staff so outrageously.

Rogers was no doubt charged to act by the Trustees many weeks or months before. Although he justified the purpose of the firings as the “restructuring” of the MFA, what was clear to most of us in the field was that Rogers resented the independence of the long-term curators, such as Fairbanks, who raised his own funds to purchase artworks. Fairbanks’s special group of collector/patrons, “the Seminarians,”[7] remained loyal to him. He was known internationally. His department had long been considered the flagship for the study of American decorative arts.

Rogers merged the American Decorative Arts and Sculpture with American Painting to create one department. Curator Theodore Stebbins’ job was expanded as he took on new responsibilities as the “Acting Director of American Painting and Decorative Arts.” He tendered his resignation about three months later in protest against Rogers’s clear intentions to control all aspects of the planning, curating and managing of the upcoming new “American Wing.”[8] When curator Anne Poulet was fired, her European Decorative Arts department merged with European Painting. Poulet went on to become the director of the Frick Art Museum.

The Boston press ran articles and editorials deploring the event. Even the respected Burlington Magazine ran a long article questioning Rogers’s skills as a museum director and his actions. Christine Temin wrote a lengthy article for the Boston Globe on July 26, page E3, in which she quotes me saying the following:

“I see two issues here. One is Malcolm Rogers firing a curator like Jonathan Fairbanks, who built a department and has been collecting extremely knowledgeably. [Rogers’s] treatment of him has been outrageous. The second issue is policy making at the top and proletarianizing your professionals. The independent voice of the curator disappears. Museum directors now are micromanaging, making decisions based on advice from financial officers and marketing departments. The trend among directors like Malcolm Rogers is to be in complete control.”

Besides my words here, I also wrote a sharp, short piece, “The Boston Massacre,” published in Art New England.[9]

I didn’t just raise my voice to the press, I also directly participated in agitation. On July 15, I sent the news about Rogers’s handling of the firings to the American art list-serve [Amart-L], which serves hundreds of art historians across the country. I urged the list-serve readers to write letters to both the MFA Chairman of the Board of Trustees as well as its President, whose addresses I supplied.

Not surprisingly there were counterattacks from the Rogers forces. A person named Barbara Warren wrote to Jon Westling, then President of Boston University, and enclosed a printout of the two pages of my July 15 list-serv email. Excerpts from Warren’s letter follow:

“I am writing to you in response to an E-mail that I received last week regarding the restructuring and layoffs of the Museum of Fine Arts . . . that originated from one of your staff members, Patricia Hills. . . . I felt that I had to comment on her lack of judgement [sic].[10] . . .

“I am both appalled and surprised that Boston University, a public institution, would countenance the use of its e-mail internet services for the purpose of criticizing and second guessing the policies of the Director of the Museum of Fine Arts . . . . How the Museum of Fine Arts chooses to operate should not be the business of BU or its staff. . . .”

She then continues: “At the time Malcolm Rogers was hired as Director, nearly five years ago, the place seemed to ’lack spirit’ and was stagnating. . . . There must have been some very good reasons for the decisions that he and his trustees made regarding the latest restructuring. Perhaps Ms. Hills should have found out what really happened before sending out her ill-advised and damaging memo.” Her letter was cc’d to Malcolm Rogers.

President Westling replied on July 30, politely thanking Barbera for her letter and adding:

“Please be advised that Patricia Hills is not one of my staff members but a professor of art history. Boston University is not, as you put it, ‘a public institution,’ but a private university. We do not censor our faculty members’ mail or attempt to control their expressions of opinion. As far as I can tell, Professor Hills acted within the bounds of academic freedom in writing to you and others about the recent dismissals at the Museum of Fine Arts.

“You observe that Professor Hills sent her message via a list-serve and through her Boston University e-mail account. You are wrong, however, to infer from her use of her University e-mail account that Boston University endorses the substance of Professor Hill’s [sic] statement. Boston University has taken no position on the MFA dismissals….

On the question of whether a university should ‘countenance’ a faculty member in art history expressing views . . . about the policies of the Museum of Fine Arts, I must admit that your objection astonishes me. You may disagree with Professor Hills professional judgment, but to object to her right to express that judgment is surely counter to the spirit that ought to animate both Universities and art museums.”[11]

His letter was cc’d to both Rogers and me. Of course, Westling did not “fire” me.

Public response to Westling’s letter was picked up by media people, who somehow got hold of copies of the letter. Hilton Kramer, a critic who once slammed my Whitney exhibitions, wrote in praise of Westling for defending my academic freedom.[12] A reporter for a Boston neighborhood newspaper, The Beacon Hill/ Back Bay Chronicle went digging into who was Warren and what might be her motivations for writing a letter complaining about me. [13] The reporter somehow unearthed the complainer’s occupation: “an employee of Crosby Advisors, part of Fidelity Investments.”

I switched into high gear. My primary activity for the summer of 1999 then became collecting the carbon copies of protest letters written by directors, curators, and university people connected to the museum world. These letters from Fairbanks’ supporters had been sent to the Director and the President of the MFA, with carbon copies going to Fairbanks. I also received emails from my own colleagues in the field. One eminent curator responding to my email said: “I am horrified by the MFA's action. As I immediately wrote Jonathan, he did exactly what curators were supposed to do and did it the best. I've known him since 1971. Among his other legacies is the series of North American Print Conferences which have spawned the best research and writing on American prints.”[14]

I took the copies of the protest letters and photocopied them into large stacks. Fairbanks’ daughter would then mail them in batches (there were four such batches) to all the members of the MFA’s Board, since we were convinced that neither the Director nor the President were sharing their letters. The fourth batch we also sent to the “overseers.” There were many more than a hundred letters, including an enthusiastic letter from the television star and art presenter Sister Wendy.

For the cover letter to my second batch I pointed out the response of Ivor Nöel Hume, a leading colonial archaeologist. He wrote of the firings that had happened at other institutions and commented that such “manufactured attrition . . . has left the surviving staff in a state of constant fear—none knowing whether next Friday may be their last day of employment. Therein lies the tragedy of such Draconian policies. They not only hew away at scholarship; but in the process destroy the morale of the survivors.” Hume ends by saying: “Directors are appointed whose expertise goes no further than ledgers and turnstiles, and in consequence pandering staffers with P. T. Barnum mentalities stoop lower and lower in their attempts to reach new audiences. They are purveyors of what a cynical media calls edutainment, in whose cause truth all too often is slowly generalized away until only the glitter remains.”[15]

In my letter I followed Hume’s comment with my own: “In my opinion (which I share with many of the letter writers), the firings, the method of the firings (eight hours’ notice) and the direction that Mr. Malcolm Rogers seems to be taking the MFA are wrong. Museums are not ‘corporations’ in the sense that Fidelity is a corporation.”[16]

But before I duplicated the letters, I made it a point to telephone or email each of the letter-writers and get verbal permission to distribute their letters. Almost all agreed. Then comes the interesting part. I took notes on the conversations, and in the process gathered a lot of information about the MFA trustees. They were indeed an “inside” group, many of whom were members of the super exclusive “Country Club” of Brookline, Massachusetts—a golf and social club where the patrician elite gather, and no outsiders have access to the membership list.[17] One woman told me that she sympathized with those fired curators, but she dared not voice her opinion in her social circle. I had a range of responses including anecdotes about the museum’s underside, its fakes and its scandals.

Patti Hartigan reported on Rogers’s resignation in her August 25, 2015 Boston Globe article, “Malcolm Rogers Has Left the Building—Did He Save the MFA or Ruin It?” Hartigan: “Rogers’s decisions seem controversial because he bucked the old-guard trend, but the modern world of museums has borne him out—the commercialization of art that once seemed so dramatic is now commonplace.” Her conclusion reminds me of Shakespeare’s line from The Tempest (Act 2). “What’s past is prologue.”

One postscript: Today many museum directors have moved to a more collaborative model as they, and we, become aware of the positive inroads that “diversity, equity, inclusion and access” initiatives are making in the field.[18] Strong leadership is, of course, always needed, but that leadership does not have to come from one person. The spirit of inclusion has come back.

[1] I want to thank Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., formerly a curator at the MFA, for his reading of an earlier draft of this chapter and for pointing out some errors of fact. Although I was an insider to the protests, he was an insider to the MFA’s shake-up. I am also grateful to Charles Giuliano for his enthusiasm for my points of view. See also Patti Hartigan, “Malcolm Rogers Has Left the Building,” Boston Globe, August 25, 2015. See https://www.bostonmagazine.com/arts-entertainment/2015/08/25/malcolm-rogers-mfa-boston/ accessed March 8, 2025.

[2] See Hartigan regarding the twenty new hires.

[3] See https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/mass-layoffs/archive/extended_mass_layoffs2000.pdf . Accessed March 9, 2025. There is no space to discuss here the unionization of workers at the MFA.

[4] See Hartigan regarding Rogers’s support of opening the Huntington Avenue entrance—an issue, according to Hartigan, that Rogers raised with the hiring committee and that helped to secure his job offer.

- Charles Giuliano, Museum of Fine Arts Boston: 1870-2020 (North Adams, MA: Berkshire Fine Arts, 2021). The twenty-one people did not seem to include the seasoned curators. See also Hartigan for a brief history of the MFA and its finances.

[6] Fairbanks in conversation with author, summer 1999.

[7] For a sharp precis of the Seminarians vs. Rogers, see Alex Bean, “MFA’s huckster loses Round One to art glitterati,” Boston Globe September 15, 1999, p. D1. Bean’s argument implied that both sides were privileged and out of touch with the working classes.

[8] Author’s conversation with Stebbins, March 6, 2025.

[9] Patricia Hills, ”Boston Massacre,” Art New England, September/October 1999 (Vol. 20, No. 5), p. 5. The term “Boston Massacre” was subsequently picked up by the press.

[10] Temin’s article was published on July 26. Note the British spelling: “judgement.” Can we speculate that Rogers, a Brit, drafted the letter?

[11] Copies of both letters are in Hills Papers, AAA.

[12] See Hilton Kramer, “Now Banned in Boston: A Decent Art Museum,” New York Observer, August 23, 1999, p. 1. Rogers explained his decisions in an interview with Jason Edward Kaufman. See “Staff Sacking Unleashes fury,” The Art Newspaper, (Vol X, No.95), September 1999 pp. 14-15.

[13] Unsigned article, “Museum Reels from Backlash Over Firing Curators,” The Beacon Hill/Back Bay Chronicle, August 31, 1999, pp. 1, 7-8.

[14] Letters and emails quoted here can be found in Patricia Hills Papers, Archives of American Art.

[15] Quoted in Patricia Hills, letter to Members of the Board of Trustees, Museum of Fine Arts, dated August 5, 1999, Hills Papers, AAA. Permission to reproduce was granted by Mr. Hume. Hartigan, op.cit., quotes my comments of 1999 regarding many of the points I make here.

[16] Fairbanks told me that Peter Lynch, the whiz financier who oversaw the Magellan Fund and a close friend of Johnson’s, once said to Fairbanks that “museums should be like corporations.”

[17] A perusal of the internet reveals the extent of The Country Club’s exclusivity, and some sites speculate on new members’ initiation fees—which may go into the seven figures.

[18]In many museums “DEIA” (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Access) is used—to suggest the access that the broad public in offered in the programming of museum exhibitions and events. (See Chapter 25)

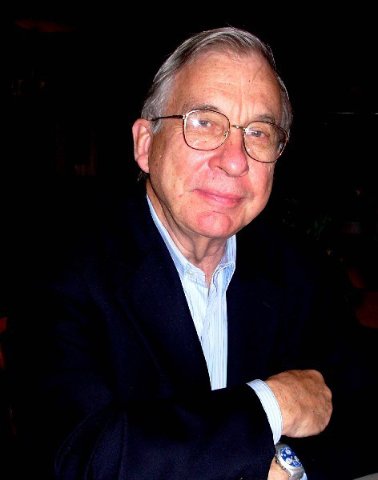

Patricia Hills received her B.A. degree from Stanford University, her M.A. from Hunter College, City University of New York, and PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, 1973. Her first professional position was as a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art (Associate Curator, 1971-1974; Adjunct Curator 1974-87). From 1974-78 she taught at York College and the Graduate Center of City University of New York, and as an adjunct at the graduate schools of Columbia University and the Institute of Fine Art, NYU. She moved to Boston University (1978-2014) where, in addition to teaching, she served as Director of the B. U. Art Gallery (1980-89); Chair of the Department (1995-97; Spring 2009; Spring 2012). From 1983-2013 she also taught courses at the University of Wyoming (1983); at B.U.’s program in Monaco (1991); and at the Freie Universatät in Berlin (2013). She received grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and various residencies at Harvard, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.