Mind Over Matter: Photography as Verification

Material Witnesses: Photographs of Things at the Clark Art Institute

By: Janes Hudson - Feb 20, 2010

Material Witnesses: Photographs of Things

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

January 15, 2010 - April 11, 2010

225 South Street

Williamstown, MA 01267

413.458.2303

As a photographer I am curious about the history of the medium, and the way it characterizes so much of what we believe to be the 'real' world. Our collective memory is recorded in the vast photographic production of the medium since its invention in 1839. From the fond Instamatic or Brownie image to the ubiquitous cell phone shot, the post-war generation has documented both its personal experiences as well as those of the world at large. Since the days of U.S. government-sponsored forays into the west to promote settlement, the photo has framed history and desire, fantasy and evidence, danger and triumph.

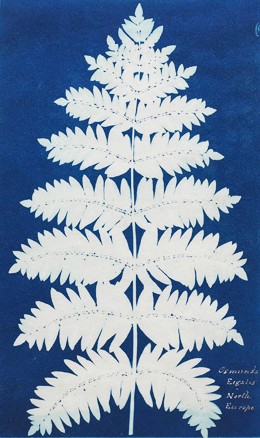

In the early days of the emerging medium, the photograph was considered a scientific tool, an objective eye for archival certainty. There were a number of chemical solutions to the process of acquiring and printing the image on paper: the salt print from wax paper, the cyanotype or blue print, the albumen print and others. What we see of these old images are browned down and faded as the chemicals degenerate and oxidize. It is this 'look' that concerns me.

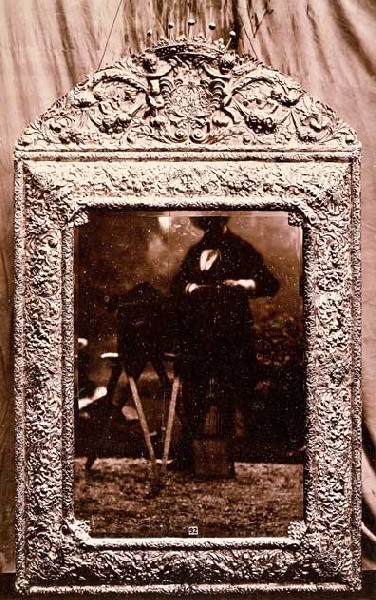

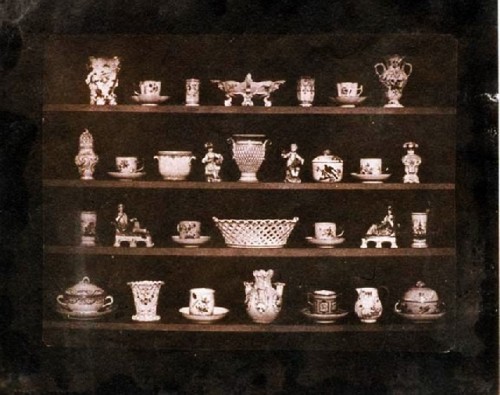

Material Witnesses: Photographs of Things is currently on view in a small, and somewhat hidden gallery at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA. Tucked between Dutch Masters and Renaissance painting, and comprising no more than 20 images, this exhibition of works from the Troob Family Foundation and the Clark, explores a range of processes as well as the purposeful inventorying of objects. We receive a kind of catalog of 'evidence' to secure the provenance of the objects and places represented. Given that the photographic camera was a product of industrialization, the emphasis in these images is to use that mechanism to establish the veracity of the antiquities within a collection. It acts as a kind of insurance policy against damage, theft, or forgery.

Given the Victorian's faith in science and technology, this mechanism purports to a truth so objective in its observation that it obviates human bias. But once done, the act of viewing the photograph instead of the 'original' becomes more and more the habit of the viewer. As Walter Benjamin noted in his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction "that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art,"* In these images we see an early instance of a distancing from the subject. However, because the photograph is a print, duplicates may be produced and distributed widely. So we lose acquaintance with the original and its provenance, but experience the availability of the images.

Technology breaks the space of the body. When we walk into the gallery and witness the historical artifact, there is recognition within the gaze of an intimacy made of belief. In this instance of the technological dimension, here removed once through the first photograph, and then again by reproducing it digitally (then processing the image through Photoshop and email, and finally uploading it to this site) that belief system is challenged.

So what about the 'look?' It represents a kind of innocence, a reference to a time where the mechanism of technological media had not yet swallowed the world whole. It allows us to consider a subject matter that harkens to that time when most lives were lived in the flesh. Of course we need that image in order to remember, for the reality of that kind of life is being foreclosed.

We have come, in 'Material Witnesses', to the threshold of the tech wave. We are in awe (a factor in the recognition of the 'aura') of the primitive prints, the historical reach, and want to resurrect that withered aura in these documents. We know who owns them, and where they are kept, and we know that they've been collected not for what is represented, but for their historic and aesthetic value as photographs.

Perhaps the value that we endow to things comes not from something intrinsic but from the personal and collective care we give them.

* Benjamin, Walter, ILLUMINATIONS, Essays and Reflections, pps. 217-251, 1968, Schocken Books, New York