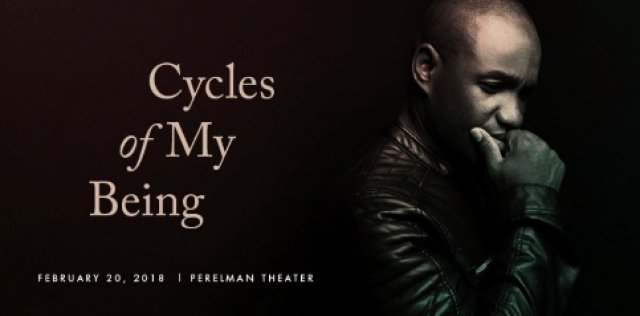

Lawrence Brownlee at Opera Philadelphia

World Premiere of Cycles of My Being

By: Susan Hall - Feb 21, 2018

Cycles of My Being

Music by Tyshawn Sorey

Lyrics by Terrance Hayes

Lawrence Brownlee, Tenor

Perelman Theater

Kimmel Center

Opera Philadelphia

Philadelphia, Penn.

February 20, 2018

Photos by Dominic M. Mercier for Opera Philadelphia.

Listening to tenor Lawrence Brownlee sing the classic bel canto repertoire for which he is justly well-known, you sometimes sense that the artist is hidden. Turns out that Brownlee has been chomping at the bit to tell us about himself as an American black man.

Searching for a way to bring his portrait to the concert stage, Brownlee engaged two MacArthur fellows. Tyshawn Sorey is familiar as a International Contemporary Ensemble member. He has drawn a rich and varied portrait of Josephine Baker for Julia Bullock. He is a fabulous drummer.

Now, joining poet and lyricist Terrance Hayes, he has composed a musical portrait taking us inside a black American male. Eldridge Cleaver wrote a truth many years ago. The American black does not know what it means to be a man without white supremacist standards based on domination and violence.

Brownlee was not interested in ranting. He wanted us to hear in music and words what it feels like to be him. His goal is “mutual respect, understanding and communication across races and generations.”

The evening began by introducing us to each of the American black male musicians who would come together in the instrumental ensemble of Cycles of My Being.

Randall Mitsuo Goosby is a twenty-one year old student of the violin at the Juilliard school. He etched beautiful melodies in the first movement of Brahms’ Violin Sonata. He has explained that Brahms stepped on melodies all over the countryside as he composed this piece. We could hear them in the Perelman Theater air. Later Hayes words floated: “Do you love the air in me as I love the air in you?”

When he was a young student at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, Samuel Barber composed a cello sonata which Khari Joyner played. He digs deep into Barber. Again, we would listen to plaintive melodies which moved us closer to our listening ears.

Alexander Laing played traditional spirituals on the clarinet. He had wanted to have his instrument join the chorus in this classic black form.

At the piano, raised to half mast for the early program, Kevin J. Miller picked up the beat for each of these pieces.

Before the world premier began, the piano lid was raised to full upright position. All of the instrumentalists returned, accompanied by the composer/conductor. Lawrence Brownlee began to sing Inhale, Exhale. The first word is “America.”

The music began almost in a whisper. We wonder if there is a song to be heard here. The violin often bows two notes, a very quiet hello. It takes bravery to sing about hate and hope. Hissing and staring are expressed, but with fear behind them. Yet the question is asked, “America, do you care for me as I care for you?”

Sometimes the piano plays successive funereal chords. The clarinet can sound like a shofar calling out in the desert, or the parting of the Red Sea.

Sorey conducts with a small baton in his right hand. He is showing rhythms and a pace.

We are fixated on the singer. Brownlee takes the lines which often express awkward dissonant leaps as he shows us his pain without directly referring to it. Some words are held very long so that we can wrap ourselves into them.

Only one phrase is spoken, not sung: “You don’t know me. Still you hate me.” It stands out.

Terrance Hayes did not know the word ‘hate,’ when Brownlee mentioned it as a theme. “Hate,” he laughs. “Why, I never use the word.” Brownlee himself wrote the songs Hate and Hope Part 2.

In the final song, all the instrumentalists join together as a supporting chorus. “I know,” they sing. Over and over.

The power of this song cycle is difficult to express. Members of my family taught runaway slaves and freed men long before the Civil War began. They founded Lincoln University, from which Thurgood Marshall and Langston Hughes graduated. I teach black American boys in the justice system. I have spent years trying to understand professional black baseball players and black players in the criminal underworld. Until Cycles of My Being, I always had to admit in the end that I did not/could not understand.

In this song cycle, created to “show the day-to-day life of a black man in America and thoughts and questions he experiences as he moves through the world,” I at last had a glimpse of what it means for these men. I only wish that Hughes and Marshall, Paul Robeson, Michael Jackson and Willie Stargell were alive to hear their song. Lawrence Brownlee, his fellow artists and Opera Philadelphia have taken a giant step forward to helping us solve what is universally-acknowledged as America's most intractable problem. They have at last helped us understand through the universal language of music.