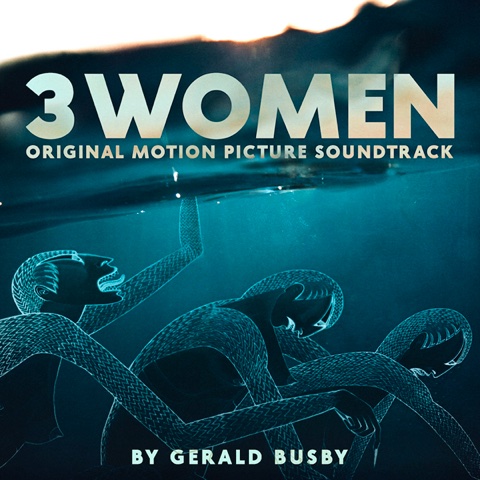

Wave Theory Records Presents 3 Women

Legendary Score by Gerald Busby

By: Jessica Robinson - Feb 07, 2021

Wave Theory Records has released the original soundtrack from legendary filmmaker Robert Altman’s 1977 cult avant-garde film 3 Women, starring Shelley Duvall and Sissy Spacek. The strikingly dissonant score was written by American composer Gerald Busby.

Before films talked, they still made themselves heard through intertitles and musical accompaniment. The psychological theory behind having music accompany ‘silent’ films is, so film scholars believe, that watching actors speak with absolutely no sound makes an audience feel, “unalive.” So, to keep movie-goers from feeling ‘dead’ there would be live accompaniments by a pianist, theater organist, sometimes even a small orchestra, playing either from sheet music, or improvisation. For the most part, it was just pleasing background music. They often made no effort to match the picture. Indeed, some pianists sat with their back to the screen, playing anything.

It wasn’t until 1933 that movie music was forever changed when Max Steiner, considered the 'father of film music,' wrote an original film score commissioned specifically for an entire plot. The movie was King Kong. For the first time, music did not just repeat what the audience was seeing, but actually revealed what the characters were thinking - one of the most powerful things that film music can do.

Once the ability to synchronize music and sound to celluloid became possible, music quickly became an essential aspect of the storytelling process. Soundtracks help make movies memorable by reinforcing the atmosphere or mood of a film, as well as giving a rhythm to scenes.

Sometimes the music becomes as iconic as the movie itself. Gerald Busby’s haunting score to Altman’s strange 3 Women is a potent example. Released in 1977, the movie starred Sissy Spacek, Shelley Duvall (for her role she won a Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival), and Janice Rule.

Altman said the story came to him in a dream. It is surely dreamlike in its eerie slowness and peculiar atmosphere. It‘s as though it were set in some alternate universe.

The movie opens in a geriatric center as old people slowly walk, back and forth, in an exercise pool. Busby’s ominous, atonal score is a counterpoint to these daily rituals, adding to the unsettling atmosphere.

According to Altman, the opening shot represents the amniotic fluid surrounding a fetus. Perhaps these geriatrics are returning to the water from wherein their lives began.

But what’s it about? Maybe it’s beyond meaning. Certainly the film is mysterious, and Busby’s piercing flute solos and pulsating bass strings add to that sense of mystery.

3 Women is considered Altman’s most poetic, yet enigmatic, film. (If you haven’t seen the movie?—?you must!)

How did an unknown composer who had never written a film score, never conducted an orchestra, land such a plum assignment?

In 1975 Gerald Busby had just composed the score to Paul Taylor’s Ballet Runes. It was his very first commission?—?and, according to him, it had been predicted by a psychic. He would meet, the psychic told him, a man five years older than he was, who was established in the arts, and who would ask him to collaborate on a piece dealing with the occult. And, the psychic added, the work would have its premiere in Europe.

A few months after the psychic’s prediction, Busby met Taylor, the famous choreographer, who commissioned him to write a score for Runes, which opened at the Theatre de la Ville, in Paris, in 1975.

The next year the Robert Altman thing happened.

Busby’s lover at the time was a publicist who wrote press releases and arranged screenings for movie critics. One of his film connections was Mike Kaplan, the full-time publicist for Altman. He knew Altman was looking for a composer to score a film he had already shot, without a script, in the God-forsaken California desert near Palm Springs.

So he sent a tape of a solo flute piece Busby had written for his friend, Michael Parloff, who would soon become the principal flutist at the Metropolitan Opera.

Every evening after finishing a day’s shoot on a film, Altman would host a little soiree, gathering together the editors, actors, and crew to smoke grass, drink, and jabber. Peter Boyle would drop in, and Lily Tomlin and Elliott Gould. In the middle of all this entertainment and drinking and smoking grass, Altman asked the group to listen to some music. Busby’s tape was there, along with the tapes of two other composers.

Altman had his engineer play each of the three tapes while he used a stopwatch to time how much silence lapsed before anybody spoke. The person who had the longest silence would win. “Even if they said: ‘This is wonderful,’ they’d stopped listening because they were talking,” explains Busby, who heard the story later. What Altman wanted was a visceral response. He wanted to see how engaged the listeners were. “It was very Zen,” says Busby, “and mine had the longest period of silence.”

Meanwhile, to help pay the bills, Busby had a weekly cooking gig at a trendy New York diner called Ruskay’s (located at 75th and Columbus, for those who remember New York in the 1970s).

One day, while in the prep kitchen peeling carrots and potatoes, the phone rang. It was Robert Altman. “I like your music,” he said. “Have you ever written a film score?” “No,” Busby replied, while looking down at his shoes. Everything he had peeled that day, was on them. “Have you orchestrated one?” “No” again. “I said no to every question. And he said, ‘Well, can you?’ I said, “Yes.” He said, ‘Okay, the job’s yours.’”

What an amazing shot in the dark! Et voilà. Busby was whisked off to a state-of-the-art recording studio in Burbank, California.

Every day he would sit for about three hours, watching the film and getting its images and their flow in his mind. Each reel was twelve minutes long. So when they would finally set a reel he had already been thinking about it, or feeling it. Altman invited the film composer John Williams to come in to watch. Williams had done two scores for Altman, “Images” and “The Long Goodbye.” He watched the dailies, turned to Busby, and advised him, “When you see water, write some music.”

And there was water everywhere, from the opening scene in the geriatric center to Janice Rule’s murals of reptilian, scaly-limbed creatures writhing on the bottom of swimming pools.

Williams also assembled the orchestra, bringing together wonderful musicians who could quickly read modern music. Altman agreed to let Busby bring Michael Parloff to work with him. Busby recalls: “ I remember walking out into the studio in Burbank, this very fancy recording studio with all these really encrusted, wonderful musicians who had played all kinds of film scores, and I announced: ‘I’m delighted to be here, gentlemen. I have to tell you, I’m not a conductor.” And their faces kind of looked like: ‘What are we in for?’ I said, ‘I brought along my friend, Michael Parloff, because he plays my music perfectly. He’ll show you exactly how it should be played.’”

Of course, Busby did set tempi and did more or less conduct, but he really turned it over to the performers. ‘This is chamber music,” he told them, “I want you to think of it that way. Just listen to each other and play it like you were by yourselves.’” And they did. Miraculously, it all worked and fit flawlessly with the picture.

When the film was released, Altman turned to Busby and said: “It’s so perfect, I don’t know how to talk about it.” And neither do I. Listen to it here.