Claude Lorrain Landscape Drawings from the British Museum at the Clark

A beautiful exhibition of Claude's drawings, etchings, and paintings not to be missed.

By: Michael Miller - Feb 16, 2007

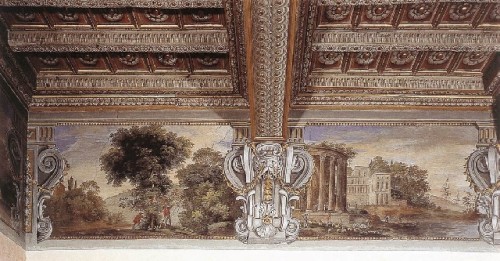

Here in the Berkshires an exhibition of Claude Lorrain, "the Raphael of Landscape-painting," as Horace Walpole called him, brings his work into especially sympathetic surroundings. The view from Pine Cobble, the steeper faces of Mt. Greylock, or its splendid waterfall remind us readily enough of the grander sights sketched by Claude and his fellow artists on their forays into the Roman Campagna. This natural beauty even nurtures a predilection for landscape, so that local galleries can subsist on landscapes, purveying local views for local walls. Even the Clark is susceptible, if you look over the exhibition schedule of the past few years, in which landscapes or seascapes by Klimt, Calame, Courbet, and Turner have been prominent. Far from cloying, or betraying undue self-absorption, Claude Lorraine: €"The Painter as Draftsman Drawings from the British Museum enhances this harmless local obsession with a comprehensive and coherent view of an artist whose cultural importance is undeniable, however one might discuss his stature as an artist. Claude's influence has extended beyond art— among certain classes of British society, at least—into the shaping of whole environments and human life within them. He became so popular that convex tinted mirrors called "Claude glasses" were devised and sold to travellers on the Grand Tour, who, turning their backs to the prospect itself, could look at its reflection in the mirror and see it transformed into something like a Claude painting. The Clark presents the exhibition, as if its justification and the artist's greatness were above question, echoing his most devoted admirers. My own personal response to Claude is spontaneous and affirming, and I am inclined to agree. Yet, I suspect that it is the less reverent critics who have led us deeper beneath the surface of these quiet masterpieces. But more of that later. There is no doubt that the Clark is to be thanked warmly for this handsome exhibition, which combines 90 drawings and 9 etchings from the British Museum, and 13 paintings from various institutions, including the Clark itself.Before Claude landscape appeared mainly as the background of paintings in which the figural subject was primary. Landscape also had a place in fresco decoration, as ornamental interludes in larger schemes in which narrative or allegorical subjects occupied the primary fields—a speciality of Claude's teacher, Agostino Tassi. In the later sixteenth century Annibale Carracci took a step towards giving the landscape greater prominence in relation to the figures, and various northern painters—most of them residents of Rome—painted landscapes in which the narrative subject was even vestigial. However, these were small in size and relatively unimportant. Part of their allure, even, was the inherent paradox of viewing a vast landscape painted on a small support, often less than a foot wide and constrained by a massive frame. Claude transformed the genre, endowing it with a new grandeur, not only by painting larger pictures, but by subordinating detail and incident to a harmonious overall design and an all-encompassing light. Through the mood of a particular time of day, often crepuscular, and the gestures of the diminutive figures inhabiting the landscape, the viewer is drawn into the picture, as if it were a timeless dream. This new way of presenting familiar motifs appealed to the most important and wealthy collectors, and, already in the early 1630's, when he was still at the beginning of his career, he was able to claim and keep a position almost equal to that of the greatest narrative and religious painters for the rest of his very long life—that is, for over forty-five years.

The great extent of Claude's career is one of the more remarkable things about him. By his death in 1682 (In spite of ill-health he was able to work up until the end.) not only had his first patrons died, but also his younger colleagues and competitors, like Gaspard Dughet and Salvator Rosa, who became almost as ubiquitous a fixture in the English country house as Claude himself. Astonishingly, Claude's creativity never became tired or routine over all this time, although he adhered to the same genre and a limited range of variants throughout—and his critics have not failed to point that out. The Clark exhibition tells us less about how Claude's style and technique developed than about the range of Claude's subject-matter—the typology of his landscapes—and how Claude went about developing them.

Using the landscape of the Roman Campagna as raw material, Claude created a recognizable, but non-existent world, one disconnected from seventeenth-century Rome and its business by a timeless quality, suggested by the attributes of extreme antiquity, whether it was the Temple of the Sibyl on its vertiginous perch at Tivoli, the half-buried ruins of the Roman Forum, or pristine forests and fields inhabited by cattle, sheep, goats, shepherds and other country-folk in appropriate classical dress. There is no denying that there is an element of escapism in Claude's aesthetic. He produced many of these paintings at a time when the popes, especially Urban VIII (1623-44) and Alexander VII (1655-67), were making strenuous efforts to modernize the city of Rome. Lievin Cruyl's anticipatory views (published in 1666) of a Rome transformed by Alexander show a cleaner, more salubrious, more rational city, its grandeur vaunting the latest inventions of Borromini. Traces of the old Rome, where vast tracts of pasture land were enclosed within the ancient city walls, were hardly to be seen. As Richard Rand observes in the catalogue, Claude rarely represented the buildings of modern Rome. His black chalk view of St. Peter's from behind, in fact, shows the fields behind the basilica, complete with cow, cowherd, and haystack. Claude lovingly depicted this old Rome in his 1636 views of the Campo Vaccino (or Cow Pasture, as the Roman Forum was called at the time) which are included in the exhibition and amply discussed in the catalogue.

Claude turned his vision away from the city of Rome to the Campagna, where little changed. However, his Campagna was a green, wooded land, an Arcadia which resonated for Claude and his patrons through ancient and modern literary associations and the dim recollection of a Golden Age, or perhaps beyond that to primeval times, when primitive man inhabited the forests. Claude and his patrons knew perfectly well that the deforestation of the Campagna (as well as much of the Mediterranean world) was already disastrously advanced in ancient times. Familiar classical texts of all kinds mentioned it: Livy, Pliny, Strabo, Columella, poets like Vergil in his Eclogues and Georgics, even Plato.*

If trees were scarce, so was shade, and ancient poets made much of this cooling luxury, as did Claude. His predilection for sunsets and late afternoon light, when even the poor shrubs of the Campagna of his day cast long shadows, echoed the mood of the Latin pastoral verse which was so much a part of his patrons' culture, in particular the famous closing verses of the last of Vergil's Eclogues:

Let's get going. Shade has its way of harming the voice.

Shade is hard on juniper, and shade is bad for crops.

Head home now, she-goats! You've eat your fill.

The evening star is coming. Head home.

The use of light and shade and the color of a particular quality of light to convey a sustained mood was one of the ways in which Claude was most truly himself as a painter, but it was also one of the ways in which he meshed with the larger culture of his time. This understanding of light and the ability to render it in paint or wash did not come easily. Claude's first biographer, Joachim Sandrart, spoke of the pains he took in studying light, "lying in the fields before the break of day and until night in order to learn to represent very exactly the red morning-sky, sunrise and sunset and the evening hours." (cited cat. p. 64) If he wanted to record the colors of light and atmospheric effects, it was of course a ponderous process to prepare the colors in the open air and return to the studio to paint. Sandrart claims that Claude learned to paint in the open air from him and that he executed many small paintings of this sort. None, it appears, survive, although a small painting of a Landscape with Goatherd and Goats from the National Gallery, London has been proposed as a possible candidate, because it corresponds in some ways with a work described by Claude's second biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, it seems too finished to have been executed en plein air, complete with a rather classical reclining goatherd and his carefully arranged flock, as Rand quite sensibly concludes (cat. pp. 66-8).

Drawing from nature is the point of departure for the exhibition, which begins with a room devoted entirely to a painting, an etching and several drawings, all of which show a draftsman at work in the foreground. Claude's was not the romantic age. In these the draftsman is always in the company of at least one animated companion, who either gestures in admiration at the artist's work or at the prospect itself. (However, Claude did represent solitary draftsmen elsewhere.) While, on the one hand, they document the basis of Claude's work in drawing from nature, their effect on the viewer is to provide some human intermediary, with whom he can identify. This brings him into the landscape, whether it is a large canvas or a small etching, and enables his full participation in the scene. In all the works in the show, only the detail studies of trees, rocks, and streams lack these human mediators. Their pointing gestures, as in the Tomb of Nero later in the exhibition, embody the full experience of the act of vision with all its attendant emotions.

However, I am wandering from the argument of the exhibition already...but the works themselves convey so much more than that! The function of this room is to stress that Claude based his art on the study of nature. The next room, titled "Drawing from Nature" continues, showing us the different kinds of studies Claude made in the field. There are distant views of mountains and valleys, as well as towns and villages. In spite of Rand's reservations about its relation to open-air painting, the Goatherd mentioned above is hung in this group. From there we progress to studies of individual trees, natural and human scenes in the shade of trees, shade and shadows, rocks and water. Over this range of natural subjects, we appreciate the range of technique Claude had at his disposal—pen combined with wash on cream paper, extremely fluid wash by itself, pen, ink, and white heightening on blue paper, and combinations of tinted heightening and wash—and how he was able to use them to evoke the ocular impressions of these natural objects. While Claude's perceptions are sensually vivid, they are by no means detailed at a botanical or geological level. (It is worth noting that botanist-draftsmen like Gherardo Cibo had already gone far in developing that sort of scientific observation, which in itself produced wondrous results.) The small View of La Crescenza, the most informal painting in the exhibition, which shows a close connection with study from nature, hangs here.

Next to this you will find one of the most impressive rooms in the show, devoted to a closely-knit group of drawings and two paintings of Tivoli, as well as other field drawings from high mountain viewpoints. I strongly recommend taking the time to examine all of these closely, because, after the immersion in Claude's nature studies in the previous room, you can see how Claude observed Tivoli on his visits and later transformed the raw material in his working drawings and finished paintings. It is especially valuable to see both versions of the scene together, one more instance of the intelligence and thoughtfulness of the selection.

A large gallery follows, "Landscapes Old and New," devoted to Claude's studies of ruins and other ancient monuments in and around Rome, as well as his idealization of natural scenes of shepherd life in "Arcadia," a poor and backward region of the Peloponnese, the home of the god Pan, which in both ancient and renaissance pastoral poetry became of the typical locality where people lived simple lives, close to nature. This is of course a subject quite distinct from the antiquarian contemplation of ruins, but in relation to Claude the association is a fruitful one, since his studies of ruins are more contemplative than scientific, the very opposite of the meticulous studies found in the contemporary Cassiano dal Pozzo album, to which his friend Nicolas Poussin may have contributed. This room includes Claude's painting, drawings and prints of the Campo Vaccino, a group, which, like the Tivoli room, will reward extended study.

The first room of the next main section, "In the Studio," is dominated by Claude's large, rather formal composition, Nymph and Satyr Dancing, as well as drawings illustrating his work in the studio, the process by which he transformed his nature studies into finished paintings. There are splendid finished working studies and sheets from his Liber Veritatis, an album of drawings after his finished paintings, which he maintained since the mid-1630's, when he was commissioned to paint a group of paintings for King Philip IV of Spain, a sure sign of his success. Supposedly he kept the records to prevent forgeries, but he put much care into making them as beautiful as possible and often developed a somewhat different interpretation in them, so that we must regard it as part of his creative process. Moreover, since the specific subjects of his landscapes were often types, and were subordinated to the natural environment, he surely needed some way to keep track of his inventions, if only to avoid inadvertent duplications.

You will also see an example of Claude's unique kind of "grid," which he used in his finished compositional studies. While painters traditionally squared their finished model drawings for transfer to a full-sized support, Claude used lines radiating from a point at the center of the sheet. Since he laid these in before making the drawing, it may be that he used them in compositional construction as well. His process is not fully understood. His landscape were made up of successive planes of receding ground, and sometimes there are multiple vanishing points, particularly if the composition includes different levels. In this case a squared grid could have proven counter-productive, making it more difficult to avoid the sort of rigid linear design of the inferior practitioners. This looseness of perspective and design lays behind much of the unique quality of Claude's landscapes.

The grand Nymph and Satyr points to another interesting trait of Claude's art. In the serene reclining female onlooker, modeled on classical precedent, her bare torso, seen from the back, is about a close as we get to nudity in his paintings. Landscapes with nude female figures—bathing nymphs or Diana and her entourage—were extremely popular at the time, and several of Claude's contemporaries made the most of this mild eroticism. Claude's chaste approach to the nude was clearly due not only to his notorious lack of skill in human anatomy, but also part of the serene dignity of his style...and perhaps it does reflect a certain prudishness. In this work the dance is in fact an initiation to love, evident in the tentativeness of the young nymph as she takes her first steps with the rather galant satyr.

The inter-relationship between technique and subject-matter continues in the next sub-section of "In the Studio," which combines harbor scenes, storm-tossed ships, and nocturnes, a genre developed by Netherlandish artists, reminiscent in effect of the candlelight scenes of Claude's compatriot from Lorraine, Georges de la Tour (1593–1652). We also see the large painting, the Judgement of Paris of 1645-46. The classicizing figures come from Raphaelesque models with reminiscences of the Carracci and Domenichino. Again there is hardly a trace of sensuality in the paradoxically disrobed Minerva, who discreetly covers her torso as she bends over to tie her sandal. These figures, more prominent than usual in Claude, who suggest classicism without conforming to its proportional norms or reflecting its grace, are still not unpleasing and make a resonant harmony with the landscape.

The mythological scenes of the penultimate room, mostly from the 1640's and 1650's, show Claude's discretion in presenting violent, gruesome, or grotesque details. The Coast Scene with Acis and Galatea shows the lovers in a happy moment before their tragic end. In the drawing and etchings of Mercury and Argus, the thousand-eyed cowherd is humanized, showing only a barely noticeable third eye in the forehead. In these the naturalism of the dominating landscape overpowers any fantastic elements in the myths. On the other hand, in the contrasting biblical scenes, that is, Christ Preaching on Mount Tabor, Claude abandons his naturalism in favor of a fanciful hill, reminiscent of earlier northern artists like the younger Brueghels and Brill. You will also see two drawings for Claude's lost masterpiece, Queen Esther at the Palace of Ahasuerus, one of his most elaborate essays in architectural fantasy. In them we see Claude working intently with the figures, their gestures and their place in various architectural combinations, in order to arrive at the most dramatically pointed representation of the narrative.

The final room concentrates more on subject-matter in relation to the later years of Claude's career. So far the exhibition has avoided paying much attention to chronology and development, combining works of different periods within one section, and here, too, works of the 1660's are combined with works of his last five years. Mythological narrative, especially scenes from Vergil's Aeneid, comes to the fore. One can only wonder at the almost frigid beauty of the vertical Landscape with the Temptation of Christ on blue paper, or the warm, expansive pen and brown wash drawing of Aeneas and the Cumaean Sybil, both of 1677. As in previous rooms, carefully chosen comparisons of different treatments in preparatory drawings, reveal much about Claude's thinking. His method of developing strongly contrasting compositional studies with pen, brown ink and wash on cream paper and with pen, ink and heightening on blue paper, reveals much about his process of invention. He finds it necessary to imagine the scene in differing ways before proceeding to his final solution.

There is also the very beautiful Pastoral Landscape from the Kimbell Art Museum, painted for Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna in 1677. Rand observes that this is "the only work by Claude in Colonna's collection that does not have a clearly identifiable subject," and he goes on to cite various speculations on sources in the Bible or early Roman history. The answer may not be so difficult. The sitting and the standing shepherd are clearly engaged in a friendly singing contest like Mopsus and Menalcas in Vergil's Fifth Eclogue. While the three female accompanists do not appear in Vergil's poem, and the location is not a grotto, but a secluded spot in the open air, this could well be an adaptation of Vergil's treatment, or perhaps there is a more exact correspondence in one of the many renaissance or baroque imitations, like Sannazaro's in his Arcadia, his Eclogues, and his Elegies.

Dominating this final room and fittingly bringing a close to the show is his monumental canvas of Apollo and the Muses on Mount Helicon, which he painted the year he died. A reminiscence of the temple of the Sibyl at Tivoli appears atop a somewhat fanciful mountain, and the figures, in spite of their odd proportions and ungainliness in relation to the landscape and each other, seem somehow perfectly convincing as denizens of this divine place, as swans swim placidly in the pool below.

In order to point out its most important themes, I have mentioned only some of the works in an exhibition of such quality that it defies any isolation of highlights. I urge you not only to go the the exhibition, but to go many times, and to delve deeply into the range of Claude's work and methods. Its organization couldn't be more conducive to enlarging one's understanding and enjoyment just by looking.

On the other hand, Richard Rand's principle of organization was not so propitious for the catalogue. The fact that catalogue and display correspond shows that it was thought out carefully in advance, of course, but as a reader I could not avoid feeling some frustration. Following the argument I have outlined, the catalogue consists of a long essay by Rand, with illustrations of varying sizes within the text, some rather small for their importance. The works listed one by one in a hand-list at the back, but their order corresponds neither to the arrangement on the walls or in the text, severely limiting its usefulness, especially since there is no numbering. It is intended that we read the essay from beginning to end (which I did), and this unfolds the topics mentioned above through extremely painstaking visual analyses of each work. While I could navigate the text easily enough by referring to the illustrations, the deliberate avoidance of chronological organization actually made for quite a lot of repetition, and if a particular bit of information does not fall in the vicinity of the relevant illustration, if becomes difficult to find. What's more, there is no index.

Before discussing the catalogue any further, I should point out the great dilemma in Claude studies. Most of this exhibition consists of drawings and prints from the collection of the British Museum, over 500 drawings, that is, almost half of Claude's extant drawings. Part of these came early to the museum from the bequest of the important collector and critic Richard Payne Knight, the rest, primarily from the Liber Veritatis, came in the mid-1950's from the collection of the Dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth, as a donation in lieu of death duties. Back then Chatsworth was not as accessible as it is today, and the arrival of the Liber, which provided an invaluable framework for chronology, in a public collection created a scholarly revolution. Two scholars, Marcel Roethlisberger and Michael Kitson, independently set to work on the material. In the early 1960's Roethlisberger published catalogues raisonnés of the paintings and the drawings, and Kitson many essays on specific problems. Together, they did an excellent job of laying new foundations for our understanding of Claude, establishing criteria for attribution, chronology, and identifying subjects and patrons. They both continued to develop their work in subsequent years, and in 1982 H. Diane Russell curated a major exhibition which summarized the achievement of the past quarter century and added still more. Although she mentioned outstanding problems of chronology, patronage, and technique in her catalogue essay, Claude studies fell into a lull after this, and comparatively few new scholars have come to the field since then. The thoroughness and intelligence of what was accomplished then has provided a solid foundation, but also little to dispute. Jon Whiteley's excellent 1998 exhibition of 100 drawings and etchings from the Ashmolean and the British Museum (with a conventionally organized and very useful catalogue!) found it necessary to devote much space to summaries of the sound wisdom of Roethlisberger and Kitson, as does Richard Rand in the present catalogue.

It is usually difficult to justify an exhibition like this if there is not an active community of scholars to contribute and to create a forum for discussion, but North Americans have not seen Claude drawings since 1982 (beyond the Morgan Library's occasional presentation of their own substantial holdings) and the mere opportunity to see these splendid works in a coherent context justifies itself. Richard Rand can only be thanked for taking on the job of compiling yet another summary of the results of that golden age of Claude scholarship, which he does judiciously, weighing one view against the other and never interjecting his own opinion when the received ones are satisfactory. His own point of view appears in his tight focus on Claude's method and typology, topics already stressed and discussed by Whiteley in 1998. (His introduction shares several topics with the present catalogue, e.g. "Drawings from nature," "Tree studies," "Excursions," "Drawings for and after Compositions") Here again Rand's approach is thoroughly sensible and founded on his close examination of the drawings. I found myself disagreeing with his observations or conclusions only occasionally, usually in cases where his intense engagement appears to have led him into a cul-de-sac, for example, in the vertical study of the tomb of Cecilia Metella (pp. 110f.), in which the monument is observed beyond a massive foreground rise topped by vegetation. After an excessively intricate analysis of a basically straightforward field study, modified perhaps in the studio (or perhaps not), he concludes that the three elements of the scene were "drawn at separate working sessions." This would be unusual, but not impossible. Perhaps Claude broke off for lunch and had a bit too much wine. That is all we can say. This is one example of a general tendency to over-analyze. There is no question that the catalogue would be more manageable—and useful—if it had conventional entries for each work and a concise introductory essay with a few well-chosen analyses to support focused arguments. I found myself all too often plowing through the discussions expecting a conclusion which never appeared.

Also a sharper critical attitude might have brought more pith to the surface. Even Claude's early admirers found shortcomings and limitations in his art. After a negative period in the nineteenth century we find Roger Fry in his 1907 essay (still one of the most perceptive evaluations of Claude's work) striving to rehabilitate him with some fairly "tough love." In the present catalogue we encounter the word "beautiful," "pleasing," "pleasant," and other uncriticized and uncritical terms of appreciation much too often. There are also signs that the edge of more contemporary jargon is growing dull, when we read "Its [St. Peter's Basilica's] symbolic presence as a signifier of the reach of Papal power in the landscape was no doubt significant as well." (cat. p. 104)

The discussion of literary associations, an important topic for Claude, is another weakness in the catalogue. For example, describing Horace's very interesting connection with Tivoli by saying that he "wrote his Odes at his farm in the Sabine mountains just nearby" is not terribly helpful. Horace did in fact spend a lot of time on his farm, but he wrote his odes in several working cycles over a number of years, and he must have worked on them in other places as well, not to mention that he may possibly have acquired a second villa in Tibur itself. (The debate over this is one of the more charming whigmaleeries of Horatian studies.) Also, Sannazaro's Arcadia is not a poem, but a pastoral novel in prose with lyric interludes, like the work it inspired Sir Philip Sidney to write. These points are small in themselves, but Claude painted for a clientele who read and loved these authors, and nothing can benefit our understanding of Claude more than an informed appreciation of the culture in which he lived.

This, in conclusion, brings me to the most serious sortcoming of the exhibition as a whole. We learn much about his drawing methods and we are given the opportunity to consider them in relation to a selection of his paintings, but, especially in an exhibition intended for the general public, this point of view is extremely narrow. It is important to consider his achievement in the context of a learned society which studied antiquity and nature, read classical and modern authors, built villas and gardens, saw plays and operas, and sung madrigals. Furthermore, Claude studies have so far have put him on a lofty, isolated pedestal above his contemporaries, but, as we can still observe in the great Roman collections which have remained intact, his patrons collected his landscapes along with those of his most eminent predecessors and contemporaries. Where we find Claude, we find Brill, Tassi, Dughet, Rosa, Poelenburgh, Cerquozzi, and others. An extra section with a dozen or so works by Claude's predecessors and contemporaries would have been a marvelous addition to an already splendid exhibition.

___

*Wood was already scarce before classical Greece. Thucydides in his account of the Peloponnesian War shows the Athenians' desperate need for wood, not least to build warships, and how it was one of the chief motives for the disastrous Sicilian Campaign, a military debacle anyone concerned about American exploits in the Mid-East should study. Even in a relatively straightforward view of a country estate, La Crescenza, painted for a relative of the family that owned it, Claude managed the vegetation to make the land appear as green as possible, and this is a far cry from the ideal views of Tivoli, represented by two paintings and several drawings in the exhibition, which represent the essence of Claude's transformation of familiar monuments and localities into ideal, timeless places. As you examine the numerous paintings and drawings of this sort in the exhibition, you will frequently notice the presence of goats, usually lively and obstreperous. Most of Claude's patrons would have had sufficient classical learning to know that the ancients considered the omnivorous goat as a dire enemy of trees and all sorts of plant life. By giving them such a prominent place in his compositions Claude literally depicted the "gnawing tooth of time" that destroyed this paradise. Not unlike their descendants of the Baroque era, extremely wealthy Romans created artificial forests, silvae barbaricae, with many different species planted in disorder to recreate the primeval landscape. The famous epicure Hortensius had such a park extending over 33 acres, where he entertained his guests by calling wild animals for feeding, while a servant dressed as the primeval poet Orpheus played the harp and sang.

Author contact: mjmiller@thedrawingsite.com web http://www.thedrawingsite.com