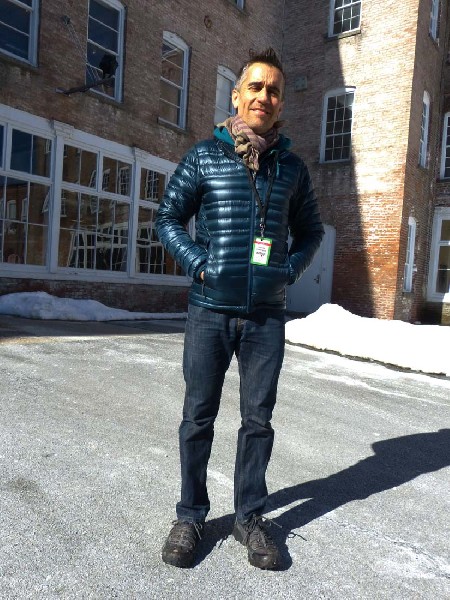

Darren Waterston at Mass MoCA

Deconstructing Whistler's Peacock Room

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 14, 2014

The mid career artist, Darren Waterston, was invited to create a large work for a year long exhibition at Mass MoCA. After considerably thought and research he opted to create a technically complex, unique, labor intensive recreation and surreal deconstruction of Whistler’s iconic masterpiece The Peacock Room.

Since July the artist has rented a loft in the Eclipse Mill in North Adams while working on the installation. That makes him a neighbor although we met only recently on the day of a visit to the work in progress. It is a comment on mutually busy lives that our paths crossed serendipitously in the Mill’s parking lot while the artist was walking his two dogs.

He managed to carve out a half hour to talk with me. Until the opening on March 8, then just a couple of weeks away, he has been on a fifteen hour daily charrette.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (July 11, 1834 – July 17, 1903) is one of a handful of most important American artists, like Mary Cassatt, because he opted to spend his entire adult life and career in Europe. Starting in Paris where he enjoyed initial success he moved to London which he left having lost law suits to recover fees owed him by Frederick Leyland for The Peacock Room, as well as, a costly libel suit against the critic John Ruskin. In poverty in Venice, as was his wont, he lived on the kindness of strangers. In this case the artist Frank Duveneck and his students.

While one of the foremost American artists of his generation he was also a bounder and scoundrel notorious for his acerbic wit. He falls somewhere between the grand camp of Oscar Wilde and the misanthropic Edgar Degas. Significantly, in 1890, he published The Gentle Art of Making Enemies largely inspired by the transcript of the Ruskin trial.

It was particularly interesting and insightful to discuss with Waterston how Whistler inspired him to create such a complex and elaborate homage. Through this year and a half process of channeling the artist on a daily basis what had he learned about Whistler?

Darren Waterston The exhibition is called Uncertain Beauty. It’s a combination of a survey of paintings and works on paper from the past couple of years and a major installation as a centerpiece. This is called Filthy Lucre.

Charles Giuliano Whistler’s Peacock Room. A kind of busted up Peacock Room.

DW This is a project that Mass MoCA has built and created. It is completely 100% Mass MoCA certified work of art.

CG Unfortunately the walls are not Moroccan leather as was the case in the original. (Whistler painted over the 16th-century Cordoba leather wall coverings first brought to Britain by Catherine of Aragon for which Frederick Leyland (1832 – 1892) paid £1,000.)

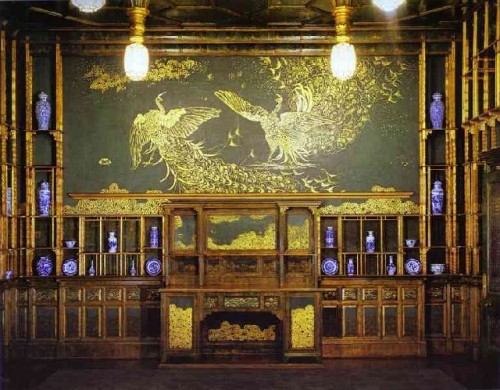

DW We’re assimilating them. The whole idea is that we’re creating a parody. A sumptuous ruin of the original Peacock Room. Leyland, the owner of a London mansion, was very close to Whistler. He was the main patron of Whistler and had commissioned all kinds of works from him. He was a real advocate of the work and had commissioned the painting (The Princess from the Land of Porcelain) which was to reside over the fireplace of his dining room. The room also housed his very important collection of ceramics or porcelains. He employed the most important interior designer of the time Thomas Jeckyll (1827-1881).

Leyland spent a huge amount of money on the room including the late Renaissance, hand tooled leather walls. There was all this elaborately carved lattice work to house the porcelains. There was also an elaborate ceiling.

CG Then he went away on vacation for three months.

DW You know the story so I don’t have to tell it to you.

CG But I would love to hear it from you.

DW He went away on vacation and Whistler…

CG Moved in.

DW He was directed to only change a few of the colors of the petals of the original leather tooled walls to integrate more with Whistler’s painting The Porcelain Princess which was hanging in the room. He was given directions like ‘Can you use a light touch and please add a few colors to pull it all together.’ Whistler who was very grand…

CG Indeed.

DW And entitled. A wildly megalomaniacal guy. He just decided, no, I want to make this room something else. I want to honor my painting and the collector is going to love it. Uninvited and unsolicited I’m going to make a work of art. He locked himself in for three months.

CG And invited people in for private viewings of the work in progress. He had cocktail parties.

DW All of it. He wanted lots of publicity. He was inviting the literati and London society to come and create a buzz.

CG Actually, like Whistler, I hear that you have a salon at the (Eclipse) Mill.

DW That was only once.

CG Your fame precedes you. The buzz is that this is the work that will make you famous.

DW I wish.

CG People are getting excited about it.

DW It’s been good.

CG And it’s going to travel.

DW It goes from here to the Smithsonian where the original Peacock Room is. The original room was bought (from Leyland’s heirs) by Freer an early industrialist.

(The Freer Gallery was founded by Detroit railroad-car manufacturer and self-taught connoisseur Charles Lang Freer. In 1908, Charles Moore, a former United States Senate aide, moved from Washington, D.C., to Detroit. Moore became friends with Freer, who was director of the Michigan Car Company, and persuaded Freer to permanently exhibit his 8,000-piece collection of Oriental art in Washington, D.C. Before then, Freer informally proposed to President Theodore Roosevelt that he give to the nation his art collection, funds to construct a building, and an endowment fund to provide for the study and acquisition of "very fine examples of Oriental, Egyptian, and Near Eastern fine arts.")

Freer was a great fan of Whistler. He bought the room. The painting had already been sold as well as some of the objects. He bought them and pieced the room back together with great effort. He had it shipped to Detroit where he lived. It was reconstructed in his home. At the end of his life he bequeathed it to the Smithsonian. Actually his entire collection.

This will be installed in the Sackler Museum which is adjacent to the Freer. It’s able to accommodate the space.

CG What possessed you to do this?

DW I was invited by Mass MoCA to do a very large scale painted room. It was going to be an ephemeral, site specific piece. That was the original invitation. Then I thought this is my one exhibition at Mass MoCA in my career. So let’s go for it and do something ambitious.

Then I thought, what are the great painted rooms, and wanted to reflect on how they came about. What inspired an artist to paint an entire environment?

CG Why Whistler?

DW It wasn’t necessarily Whistler. It was The Peacock Room. I remember knowing about the room but I had never seen it. I didn’t know that much about it.

CG What time frame are we talking about?

DW A little over a year ago. Maybe it was 18 months ago. It was 18 months ago that I started investigating and a year ago when the museum and I decided on the project.

CG Was there an epiphany when you walked in and saw it?

DW Not an epiphany but relief. I had been studying so intensely as a novice scholar. Trying to find everything I could about this room, its history and Whistler. Then I thought what if I see it and it’s disappointing. That was the fear. I wasn't sure if after all this effort I walked in there and it was kind of eh. But it was the opposite when I walked in for the first time. I thought ‘Oh My God.’ It’s already so grotesque, excessive and wonderful.

CG The Peacock Room backfired on Whistler. When Mr. Leyland came home he refused to pay the excessive bill for work he had not approved. The controversy started his downfall.

(The Peacock Room was painted in 1876-77. In 1877 Whistler sued the critic John Ruskin for libel after the critic panned his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rockets. Ruskin reviewed Whistler's work in his publication Fors Clavigera on July 2, 1877. “For Mr. Whistler's own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay [founder of the Grosvenor Gallery] ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of willful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face.”

Whistler won the case but was awarded a farthing. The court expenses, which were excessive, were split. It resulted in bankruptcy for Whistler and a mental breakdown for Ruskin.)

DW When he lost the lawsuit which resulted in the loss of his home he was so devastated. It was more that his ego was bruised. So it’s not so much that it resulted in his demise as that it took the wind out of his sails. But The Peacock Room was the singular achievement for which he is best remembered as well as the portrait of his mother.

CG Also Courbet seduced his girlfriend (Joanna Hiffernan) when he traveled to South America to take part in a civil war. So he had a lot of bad luck.

DW And a lot of good luck as well.

CG He was expelled from West Point which saved him from fighting in the Civil War. Actually West Point was one of the first to teach fine arts. It was considered part of the education of an officer to be able to make field sketches and maps of terrain. His father had taught drawing there and Whistler studied with the painter Robert W. Weir. It was at West Point that he learned drawing and painting before his study in Paris.

DW You know he was born not far from here (Lowell, Mass.)

CG He denied that.(At the Ruskin trial, Whistler claimed St. Petersburg, Russia, where his father was employed as an engineer, as his birthplace: "I shall be born when and where I want, and I do not choose to be born in Lowell", he stated.) Do you plan to visit Lowell?

DW Yes. I want to see The Whistler House. Once I put down the paint brush I’ll go there.

CG You’ve been here since the summer.

DW Yes I got here in July and we’ve been working non stop.

CG You told me that you plan to pull fifteen hour days between now and the opening on March 8.

DW This is so involved and there is still so much more to paint. There’s surfaces and glazing as well as all the objects that go in here. There are 250 vessels. I collected them throughout the region here and I’ve painted them. They have some reference to the original collection, their shapes. They are sort of orientalist in form. They were all gessoed, primed and hand painted. They are more like little paintings than looking like the original collection.

CG What’s with the disarray. Why are we seeing the room decomposed.

DW It’s the idea of all of this excess caving in on itself. The idea of consumption and opulence.

CG How much are you caught up in that? Are you decaying, decrepit and falling apart?

DW At 48, yes, absolutely. (With ironic humor.)

CG Is this a metaphor of your rise and fall? Is this your Phoenix story or just a dead bird in the ashes?

DW There’s no personal narrative that I can attach to it. At all. Whatsoever. Obviously I’m very connected to the project but there’s no personal narrative for me. It’s been transformative in so many ways. More than anything the collaboration. Working with this extraordinary museum. Everyone who has a hand in this it’s all artists. The entire team of fabricators here, every single one is an artist. They think like artists.

CG How many are in the team?

DW Maybe fifteen.

CG Did you know them before the project?

DW No we all met here. Everyone lives here. More than anything it’s the museum’s fabrication team which is on staff. Mainly Richard Criddle and Derek Parker a local artist. He’s the one who has spearheaded the whole project.

CG How close is this to the dimensions of the actual room?

DW It’s close in every detail but exactly 10% smaller. Because we had to clear the height.

CG Who created the plans?

DW A recent Yale architecture graduate, Danny Greenfield. He took all of the original drawings we had from the Smithsonian. We had to interpret everything. We had to figure out as close as possible how to design this. We also had to design a modular system because it all has to break down in order to travel. That has created a whole lot more labor intensive planning around the project.

CG Where there archives at the Smithsonian?

DW Yes. A lot. I worked with the curator at the Smithsonian, Lee Glazer. She’s the gatekeeper of the Peacock Room and the main scholar. She is also contributing to the catalogue. She has been enormously supportive and has kept feeding me information.

CG What kind of material is there?

DW Drawings, sketches.

CG Are there any architecture drawings?

DW No. Nothing. It was all sketched out on little pieces of paper. It was all impromptu.

CG Did he have assistants?

DW No. He did it all himself in about three months.

CG Mr. Leyland had the option of remove everything and take it back to its original appearance.

DW He didn’t want to pay for it but actually he loved it. He had breakfast every morning in the room facing the mural that Whistler painted of the two fighting peacocks. The peacocks were the last part of the room. When the fighting had already started Whistler got permission to come back and finish the project. While they were in a debate he said “Let me finish the room.” He was granted permission while all these tensions existed. That’s when he painted the peacocks.

CG This project is so totally absorbing are you anticipating an emotional letdown when it’s finished.

DW No. There’s no time for that. I immediately have to start painting for my exhibition in the fall at D. C. Moore Gallery. I will have a little bit of breathing time. I’m also teaching at Williams College this semester.

CG Are you painting here?

DW Yes. I have a studio here.

CG Are you getting any work done?

DW I am actually. I have to. Because my other work is my livelihood. This is not.

CG It doesn’t pay the bills but it makes you famous which helps to raise the prices. It’s an interesting process for artists who do large installations such as this and biennial projects. The site specific pieces are so expensive and labor intensive. Sometimes there is fund raising and grant writing involved then little prospect of selling the resultant work. As a career strategy they assist the artist in other way

(Christo, for example, sells plans and studies for projects which raises money for other projects.)

So what does it mean for you to carve out a large amount of time (18 months) to execute a project that may or may not result in its sale.

DW Maybe. But I wasn’t thinking that strategically. It was more like I want to do this. It’s going to be great.

CG So it was about passion.

DW Absolutely, 100% driven by it. I also had no idea that it would have this level of finish and become a thing that was so complete and realized at this level. Again that’s back to Mass MoCA because there was a point in the process where Susan (Cross the curator) was like people are going to have their noses up to every surface. It is all very unforgiving. You really have to do it at this high, high level of finish. It’s not a theatrical set. It’s a work of art. Every surface is painted.

CG What state is it in right now?

DW We’re getting there. Something happens in the next couple of weeks when it is assembled. I go through all of it and add paint and glazes. Pouring paint off the ceramic vessels to create puddles. So that it looks like the glazes are melting and creating puddles on the floor. Broken ceramics and paint all over. Glaze all over the walls.

CG So it’s a surreal fantasy piece.

DW Absolutely.

CG Not a reproduction.

DW No. Not at all.

CG You’re taking it to another place. Does that legitimize your ownership?

DW It’s a delicate balance. It’s between not wanting to create a parody or facsimile but wanting to interpret and interrogate it. To change it into something else.

CG Appropriating and copyright are important issues in contemporary art. Perhaps the ultimate example was Sherrie Levine photographing images by Walker Evans and exhibiting them as her own. You are making an editorial fair use of the work but it places you somewhere along the trajectory of the appropriation debate. Of course the artist is not alive to sue for infringement. I assume you are not going to be sued by Whistler who is long dead. What do you have to bring to this to claim it as your own original work?

DW Most of my work of the past 20 years has been based in historical references. Working alongside paintings, sculptures, installations and environments which contain experiential places of contemplation. I chose this room as an homage to the artist. As well as a point of departure where I could actually explore a different point of view around the painted room and still referencing this very particular room. There is the ambiguity of authorship as well as all the individual hands which have made marks in this space. There has been so much input by so many incredibly talented artists. I feel like we’ve come up with something that’s very particular and unique. Still again it’s a direct reference to this very specific and important work. I’m very interested in the tension between the beautiful and the grotesque. How something aesthetically pleasing also has an underbelly. Looking at the play of the ambiguity between the the beautiful and lush then where it becomes deformed and monstrous. So this is the perfect thing to play that out.

CG You’re an artist and not an art historian. You have been involved with the Whistler project now for 18 months. What do you know about the artists that you didn’t know back then?

DW What I didn’t know then is how incredibly driven he was. What a cunning business person he was. The ways in which he wanted to survive as an artist. The way that he cultivated relations with patrons. The way that he figured out a system to survive. It’s a very contemporary dilemma as all artists are in a constant contradiction of how do you make your art and sustain yourself as an artist. At what cost? And how do you cultivate a context for all that.

CG Whistler was also brilliant at living on other people’s money and never picking up the check.

DW Absolutely.

CG He left London with a great deal of debt. How about Whistler as an artist? How do you know and respect him?

DW He was incredibly deft as a painter. Before this project I was moved and always lived his Nocturnes. There was an incredible pure abstraction of a night sky and all those paintings of fireworks over the Thames. They are so luscious and beautiful. Those are the works of his that I always loved. This has given me a much more expansive view of the artist. A play between his desire for an aesthetic continuity and design, architecture and painting. All the realms, in a very diabolical way, the way that he would bring these seemingly disparate disciplines together.

CG Somewhat like an actor you have had to get into his head.

DW A little bit, yeah. He’s been around. I’ve got a velvet suit or two. But I already had that.

Link to Debora Coombs Criddle on fabricating ceiling lamps for the MoCA Peacock Room.

Link to Darren Waterston blog.