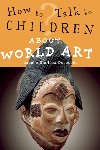

How to Talk to Children About World Art

An Essential Book for Parents and Educators

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 02, 2010

How to Talk to Children About World Art

By Isabella Glorieux-Desouche

Frances Lincoln, 176 pages, 30 color illustration, Trade paper, $19.95

In recent years our interest in and understanding of world art has changed. A significant aspect of this development has been the enormous increase in value. There has been a related increase in the thriving market for fakes and tourist knock offs.

The numerous special exhibitions and museums dedicated to the material have greatly broadened educational outreach. The useful, well organized book by Isabella Glorieux-Descouche provides an instruction manual for parents and teachers.

While not a book intended for scholars and experts in the field it acts as a cheat sheet posing all the right questions, highlighted in bold text, followed by succinct answers.

Before taking children or school groups to the exhibition or museum this book allows for getting up to speed and conducting a meaningful dialogue about exotic and unfamiliar objects. It places world art in an appropriate social, political and historical context.

The approach of the book is frank and precise in addressing difficult and meaningful questions. There is a thoughtful process that tracks how the objects were initially encountered and collected by explorers, merchants and scientists.

During the early phases of world exploration the exotic items were displayed in Cabinets of Curiosities or Wonder Rooms. These predated the development of museums. Initially these objects were not included in the great fine art museums. Instead they were displayed, often rather badly by contemporary standards, in ethnographic museums. The objects and cultures were denigrated as primitive and savage.

An aspect of degrading the culture of "others" fed into European policies to exploit and enslave indigenous peoples through a global network of colonies. Because these newly conquered and exploited peoples were not Christians they were to be exploited or exterminated through the implied genocide of Manifest Destiny or converted to Christ. Usually both.

During the Age of Reason there were debates about how to regard and treat non Europeans. Particularly among less developed tribal and nomadic peoples. There was Rousseau's influential essay about the Noble Savage. That is reflected in literature from the novels of James Fennimore Cooper to Germany's dime novelist Karl May. Tonto, the faithful Indian companion of the Lone Ranger, may be regarded as a Nobel Savage. A Mohawk warrior looks on in intense concentration in the Benjamin West history painting "The Death of General Wolf."

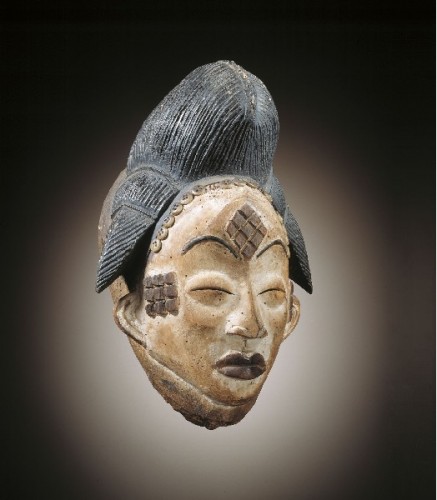

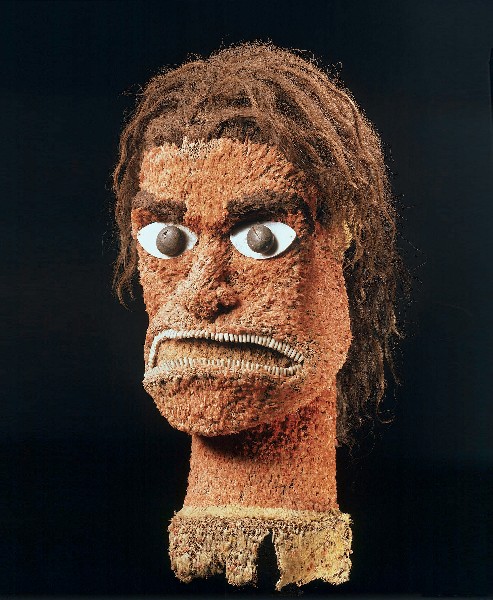

The author discusses how works gathered by museums and private collectors deny their original context and spiritual/ ritual intentions. What was the function and power of the object before it became embalmed on display in a vitrine? How were the materials found and applied? What were the techniques used to create complex and intricate works? Who made these pieces? Why are they not signed as is the norm in Western Art after the Middle Ages? Why do we attach our own notions of beauty to an evaluation and appreciation of the objects produced by non Western civilizations?

One notion of a museum is where to put things that are stolen. The great institutions like the British Museum, the Louvre, the Ashmolean at Oxford, or even Harvard's Peabody Museum provided the physical evidence and specimens of policies of Colonialism. One demonstration of the Imperial might of Great Britain or France is to loot the culture of nations which are dominated and colonized. During the Napoleonic Wars, for example, Lord Elgin, while ambassador to the Sultan of Turkey, liberated the Parthenon marbles. He was saving them from the inevitable hands of Napoleon.

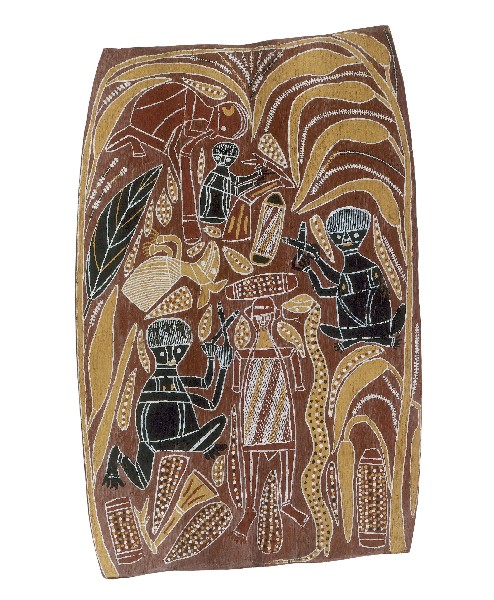

The Greek people have been demanding the return of their priceless national treasures ever since. While this is the most famous example there is an ongoing movement of indigenous peoples to recover sacred objects. Often these are meant only for tribal rituals that are closed to outsiders. Glorieux-Desouche discusses how increasingly Native Americans are attempting to recover traditions, rituals and endangered languages. This is seen in the ever increased visibility and impact of contemporary Native American art.

Modern art has derived great inspiration from tribal artifacts. It was an influence on the development of Cubism in 1907. African arts and culture are seen on Broadway today in such hit shows as The Lion King and Fela Kuti.

On the Mall in Washington, D.C. there is now the National Museum of the American Indian. There is a branch of the Smithsonian Museum in Lower Manhattan. Both museums combine special exhibitions of both traditional and contemporary art and crafts.

This handy volume takes on a rich, complex and daunting task. After providing an overview it includes 30 illustrations with a series of questions and answers on how to approach and understand the objects. The book is essential reading for those seeking to have a meaningful and structured dialogue with children.