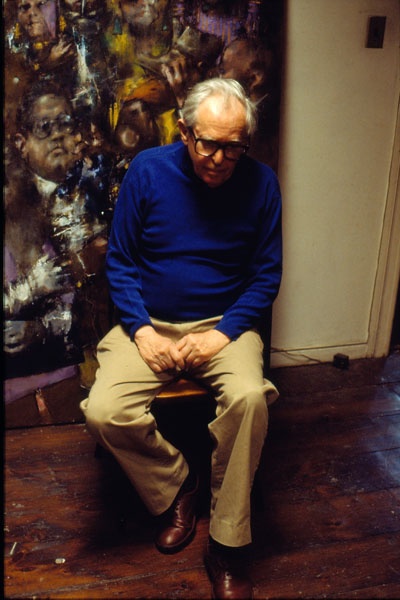

Is Hyman Bloom Still America's Greatest Living Painter?

Katherine French Discusses Danforth Museum Exhibition

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 27, 2007

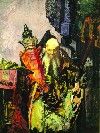

"For at least six months in the 1940s Hyman Bloom was the most important artist in the world," Katherine French, the director of the Danforth Museum of Art, in Framingham, Mass., a suburb of Boston, and curator of "Hyman Bloom A Spiritual Embrace" which is on view through March 11, was discussing the rarely exhibited work of the reclusive, visionary/expressionist artist (born in Latvia in 1913) who lives in Nashua, New Hampshire. "And for two years after that he was the most important painter in America."

That was then and this is now. Does anyone today remember or much care about Bloom, who with his youthful artmate and friend, Jack Levine, and the immigrant, Karl Zerbe, comprised the triumvirate of the Boston Expressionists and their satellites of acolytes making up the Boston School? For a six month long apogee that French refers to a dozen works by Bloom were show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in an exhibition curated by Dorothy Miller in 1942. In the current show, mostly dominated by an inventive series of rabbis from the past decade, there are some vintage works from the 1930s that make a case that Bloom may have been the first Abstract Expressionist as was acknowledged at the time by its greatest exponents Willem deKooning and Jackson Pollock both of whom visited and absorbed the lessons of that exhibition. It was the equivalent of Braque and Picasso visiting the Cezanne retrospective in 1906 prior to the emergence of cubism in 1907.

But what about Arshile Gorky, I asked French, as we dined at a Brazilian restaurant across the street from the museum? Bloom did not travel from Boston and Gorky was unaware of Bloom so they may have been ships crossing in the night. Also, because Bloom remained reclusive and provincial there was a vested interest when Clement Greenberg became the dominating voice of American art criticism in pushing aside Bloom and any other artists who detracted from the spotlight on the artists whom Clem designated for greatness. This is a familiar process in the king making and self promotion that continues to obscure the truth in the study of art history and criticism. The strong prevail or those with the louder voices shout down the meek or reticent. Later Hilton Kramer piled on by stating in a review of Bloom and Levine that he could "smell the pastrami" as he approached the gallery. Years later, at Skowhegan, I confronted Hilton about that cruel and racist remark to which his cool and urbane response was that "It is just a matter of one Jew criticizing another Jew."

As a native Bostonian I grew up on Jack and Hyman and in some ways resisted getting lured out to the Danforth to revisit old work and stale arguments. Over the years I have stated my appreciation of the Boston Expressionists, written about them, interviewed them, chastised curators for bad shows and misinformation (like the hack job some years back at the DeCordova Museum) and didn't much care right now to revisit that scarred battlefield. As I commented to French if all that effort came to no good back in the day, and there is an extensive bibliography of those efforts, why will it make any difference now? In the back gallery of the Danforth is a companion show that includes work by two of my undergraduate professors at Brandeis University, Arthur Polonsky and Mitchell Sipporin. So it's in my blood and why do I need to be reminded of that past? Particularly now when the art world has gone on to other things and could give a damn.

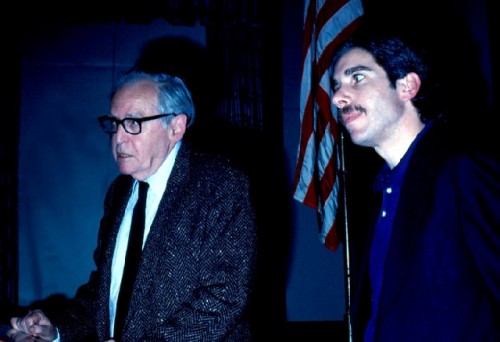

Some years back, I was close to the filmmakers David Sutherland and his then wife Nancy. They separated fairly recently during the drawn out production of the documentary "Country Boys" which aired on PBS following their much awarded PBS series "The Farmer's Wife." It had been great to hang out with Jack particularly as he was known to "hate art critics." I wrote a feature on him for Art New England that I was told he liked. We talked a lot about baseball. Jack was still a Red Sox fan even though he moved to New York after a stint in the military during World War Two. On every level the Sutherland film about Levine was a labor of love but it fell on deaf ears. David wanted to make a film on Bloom but Hyman is notoriously uncooperative with just about anyone from critic, to curator, gallerist or collector. His wife Stella handles sales and diplomacy. I visited Bloom at home but got the typical reception that I could not see work in the studio, was forbidden to tape record or take notes. Hey, why bother? He may be a great artist, butÂ… Dorothy Thompson, however, did care. For years she visited Bloom, followed his rules, got him to talk, went home and wrote it all down by memory. She later curated a show on Bloom for the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton. I attended that opening and it was a rare chance to see Jack and Hyman together.

They were discovered and nurtured when they were kids by Harold Zimmerman who ran an art program at the Jewish Community Center in Boston's South End. He encouraged them to draw from memory and imagination as Bloom does to this day in the Rabbi paintings he admitted to French might be considered Self Portraits like everything he paints. Zimmerman later introduced his prodigies to the Harvard professor Denman Ross who gave them a stipend and tutored them in the classical techniques of painting and composition including Jay Hambridge's Rules of Dynamic Symmetry. Both Bloom and Levine developed flawless Old Master techniques. They were a bit too young for the WPA of the 1930s but both tried to get on the program and were thrown off. It was getting tossed out of the WPA that brought Bloom to the attention of Dorothy Miller as her husband was an official of the board overseeing the artist program.

While Levine more or less stayed with the more conservative political representational style of the 30s and the WPA, Bloom pushed hard against it and this is why he was regarded as a precursor of the Abstract Expressionists. Levine was more aggressive and for a time enjoyed more success and recognition. It helped to move to New York and some of his works like "Feast of Pure Reason" "String Quartet" and "The Gangster's Funeral" have endured as icons of their era. While I like the hilarious later works like "Sinatra in Vegas." Jack is still a terrific and biting social commentator. Hyman, however, turned inward studying the mystical and kabalistic and became an ardent Theosophist. Both renounced their traditional Judaism but their work is redolent of atonement. Why all those Rabbis? Clearly, in today's art world Rabbis are not a hot button topic.

And why a major Bloom show at the small, suburban, Danforth Museum and not the Museum of Fine Arts? That's a huge scandal and illustrates the arrogance and neglect of the "great" museum which has gone out its way to ignore the heritage and legacy of the community it serves. The MFA has mounted several shows that trace the development of art in Boston precisely until the point where the dominating Boston painters evolved from Brahmins to Jewish immigrants. Is it a coincidence that the MFA loses interest in collecting and exhibiting Boston artists after the 1930s? Only to be marginally revived in recent years with the annual Maud Morgan prize in recognition of a single Boston female artist. It is interesting that Morgan was from the famous old Cabot family. Maud was a rebel, bless her, but still a Cabot, who speak only to the Lodges who speak to God. Prior to acquiring the Lane Collection there were few works by Levine, Bloom and Zerbe in the collection of the MFA. Now there are a few. But the greatest works of Bloom and Levine are in the Whitney, Met, Brooklyn and MoMA. Doesn't that say it all?

So how did this important exhibition end up at the Danforth particularly on short notice. Katherine described it as largely a matter of luck. She visited the artist last year with full knowledge of what to expect. But, for whatever reason, the artist was receptive to allowing her into the studio where Stella pulled down painting after painting announcing that they had never been shown. And more amazingly the artist was willing to show them. There had been a retrospective at the National Academy of Design in 2002 and French did not want to repeat that. So the bulk of the current exhibition focuses on recent work rounded out with a nice selection of vintage paintings from the 1930s and 1940s as well as a selection of enormous visionary works on paper. Yes, it is remarkable work. And Hyman may be America's greatest living painter. But nobody really gives a damn. Except for a few of us old coots.