Conference on the Black Atlantic at the Clark

Participants Include Artists in Williams College Museum of Art Exhibition

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 02, 2008

Artistic Crossings of the Black Atlantic: The Migratory Aesthetic in Contemporary Art

An Artist Symposium

Saturday, March 1, 2008

Organized by the Clark Art Institute and the Williams College Museum of Art

Related to the Williams exhibition "Unchained Legacies" through June 29

The Artists: Isaac Julien, Fred Wilson, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, Willie Cole and Hank Willis Thomas. Moderators: Lisa Corrin, Peter Erickson, Natasha Becker, Leslie Wigrand, C. Ondine Chavoya, Francesca Royster, Kobena Mercer and Michael Ann Holly.

During the Spring, 2008 semester, the Williams College Museum of Art is offering several exhibitions with related symposia, artist talks, and courses conducted by departments of the college, exploring aspects of African and African American/ Caribbean art.

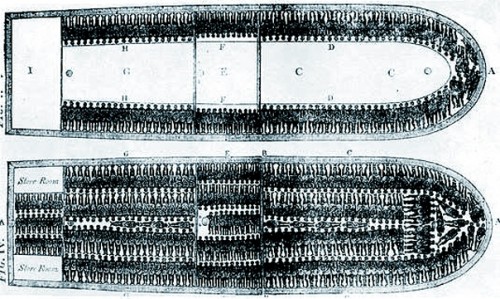

The day long symposium at the Clark Art Institute focused on the visual arts responses to the Middle Passage and the fairly recent terminology of the Black Atlantic. The signifier of this historic phenomenon and a key template for the discussion, as well as specific works in the exhibition "Unchained Legacies," is the ground plan of two decks of a slave ship in the famous 1808 Brookes diagram. The exhibition includes a copy of the book that contained the abolitionist inspired illustration from the library of Thomas Jefferson. The third president of the United States was a slave owner. The author of the Declaration of Independence, through DNA research of his descendents, has been proven to father children by his slave Sally Hemings.

The exhibition at the museum is very small. The works are confined to a single densely installed space that combines works by several artists as well as vintage illustrations and documents of the African Diaspora. It is appropriate to approach this display less as an exhibition than a reference for the college and its broader educational mandates. Talking with some Williams students during the reception that followed the symposium they related how they had participated in classes in the gallery and used the works for class discussion.

The artists and works were selected with a specific connection to the icon of the Brookes slave ship diagram and the history of the Black Atlantic. Accordingly, there was a connection between the artists, their work, and the discussions they presented. This was intended as a meeting of artists rather than scholars. So the discussion proceeded directly from the work. The artists conveyed varying degrees of involvement with the theory and research of the field of black studies.

This approach was inevitable hermetic. Only artists of African descent were included and this applied to most of the moderators and discussants. It inevitably raised the issue of credentials and entitlement when it comes to discussion of race. Willie Cole suggested that a non black artist might have been included to widen the range of the overview. "I know a white artist" he stated evoking a humorous response. While Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (Magda) referenced Ana Mendiata as a "white" artist who, as a fellow Cuban, shared the Afrocentric heritage of the Caribbean. The notion of Creolite was raised by several presenters.

It is always controversial and complex when individuals of one heritage and culture address that of another. Does skin color make one a de facto authority on blackness or whiteness? In an era of globalization, as more and more nations and cultures enter the art world mainstream, just what are the risks and ground rules for curators, critics and culture workers? A recent panel discussion at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, for example, involved artists visiting and responding to what they encountered in China. Does having Italian American genes, in my instance, guarantee greater insights to Italian culture? Surely it is more embedded and encoded in my family history and cultural disposition. But, sadly, while traveling recently in Italy, other than some interesting responses to my surname, I was regarded as an American.

So then who owns culture? Who is the appropriate spokesperson? Should ideas and intellectual pursuit be unfettered by borders and boundaries of skin color and ethnicity? Or have we come so far in this general debate that we are now in the "Post Black" era as suggested by Thelma Golden in an exhibition for the Studio Museum in Harlem? Just what does the discourse of the African Diaspora mean now in the context of Barack Obama as a leading candidate for the president of the United States? With evident emotion Magda indicated respect for Golden but strongly disagreed with the notion of "Post Black." Magda stated that there have always been strong and outstanding women of color. She also described the range of influences of her work from Kant and Rilke to Kurosawa.

Black art or African American art is as dependent on European as on African sources. Similarly, the development of Cubism, as was pointed out, drew on non European influences of tribal art.

Willie Cole mentioned that he had studied with Chuck Close but gave up painting when he discovered that he could never equal or surpass Jean-Michel Basquiat. He talked of how New Jersey and being brought up in an extended female community, seeing the women ironing, had proved to be sources for his work. Later, I told him that hearing him mention Chuck Close reminded me of Pollock studying with Thomas Hart Benton. I asked how Close was an influence in his work? It surprised me when he responded, no to Close, by yes to Benton. "I was an illustrator and Benton was an inspiration to me," he said. He formerly earned a modest living as a street portrait artist and still does portraits of family members and friends which he does not exhibit or sell.

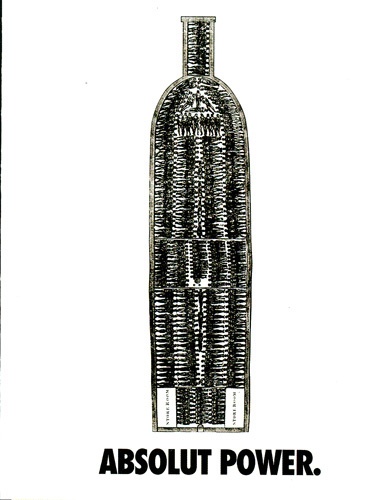

As the youngest artist of the symposium Hank Willis Thomas expressed an awe of sharing the podium with artists whom he grew up admiring. He noted having a (famous) art historian mother. His father, a former Black Panther, later became a Republican. My how things have changed. With humor he described how racial stereotypes can cut both ways. He plays on the notion of black male endowment by adding a "third leg" to an icon of Michael Jordan appropriated from a Nike ad. He reflected that the myth of such endowment is kindah a good thing. Presumably in dating foreplay. But, out on the basketball court, it was too evident that as a black athlete he was an underachiever. His candor was insightful and refreshing. Later I asked him if he viewed himself as a "revolutionary" and if he had concerns that those corporations whose logos he has fun with might come after him? In a work in the exhibition, for example, that slave ship diagram is configured into an "ad" for Absolut.

In another body of work Thomas took the Nike logo and "branded" it to the chests and shaved head of black people. Some of these images, without text, were blown up and actually installed as ersatz advertising billboards. He related how they evoked little or no comment and were just accepted as legitimate ads. In a recent talk at Williams the Guggenheim curator, Nancy Spector, discussed how Felix Gonzalez-Torrez had a similar strategy of making public billboards of his images without text. When they are presented in this context it is normal for the public to accept them as commercial advertising and to remain oblivious to their potential as art.

While there was discussion of the term "Black Atlantic" several artists suggested that it be expanded to "Oceans." Other than Native Americans, all of us are immigrants. A great spectrum of reasons were involved in migration. While Africans suffered the Middle Passage, for many other peoples and cultures, there were few other options. Shouldn't that vast history and heritage be configured into the paradigm of a "Black Atlantic?" Magda raised the issue of other Oceans and migrations, forced and not. What of the slave trade across the Indian Ocean? Or the extensive trade between Northern Italy and the Levant? She pointed out that slaves in Italy, during the Roman Empire, were primarily not blacks by Slavs.

In hearing the artists speak there were differences of how the work resulted from theory, particularly in the paper read by the British, video artist, Isaac Julien, and serendipitously, in the practice of Cole. Fred Wilson described how the work proceeded from circumstance, opportunity and encounter. He showed images of a project in Jamaica where he was invited to make an exhibition noting the anniversary of the end of slavery. He conveyed being surprised to learn that it was only the second such effort on that island. In storage in the museums and historical societies he encountered various materials including botanical specimens, furniture, decorative iron work, prints, books and documents. He planted a garden with flowers, fruits and vegetables which had been imported to the island including many with African origin. In response to a question about reversal and exorcism he stated that he was trying to show the layering of positive and negative aspects of the island and its heritage.

He was asked about the reactions to his project. He described himself as a kind of "Lone Ranger" who just disappears after completing his collaborative projects. Other than attending the opening he did not stay around to encounter critical responses. Although he has Caribbean heritage, this was his first visit. He travels constantly but only to destinations that involve his art practice. In 2003 Wilson represented the United States in the Venice Biennale.

Just what is the very human urge to know who we are and the legacy of our culture and ancestors? What is the impact when we are denied access to that information? What does it mean to be assigned a surname by a slave owner? Or by an official registering immigrants passing through Ellis Island? How many family names and legacies have been lost or reconfigured to become Americanized? Has the notion of the "melting pot" resulted in blurring our differences and edges? Just what does it mean when your Black Panther father becomes a Republican? What did Magda convey when she described growing up with no urge to visit Africa because it was always a part of her family and culture. She discussed how her family retained the Yoruba of her slave great grandfather. As part of her presentation she played a song by Omara Portuondo and translated her ambivalent longing for lost Africa.

Of course speaking and writing about the culture of another race is always risky business. There is too wide a margin of probability of getting it wrong. Cole discussed the "branding" process in his work that is based on finding a flattened iron. This object, heated and applied to paper and canvas, suggests the shape of the diagram of the slave ship. So it evolved as a signifier of the Middle Passage, but not always, as he conveyed with humor. He discussed a large work with brandings formed to make a "sunflower." A critic in Art in America incorrectly assumed that the petals of the flower represented the varying shades of black people. He shrugged suggesting that he was really conveying the notion of heat and energy.

Many of the works of the artists, for me, evoked the notion of reversal and exorcism. By taking a signifier of suffering such as the slave ship diagram, and reconfiguring it as an Absolut ad, for example, the horrific icon is turned into ironic humor and accordingly disempowered. It is similar to laughing at the absurd chorus line singing and dancing "Spring Time for Hitler" in the Producers. How is it possible to laugh at the Holocaust? Or, the Middle Passage? But it also feels necessary. I asked if the work had a common approach of acting against something and involved aspects of reversal?

Isaac Julien showed several multi image videos. He discussed shooting on the shore of Africa and being on location from where ships departed with slaves destined for the New World. There is a sequence in which the incoming waves are reversed. The tide is going the other way across the Black Atlantic. Was this an instance of reversal? Not really was the response it was more about space and movement on the land, at the edge of the ocean, and movement on the ocean itself. This was conveyed in a series of images of fishermen and their boats.

So my synthesis of reversal, exorcism and resistance against something as the point of commonality was not agreed with by the artists. My analysis was too simplistic where the work, in their opinion, was far more layered. The actual Black Atlantic which was being navigated during the symposium is the vast expanse that separates word and image. There is always a large pond to paddle across when we configure the visual into the literal. The symposium underscored that this is work in progress. It was a decision to focus on contemporary art but the actual cultural and historical process bridges a gap of centuries. Hopefully the challenge of the Black Atlantic will expand to include all concerned individuals. There are indeed many oceans and migrations.