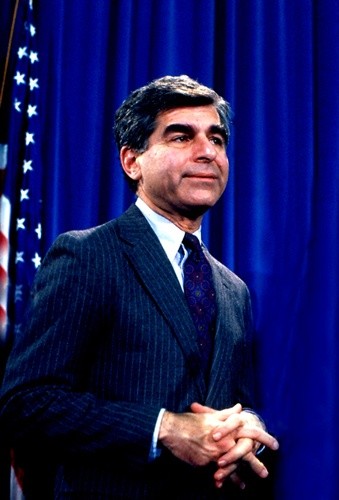

Joe Thompson Director of Mass MoCA

Reflecting on 25 Years

By: Joe Thompson and Charles Giuliano - Feb 22, 2012

Charles Giuliano In the e mail setting up this meeting I asked you to consider the quote “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” (Sir Winston Churchill, Speech in November 1942.) To set the tone for an overview of the 25 years that you have been director of Mass MoCA. As a critic and reporter I have been following the story from the beginning.

Having been here all that time perhaps I might begin by asking if you are ever going to get a real job?

Joe Thompson It’s a tough world out there Charles.

CG It’s amazing.

JT Sort of old fashioned.

CG It was a real struggle. You had some tough years in the beginning. What was it ten years?

JT Twelve. Last year was a milestone. We were finally open longer than it had been to get open to begin with.

CG That was a tipping point.

JT Yes. It was twelve years in the making. We’ve been at it now coming up on thirteen years. Which feels good. I find your quote interesting because it’s hard to find beginnings and ends in this business. I once commented that I like to fly (he owns a small plane) because you know when the flight starts and when it is over. It has a definitive quality to it. Which a project like this simply doesn’t have.

I think your instinct though is correct. We have reached certain milestones. One thing that a lot of people don’t realize is that we opened in 1999 with a little over 200,000 square feet of this complex developed. The total footprint of developable space is about 600,000 square feet on 17 acres. I guess if we count the R&D of the space we acquired across the street, which is now a Court House, it is closer to 650,000 square feet. When we inherited the buildings there was about 780,000 square feet. We took down a couple of buildings which were falling apart. Leaving all told, I’ll count across the street, about 650,000 square feet.

CG Overall the buildings were in pretty good shape.

JT In pretty good shape. I would say in marvelous shape, pristine in 1987-88 when we first proposed Mass MoCA. By the time we started construction in 1996-97 many of the buildings had deteriorated badly. The roofs leaked. There was grass growing in the floors. The pigeon and raccoon population was high. There was a lot of wild life in the buildings. If you take that 600,000 square feet we opened with a little over 200,000 square feet. As of today I think we’re right around 450,000 square feet developed.

CG Does that include the museum as well as commercial space?

JT Yes. Which means that in twelve years we have doubled what we opened with.

CG Can we break it down?

JT It’s a quick deduct. You deduct about 125,000 square feet from 450,000 square feet.

CG Commerical.

JT Yeah. So that leaves about 325,000 square feet as non commercial or museum space; performing space, back of house, storage, hvac in the basement. My point is that since opening in 1999 the developed foot print has doubled. From 2000 to 2006 we added commercial space. Building One was the first we did. Then Building Two where Storey Publishing is located. (The company employs 50.) Then Building 13 where Donovan & O’Connor (a legal firm) and our other tenants are. On the Marshall street lot which is a major addition. Then we picked up the Court and Social Security building across the street which we bought. We purchased that from Sprague Technologies. That was not a part of the original deal. We borrowed money and renovated it as the Court House and the same thing with the Social Security offices. As commercial real estate development.

CG You currently earn $1.5 million in income from tenants.

JT That’s about right.

CG Which goes toward a $7 million annual budget.

JT More like $6.5 million.

CG You make $280,000 through an annual fund raiser in New York.

JT Better than that last year.

CG Your salary is about $275,000 which is about 5% of the annual budget.

JT I wish it were.

CG The base salary is $160,000 but you got a $100,000 bonus. (2009-2010)

JT $50,000. Your numbers are right with one exception. My base salary is $160,000 and I get a retention bonus.

CG What’s that? If you agree to stay?

JT That’s right.

CG Perhaps we are jumping ahead a bit. But if you look at other comparable institutions, the ICA for example, they were founded in the 1930s and are only now endowing the positions of director and chief curator. It has taken more than 75 years to establish financial stability. Compared to which MoCA is very young having been operational for only a dozen years. It seems that at some point MoCA would logically endow the positions of director and chief curator.

JT It’s a good idea. Endowment always comes hard and late.

CG That sounds like a mantra that should be cast in bronze. It seems like a class at Harvard Business School.

JT It’s a function of the reality that donors that give endowment are both undergirding the institution as well as betting heavily on its future existence. You don’t get that kind of money early in life unless you have a single benefactor. Like when an individual brings a chunk of cash as well as a chunk of art to found an institution. There are many institutions which have been founded on that model. Often when institutions are a bit more scrappy, like Mass MoCA, endowment money comes later in the cycle when people are fairly confident of the future. It’s a hard chicken and egg problem to get past.

CG Looking at the 2009-2010 tax returns I don’t really see an endowment in the figures. Perhaps I am not reading them properly.

JT Really? Because it was just beginning to accrue in those years. We began our ($37 million) campaign in mid 2007. Many people make pledges which are paid in over four, five, or six years. They’re pledges and they’re made good when they’re paid.

(Previously we reported that "In announcing its $37 million capital campaign the museum reported that it has secured some $25 million of that overall goal including most if not all of the $8.6 million for the Lewitt building. As a part of its "Permanence Campaign" $16 million will be designated toward an endowment. For programming support it is earmarking $6.4 million and another $6 million toward debt reduction and a reserve fund for maintenance. Of the $12 million yet to be raised the museum plans a $4-5 million regional and $7 million national campaigns.")

CG What was the goal of the campaign?

JT It was a complicated campaign because it had several parts. The Sol LeWitt project was a part of the campaign which was to renovate the building.

CG I thought that Yale paid for that.

JT Oh no.

CG So it was a partnership?

JT Absolutely.

CG I was under the impression that you got the art, a free building, staff and maintenance for life.

JT Haven’t you heard the expression “There’s no free lunch?”

CG It seemed from the outside that Yale had the LeWitt estate, which included plans and designs, but no walls on which to execute them. In taking the estate they had responsibilities to the artist. MoCA had the walls. In that sense perhaps MoCA held the aces in the deal.

JT It was a deeper partnership than you just described. At first Yale and Mass MoCA, largely Jock Reynolds and Myself, engaged, with our boards, in raising the money together. We split it with Mass MoCA taking on the responsibility of raising money for the bricks and mortar. We had to fix the building. Fix the roof. Renovate it. Bring hvac to it. Yale took on the primary responsibility to raise the money to feed and house the artists. There were sixty some artists here for seven months. That was a significant undertaking. We were joined later in the collaboration by Williams College which also helped with fund raising. The three of us together went to raise an endowment the income of which would go to pay the incremental cost of heat, light, power.

CG I estimate that it cost some $500,000.

JT You’re low.

CG By half?

JT By order of magnitude. (Closer to $8.5 million)

CG How can we describe the impact? How did it change the institution both aesthetically as well as its mission and mandate?

JT It did several things some of which were anticipated and some which weren’t.

CG Was it a game changer?

JT Oh yeah. Transformative. For several reasons some of which were unpredicted. One; we were quite confident that the art was going to be great. We knew that he was a great artist and that if you saw him in that depth and scope it would be a really rare and marvelous experience. I was confident that having a great monument like that in our three ring circus of changing exhibitions would have great beneficial effect. Just for the viewer experience of people coming here.

You live here all year long. When people come in the summer and fall the cupboards are always full. We carefully keep the galleries chockablock with exhibitions. But if you came to the museum in the winter or spring you might find 25,000 to 30,000 square feet of space closed. The equivalent of a whole Whitney Museum. If we were in the midst of one of our big changes. Before LeWitt for visitors who came from afar a third of the museum could be down.

CG What’s fascinating with the long term, somewhat permanent LeWitt installation is that it brings us back to the original concept of Tom Krens that Mass MoCA would be a warehouse for low maintenance minimal art from the Panza and other collections.

JT That original idea of being a depot for mostly minimalist and American art got realized and it’s called Dia Beacon.

CG And Chinati Foundation (Marfa, Texas as well as the Donald Judd Foundation).

JT That’s even more focused. It’s a beautiful, valuable, great idea. It has little to do with what Mass MoCA ended up being.

CG How did that change of mandate come about. Did it occur when (Tom) Krens left for the Guggenheim? Was it through your initiation? What was the thinking process and how did it evolve?

JT It happened in several ways. That first idea was something I fought for tooth and nail. For three almost four years. Then secondly realized for a whole complicated set or reasons that it was simply never going to happen here. As beautiful an idea as Tom, Michael (Govan) and I thought it might have been.

CG The concept was to warehouse work that would be low maintenance.

JT Put em up, dust them off, change the light bulbs. The idea was matching up works that required a lot of space and these large, well lit galleries we have here. When I started raising money for the project, the State, which had always been a partner, had money problems. In the late ‘80s and ‘90s it started asking for greater and greater amounts of non State support. Cash.

Which sent me out on the road. Talking about this idea in New York, Chicago, Low Angeles and Boston, to say nothing of North Adams, Williamstown and Stockbridge, Lenox and Lee. I was faced with a question which was repeated over and over again. This is from people who cared deeply about contemporary art. I was talking with the great collectors of the country. With my tin cup in hand trying to raise money for this. The question was “Are you sure people are going to come twice?” As beautiful as we all knew it would be would people be moved to come back and make repeat visitations? If there’s no change. So that was one particularly hard, pointed question particularly from people who most loved this work. I took it seriously.

CG How do Dia and Chinati deal with that? (Fixed galleries with permanent collections.)

JT They are both endowed institutions. They are not reliant on visitation. It’s a different model. If you have money and your focus is on a very small band width of the whole world you are interested in destination, died in the wool Donald Judd fans. Or Carl Andre fans. Your criteria are different. They are both able to finance that relatively rarified point of view.

So one impulse for the change was this very good question.

Second was our early collaboration with Jacob’s Pillow. During the time when Sam Miller was the director there. Sam and I became friends. He pointed out that the performing arts world had the same set of needs for space and time. The need for a place to make new work. He said “If you’re really serious about making a museum of contemporary art you should really consider expanding to include the performing arts."

That also dovetailed with another set of comments I was hearing around Berkshire County. Remember, this was before the Clark Art Institute was operating as it does today. (Under director Michael Conforti.) With an ambitious program of changing exhibitions which bring repeat visitors every summer. It was a much quieter institution. It had 90,000 to 100,000 visitors a year.

CG That’s where you trained?

JT No. I went to Williams College and graduate school somewhere else. As a Williams undergraduate I went to look at art there all the time. The Clark was really important but I wasn’t a graduate student at the Clark.

(Beginning in 1982, Thompson served for three years as preparator and exhibitions designer at the Williams College Museum of Art, and in 1984 was awarded a residency at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC as the James Webb Fellow for excellence in the management of cultural institutions. From 1988 - 90, he held the post of lecturer in contemporary art at Williams College and the University of Pennsylvania. A 1981 graduate of Williams College, Thompson received an MA in art history in 1986 from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was named an Annenberg Fellow. He earned an MBA from the Wharton School of Business in 1987, along with the Morganthau Fellowship in recognition of his work in public policy and management.)

My point is that the Clark was not what it is today. And the Williams College Museum of Art was just finding its feet as a museum. Under Tom’s leadership in the early ‘80s.

CG Was that when they built the Charles Moore designed addition?

JT It’s about the same time. The college museum was just being born as we think of it today. Norman Rockwell Museum was running out of his former studio. It hadn’t built its new building yet. (Designed by Robert A. M. Stern opening in 1993.) Again, then it had 100,000 visitors a year not like the 200,000 visitors it has today.

In short when people thought of Berkshire County it was first and foremost Tanglewood then Jacob’s Pillow, Berkshire Theatre Festival, Williamstown Theatre Festival. The identification of the Berkshires certainly wasn’t with its museums.

Many people pointed out that if you aligned and wanted to have a Berkshire brand, you needed to have not just a symbolic performing arts program but rather a significant performing arts component and one that could deal with was Laurie Anderson, for example, a visual artist or a performing artist? Bob Wilson. What’s his practice? There’s a whole range of artists who are very hard to pin down.

All of that led us to believe that if you wanted to become a great platform for contemporary art you had to become a great platform for the performing arts. As a substantive part of the overall programming.

You asked how did we get from a static box to a focus on changing exhibitions and performing artists which is what Mass MoCA is today. That’s how. Through listening and hearing criticism. Thinking deeply about visitation patterns. And the relationship between performing and visual arts. It led me to doing a couple of things. We went from a small auditorium space to the Hunter Center and the other stages which we have. We moved toward a exhibition model which was almost entirely focused on changing exhibitions. Not permanent collection.

Having said that long term installations like LeWitt, I think, are incredibly important. Making the museum into a place. They visit the galleries multiple times. Visitors begin to associate powerful works of art with a particular place.

For me Brancusi and Philadelphia read the same. Albright Knox in Bufffalo and abstract expressionism.

CG For me it’s Duchamp and Philadelphia.

JT I’m with you on that. There are a few places when you mention them they bring up works of art.

CG Now Denver and Clyfford Still. North Adams and Sol LeWitt. (By 2013 Anselm Kiefer)

JT Exactly.