I Due Foscari by Verdi

Produced by West Bay Opera

By: Victor Cordell - Feb 18, 2019

In an era of fake news, alternate facts, and trial verdicts reversed because of erroneous testimony, we are well attuned to the corrupting effects of falsehoods. In this adaptation of The Two Foscari, Lord Byron’s play set in the 15th century, Francesco Foscari is the Doge, the most powerful man in democratic Venice. But when his son Jacopo is accused of murder and treason, he finds that his power has limits.

In an adventurous programming decision, West Bay Opera has mounted a highly rewarding production of this seldom-performed Giuseppe Verdi opera about the quest for justice against false testimony. The appeal of the opera and this realization of it beg the question why this is only the third ever fully staged American production.

Debuted in 1844, I Due Foscari was Verdi’s sixth opera. His librettist was Venetian, Francesco Maria Piave, with whom he would collaborate on ten operas, including two of his most famous, La Traviata and Rigoletto. Piave was also the librettist on Ernani, which made Verdi the new toast of the opera world and which immediately preceded I Due Foscari.

The landscape for Verdi’s musical dramas is the world of the noble, the rich, the influential. And while many of his pageants are painted on a large canvas, others are miniatures that largely focus on the private conflicts of individuals. I Due Foscari is one of latter, even though several lavish chorus scenes appear to enrich the overall composition.

Although the storyline is straight forward and noteworthy, the libretto is somewhat wanting. Jacopo is trying to clear his name for crimes he says he did not commit, and his wife Lucrezia fiercely advances his cause. However, the reasons and specifics of the crimes are unclear. Francesco’s ambivalence about supporting his son is murky as well, but at least that uncertainty creates dramatic tension.

Like much early Verdi, I Due Foscari lacks the memorable arias and ensembles that appear on compilation recordings. However, it may be that we just haven’t heard these enough to become familiar with them. But, fear not. Verdi’s thematic strength and melodic sense are very much in evidence, yielding a score that compels from beginning to end. Paradoxically, though most encounters in the opera are intimate, with two or three principals, the singing is robust and the action animated because of the nature of the confrontations. The composer also experiments by breaking some stultifying conventions of operatic form and employing his first rudimentary use of leitmotifs, with each of the lead characters linked to an instrumental section or a riff.

Tenor Nathan Granner is Jacobo, and from his Act 1 cavatina, he stamps his vocal power on the role. He is in a constant state of anguish, and his music calls for coloratura runs and leaps at high volume that he manages with great skill. In Christina Major’s interpretation of Lucrezia, it is hard to imagine a Verdi heroine with greater challenge and vocal fire. Although the dramatic coloratura soprano has performed lyric roles, she attacks this one with exhilarating force and dominates the stage when she sings. Often in a rage, her penetrating voice pierces the air, yet she exhibits great dynamic control and manages the quieter prayer and duets with both male leads with great success.

The Doge, Francesco Foscari, is sung by baritone Jason Duika, and regrettably, he suffered an allergy attack just before opening night. But courageously, and given the absence of an understudy, he soldiered on in a strained sotto voce. While his vocal ability was limited and stressed, his presence as the weakened ruler made a difference. His commitment to ensure that the audience received the experience they came for was appreciated by all, and he deservedly received a standing ovation.

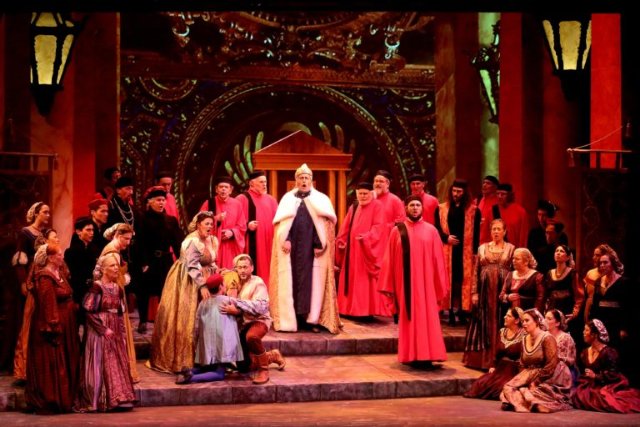

Musical integration by conductor José Luis Moscovich creates a full and balanced sound. A minor defect is that the precision of the men’s chorus did seem to falter occasionally. The look of Peter Crompton’s staging works nicely and is sometimes lush, framed by columns, with a back wall used for Frédéric O. Boulay’s attractive projections conveying the feel of period interiors and cityscapes of Venice. However, steeply-pitched, across-stage step-ups impede mobility around the stage; limit group clustering; and restrict action points so that, for example, the Act 3 ballet is restricted to the apron. Also, the intrusive rear columns steal space without seeming benefit. The stage is best dressed when the chorus is present in the beautiful, rich, and multitudinous costumes by Callie Floor.

I Due Foscari with music by Giuseppe Verdi and libretto by Francesco Maria Piave is produced by West Bay Opera, and plays at Lucie Stern Theatre,1305 Middlefield Road, Palo Alto, CA through February 24, 2019.

Courtesy of For All Events.