Amanda Forsythe Keeps The Garland Fresh

Boston Baroque Presents Rameau's Rarity.

By: David Bonetti - Feb 18, 2014

“La Guirlande, ou Les fleurs enchantée”

(The Garland, or The Enchanted Flowers)

Music by Jean-Philippe Rameau

Libretto by Jean-François Marmontel

Boston Baroque

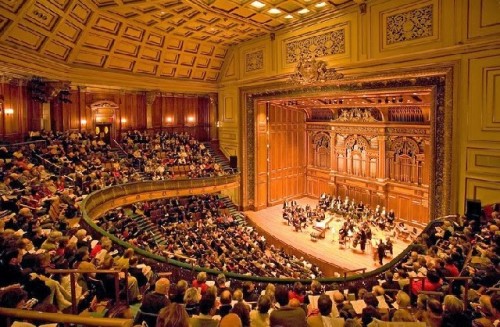

Jordan Hall, New England Conservatory

February 14 & 16

Conducted by Martin Pearlman, Boston Baroque Music Director

Cast: Myrtil: Lawrence Wiliford; Zélide: Amanda Forsythe, Hylas: Andrew Garland

A chorus of shepherds and shepherdesses

Also on the program: Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s “Te Deum” (H.146) and Rameau’s Suite for Orchestra

Bostonians don’t often get to hear the big stars of international opera perform here live. To hear Jonas Kaufmann in Massenet’s “Werther,” they will have to Amtrak down to New York City. Some will satisfy their desire to see the hottest tenor in the world by going to a movie theater and watching a live transmission of a performance, but they are only deluding themselves - they are seeing and hearing only a facsimile of the real thing.

But Boston does get to hear Amanda Forsythe, and that’s fair compensation. Forsythe specializes in early opera: Handel, Monteverdi and Purcell, and her repertoire extends in time to Mozart and Rossini. In those operas, Forsythe has few equals in the United States. Listening to her sing the silly role of Zélide in Jean-Philippe Rameau’s one-act opera “La Guirlande” Sunday afternoon was like getting admitted to heaven while one is still alive. The program was promoted as a Valentine weekend celebration, and when Forsythe’s voice soared with ornamentations during her extended Scene III series of monologues, it seemed that the entire audience fell in love with her.

When the short work was over – with some cuts of non-vocal dance music, it lasted only about 45 minutes - I kicked myself for not having gone to hear Forsythe Friday night as well. How could I have failed to foresee that I would want to hear her in the role, a true rarity, more than once?

It is Forsythe’s great fortune that she gets to perform with other singers who understand Baroque style as well as she does, in this case haute-contre (high-tenor) Lawrence Wiliford and baritone Andrew Garland. And that she is backed up by orchestras – here the superior band Martin Pearlman has assembled for his Boston Baroque, celebrating its 40th anniversary this season – that are equally fluent in the music of the 17th and 18th centuries. Boston isn’t known as the US capital of early music performance for nothing: it is individuals like Pearlman and groups like Boston Baroque that give it that distinction. With, in addition to Boston Baroque, the Handel & Haydn Society, next year celebrating its bicentennial, the Boston Early Music Festival presentations and smaller groups like the Cantata Singers, the Boston Camerata, Emmanuel Music and Blue Heron, you can hear international-caliber period-instrument performances of music from the Middle Ages to the Romantic era nearly every week here during the season.

Pearlman assembled an intelligent program featuring the two great outsiders of the great age of ancien régime French music. (Neither Rameau (1683-1764) or Charpentier (1643-1704) received support from the royal court.) It started with the best known of Charpentier’s six Te Deums – its familiar kettledrum-and-trumpet opening is the theme music for Eurovision. It moved on to an orchestral suite by Rameau assembled from overtures and dances of four of his operas that suggested the stylistic variety he was able to bring to different dramas. And after intermission, the payoff - “La Guirlande,” a one-act pastoral comedy for three characters and chorus.

The story is as frivolous as only French opera can be. There are a shepherd, named Myrtil, and a shepherdess, called Zélide, who are in love. They have exchanged a pair of garlands that will stay fresh as long as they are faithful to each other. But Myrtil has lust in his heart and his garland fades. He places his wilted garland on Cupid’s altar, asking him to refresh it. In the meantime, Zélide fends off the advances of the shepherd Hylas. When she sees Myrtil’s wilted garland on Cupid’s altar, she realizes that he has been unfaithful, but she replaces his dead flowers with her still fresh wreath. When Myrtil returns, he finds his garland refreshed, assuming that Cupid has answered his prayers, but when he sees Zélide’s, he thinks she has been unfaithful. Not to worry – this is only a one-acter after all. Cupid intervenes, bringing the dead garland back to life, and everyone lives happily ever after – at least until the next temptation – and the opera ends with all the shepherds and shepherdesses celebrating the god of love.

Boston Baroque presented “La Guirlande” as a concert piece, not even semi-staging it as it has done with opera in the past. (It will semi-stage Monteverdi’s “Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria” in April.) There were no dancers, which seriously compromised the work. But with Amanda Forsythe performing, there was no way the pastoral would not be enacted. And her pair of shepherds proved game as well. The men wore tuxes and Forsythe wore a long, white, shepherdess-appropriate gown with her colorful garland in her hair. They interacted and brought a modicum of drama to the performance.

On the flimsy scaffold of an off-the-rack pastoral, Rameau hung some great music. From the orchestra’s opening chords, one heard the highly distinctive sound world of a composer who made music that sounds like none that came before or after. The brief overture, or ritournelle in French, was sweet but sad, suggesting that Rameau knew the ways of the world all too well, slightly acidic tones tempering the overall sweetness of the sound. Pearlman led the orchestra with verve. It was impressive to hear how idiomatic he was in this light but spirited music - and how different it is from the Italo-Anglo-German music of Rameau’s great contemporary George Frideric Handel, whose “Messiah” Pearlman conducted with equal sympathy in December.

Myrtil enters, lamenting his fickleness. Singing with understated drama, Wiliford, who sings mostly in Canada, paid extraordinary attention to the text, making each word, each vowel, clear. Possessing a more masculine sound than the typical counter-tenor, he was able to muster clarion vocal strength when necessary, as in his lament, “Votre éclat s’est terni quand j’ai manqué de foi” (Your bloom faded when I betrayed my troth), and in the repeated cries of “Brillez” (dazzle) at the end of his entry aria.

Andrew Garland, who has impressed in roles such as Tamino in the Boston Lyric Opera’s “Magic Flute,” was fine in the too short role of Hylas, the shepherd who puts the make on Zélide.

But the afternoon belonged to Forsythe. As fine an actress as she is a singer, she imbues everything she sings with the force of life. Where other singers make you aware of the effort expended to hit high notes (or low), Forsythe makes it all sound easy. She moves without break through the vocal registers that loom as roadblocks to other singers. And her voice is rich and full, ranging from silvery to creamy. She occupies the stage with a natural sexiness, passing the joy she feels in singing on to her listeners. (In terms of that ability to connect with an audience, Natalie Dessay and Cecilia Bartoli today seem to have it, as did the late Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, who also emerged from Boston’s early music scene, and Shirley Verrett - not to mention, of course, Maria Callas. Among male singers, there are not so many – Kaufmann seems to be one of the few on the stage today with a physical immediacy that matches his vocal allure.)

Anyway, when Forsythe walked on stage, looking like a slightly shamed shepherdess contemplating her flirtation with a man not her beloved, the afternoon took off. After dispatching her would-be lover, the hapless Hylas, she embarks on a lengthy monologue that explores her love for Myrtil, constant even with the evidence of his unfaithfulness on Cupid’s altar.

This being a pastoral, of course, there are evocations of nature. “Tout languid dans nos bois quand l’hiver les ravages” (Everything in our woods languishes in winter’s blight) resonated with the audience perhaps more than it would have if the program had been performed in spring rather than the most discontented winter in many listeners’ memory. Through the long sequence, Forsythe filled the air with sounds that rivaled nature’s, paired with orchestral color that combined to paint a picture of a natural world alive with flora and fauna and the awakening breezes of spring. Forsythe accompanied that previously quoted line with trills that undercut the severity of winter’s blight, and in the next phrase, which cites “Zephyr beginning to sigh,” the orchestra sighs with it. Later when the “le rossignol s’éveille,” (the nightingale awakes) Forsythe sings a duet with a flute, mimicking the sounds of a bird. And there is a wonderful trill-filled duet with violin.

Later, when Myrtil and Zélide are reunited and reconciled, they trill together deliriously and walk to the back of the stage hand in hand, each wearing their own ever-fresh garland as the chorus of shepherds and shepherdesses prepare to sing, “Aimons, aimons, qu’en nos bois tout soupier, Que tout inspire les désirs, Que tout respire les plaisirs” (Let us love, that the woods may be filled with sighs, That desires and pleasures/ May be the breath of all things”), and the audience sighs along with them, realizing Boston Baroque had presented them with the perfect Valentine card.