Brandeis Plunders Its Rose Art Museum

The Rose Was a Rose Was a Rose

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 01, 2009

A conflagration of shock, anger and protest erupted when in a front page story in the Boston Globe it was announced that Brandeis University President, Jehuda Reinharz, through an unanimous decision of the Board of Trustees, decided to close the renowned Rose Art Museum and sell its unique collection of modern and contemporary art. NY Times Editorial

The building, which was designed by Harrison and Abramovitz 48 years ago, and added to most recently with the Lois Foster Wing designed by Graham Gund, is slated to be reconfigured as a fine arts study center with studio and exhibition space for undergraduates and faculty.

The current Rose director, Michael Rush, an authority on video art, was not informed of the fate of the museum until the decision was announced. The overseers of the museum, its members, and numerous donors were also kept in the dark. Recently, Rush had commissioned an evaluation of the collection of 7000 plus works. A net worth of $350 million has been reported. Its actual value in today's ravaged art market may be half that estimate. Rush has stated that he undertook the appraisal as a tool to convince the university of the significance of the collection and its need for support. A further expansion had been considered to provide space for the display of works from the permanent collection. The $5 million Lois Foster wing was a gift in her name from her late husband, Henry Foster, who died in 2008. Dr. Foster earned his degree at the Middlesex College of Veterinary Medicine which preceded Brandeis on its Waltham campus. He chaired the Board of Trustees from 1979-1985.

When Rush decided to evaluate the worth of the collection he has commented that he was advised by friends not to let the university have access to that information. In hindsight that concern was well founded. The collection, an asset of the university, has proven to be far too tempting as a means of saving it from a drastic downscale including reduction of faculty, programming, and its core mission as an institution for teaching and research. Ironically, Rush and the Rose staff, whose jobs will be terminated at the end of June, are in the midst of editing a catalog of the collection which will go ahead with publication in September. Instead of a celebration and document as originally intended it will serve as a marketing tool for the sale of works When that happens there will be no curators on site to handle the inventory. Brandeis will have to hire scabs for this task.

At its peak the endowment of the university, which was founded in 1948 on the campus of the former Middlesex College of Medicine, was some $712 million. In the current recession, that has been reduced by 23%. It is ironic that the worth of the Rose collection, estimated at $350 million, represents about half of that former figure. As a relatively young institution Brandeis does not have the deep pockets of the leading colleges and universities. It has consistently used its resources and fund raising for expansion of a now densely crowded campus. This entails enormous debt which by law is served through the interest from the endowment, reserve, and emergency funds that appear to be tapped out. An operating deficit of $10 million has been reported but appears to be more severe and is projected to escalate sharply as the overall economic recovery is expected to last for several years.

Before making the drastic and unethical decision to close the Rose and sell its collection, there were apparently desperate pleas to the usual sources of Jewish philanthropy. Ironically this is precisely the group of individuals and foundations that were the most prominent victims of the multi-billion dollar Ponzi scheme and fraud of financier Bernard Madoff. Impact on Jewish philanthropy In a time when the Dow has fallen from a peak of 14,000 to some 8,000, because of the Madoff scandal, the Jewish philanthropic community has been clobbered. With funding sources greatly diminished, Reinharz and the Board have acted rashly. It has made a Solomon decision or "Sophie's Choice" by squandering its cultural heritage, smearing forever its moral and ethical reputation, betraying all those who donated works of art to the Rose, and casting a dark shadow over any future support from alumni and friends.

It is ironic that in taking this action, Brandeis University, a paradigm of radical liberal education, has set a precedent that may spread to other hard pressed institutions. Imagine, for example, that Phillips Academy in Andover decided to close its Addison Gallery of American Art and sell its collection. The cultural loss would be beyond comprehension. One of the arguments against the Rose is that it attracts only about 14,000 visitors a year and little or none of its collection is on view. Similarly, the annual attendance of the Addison Gallery is relatively small as it is for virtually all such institutions. Before its move to the Boston waterfront, the annual attendance of the Institute of Contemporary Art averaged just 20,000. The audience for modern and contemporary art has always been marginal. But college and university galleries have played an enormous role by exposing students to the fine arts and creating future generations of artists, curators, art historians, critics, collectors, and appreciators.

As an alumnus of Brandeis University, class of 1963, the loss of the Rose is a devastating and personal betrayal. During the dedication of the Rose, on May 3, 1961, as the president of the student art club, I was one of the speakers. In the student newspaper, The Justice, I took on founding director Sam Hunter for not involving the students more directly in the Rose and its programming. In June, through the Poses Institute, Hunter held a remarkable symposium which was a who's who of the avant-garde art world of the time. The speakers were housed in the vacant dorms. Because I lived in Brookline, I was one of the few students to benefit from the event. I took Sam to task for that and other excesses. His Larry Rivers opening, in which the artist performed with his jazz combo, was legendary. The entire New York art world showed up. My sculpture professor, Peter Grippe, introduced me as "a young artist" to Hans Hoffman who asked me if I was a "painter or a sculptor." The current and last Rose exhibition is devoted to Hoffman's work. He was one of the most influential artists and teachers of his generation. Interestingly, since the announcement of the closing of the Rose, the Boston Globe reports that its attendance has spiked.

Having been turned down by the Ivy League colleges that I applied to there was an emergency meeting with my family. I hastily applied to and was accepted by Boston University and Boston College but they didn't interest me. My mother mentioned that her former school, The Middlesex College of Medicine and Surgery, was now Brandeis University. She suggested we drive out to Waltham and take a look. The admissions director was C. Ruggles Smith, the son of the founder of Middlesex, John Hall Smith. C. Ruggles had been her English teacher. They greeted each other warmly, and while they caught up, I was asked to take a look at the campus. I liked what I saw, and that afternoon, was accepted. The impact of that decision is beyond calculation.

My mother, Dr. Josephine R. Flynn, often told of her colorful days as a student at Middlesex. Smith, during the depression, hired gangs of day laborers using on site stone materials, to construct fantasy buildings like "The Castle." She recalled the thrill during a winter semester when "the heat came on." Over many years of struggle with the American Medical Association (AMA), the school was never accredited. She recalled Smith as a brilliant surgeon and visionary. When he sold the school, its charter and campus to the founders of Brandeis in 1948, for one dollar, she recalled him stating that having been mistreated by the AMA and government officials over the years "now they will have to deal with the Jewish people." The founding of Brandeis University was so tenuous that its first dorms, the Ridgeway complex, were designed so that, in the event of failure, they could be converted to apartments.

During my freshman orientation, there was a panel discussion by several faculty. They were brilliant and contentious. Coming from the traditional and conservative Boston Latin School, I had never been exposed to anything like that. Over time, I came to appreciate being a part of the most brilliant and radical student body and faculty in America. Martin Peretz was the president of the student government. Abbie Hofmann was a senior when I was a freshman. His future wife, Sheila, was president of the art club. They sent me a birth announcement. I hung out in the cafeteria and had coffee with Evan Stark and Angela Davis. My chemistry lab partner (I flunked ending my pursuit of Pre-Med thank God) later blew up a bank in New York as part of the Weathermen, a radical underground group. We attended rallies and marches. Brandeis students were on the freedom buses that integrated lunch counters in the South. They were involved in voter registration drives, and black student leaders were invited to Brandeis to hone their skills.

As a young and growing university Brandeis was able to attract an astonishing faculty because many were black balled by other universities during the era of McCarthyism. Some, like the philosopher Herbert Marcuse, had spent time in jail. Angela Davis was a protégé of Marcuse. We were taught by Irving Howe, Philip Rahv, Paul Radin, Cyrus Gordon, Abraham Maslow and attended the lectures of Max Lerner as well as the Sunday afternoon PBS broadcasts of Eleanor Roosevelt. I studied the Humanities with Howe's wonderful wife Thalia. And art history with the mystic Leo Bronstein. During the spring semester there is an annual Bronstein Day in his memory. My greatest mentor was the art historian Creighton Gilbert. Before my time, Leonard Bernstein taught in the music department. We attended regular performances of chamber music, much of it contemporary and avant-garde. The music department was chaired by Irving Fine and included composers Harold Shapiro and Alvin Lucier as well as the cellist Madeline Foley. In dorm rooms we listened to Cage, Stockhausen, and Mingus. The arts were important at Brandeis and I became a part of a legacy that now seems trashed and defiled. In the numerous e-mails of the past few days there have been comments about the indifference and hostility to the arts by the current administration.

Brandeis is notorious for having spawned radicals and revolutionaries. On September 23, 1970, its alumni Katherine Ann Powers and Susan Saxe, were involved in a bank robbery in Brighton, Mass. in which the police officer Walter Schroeder was killed. They had been radicalized by a former Walpole inmate, William Gilday, Jr., a career criminal, who was studying at Brandeis. For a time, about half of the FBI most wanted list was comprised of Brandeis grads.

While political and social advocacy is the most obvious aspect of the Brandeis heritage, a radical, avant-garde sensibility pervaded all aspects of its education including the arts. The founding and legacy of the Rose Art Museum reflects that tradition. That's why this seems like cutting off the head to save the body.

To begin with, the museum was poorly designed and ill conceived. It was intended as a kind of jewel box for the precious objects, a collection of ceramics, of its donors, Edward and Bertha Rose. As a museum, the original Rose of Harrison and Abramovitz was a disaster. As you enter the space it is dominated by a central staircase that descends to a lower level further exacerbated by an absurd reflecting pool. The impediments of staircase and pool, while adding a decorative element, make it impossible to step back from a large work of art, or to install freestanding sculpture. Initially, these sight lines were further obstructed by glass cases surrounding the stairs in which were installed examples of porcelain. It took many years for them to be tactfully removed.

Sam Hunter had a different vision for the Rose. He came to the museum as one of the foremost experts on Modern and Contemporary Art. The text book "Modern Art," one of 40 that he has published, was co authored with architectural historian, John Jacobus, whom I knew from visits to Dartmouth College. It is the standard in the field. Starting from scratch, Sam decided to form a permanent collection. He was given seed money from the Gevirtz-Mnuchin families.

With $50,000, he purchased 28 works of art. Prior to the founding of the Rose there were important modern works scattered around the campus. I worked for Linda Marks who was head of exhibitions for the Goldfarb Library and helped to install works in buildings and offices. We also installed traveling exhibitions circulated by the American Federation of Arts (AFA). I recall uncrating Rauschenberg's 1955-58 "Odalisk" which is now in the Ludwig Museum in Cologne. It brought back memories to see it there. At one point Marc Chagall was supposed to paint a mural in the library. He visited the campus, but it never happened. During an opening, I was a guard for a collection of African art which Jacques Lipchitz screamed at me were "fakes."

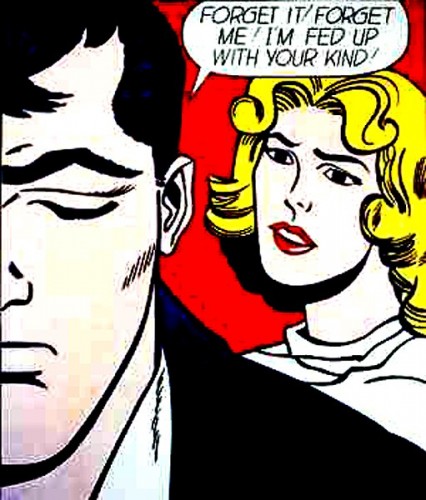

Instead of putting the Gevirtz-Mnuchin fund into the acquisition of one or two works by established contemporary artists, Hunter opted to invest in emerging artists. I recall being shocked and amazed when the collection was first shown. Among the highlights were works by Lichtenstein, Johns, Rauschenberg, Warhol, Oldenburg, Rosenquist, Louis, Marisol, Wesselman, Dine, Kelly and Gottlieb.

Years later during an interview with then director, Carl Belz, he pulled out the file and showed me the acquisition forms. The most expensive work was the Johns at five thousand dollars. The cheapest, an Oldenburg "TV Dinner," for a few hundred. By that time, the annual acquisition fund for the Rose was about the same amount as that initial purchase by Hunter. Belz was collecting drawings by sculptors like Richard Serra and David Smith. During that interview, he estimated the net work of the Gevirtz-Mnuchin collection at some $17 million. Today, that may represent the value of single pieces from that collection. If they go on the block the Johns, Raushenberg, and Lichtenstein works will have estimates in that range.

These and other works in the Rose collection are frequently borrowed for museum exhibitions. I was proud to see them included in the Guggenheim retrospectives for Lichtenstein and Rauschenberg, a Met exhibition of Rauschenberg "Combines," and MoMA's Warhol retrospective.

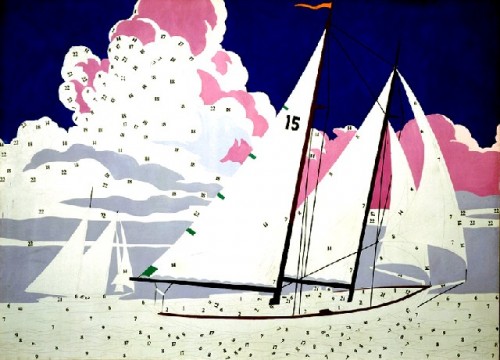

Over the years there were deaccessions which never seems to be a good idea. During a visit to a German museum I encountered the Warhol "Do It Yourself-Sailboat" 1962. This early "hand made" Warhol a spoof of a paint by numbers view of a yacht was swapped for a later silk screen "Saturday Disaster" 1964. A rare early deKooning "Woman" was exchanged for a larger later painting. Similarly, the Boston Red Sox traded Babe Ruth to the Yankees because the owner at the time put the money into backing a forgettable musical called "No No Nanette." What about this sounds familiar?

The tragedy of selling off the Rose Collection is that once it is dispersed it looses critical mass and historical context. It was a disaster, for example, that the collection of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas was sold by the heirs of Stein. Today we have only vintage photographs to remind us of their vision. More fortunately, the collection of their friends Etta and Claribel Cone survives intact. When they returned from Paris they gave their collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art. While Stein focused on Picasso the sisters Cone concentrated on Matisse. Ironically, the greatest work in the Cone Collection, the 1907 Matisse "Blue Nude," was initially owned by Gertrude Stein. It was loaned to the 1913 Armory Show by her brother Leo Stein (at first they collected jointly). When the Stein/ Tolkas collection was sold "Blue Nude" was bought by John Quinn who later sold it to the sisters Cone. The Picasso 1905-1906 "Portrait of Gertrude Stein" it was acquired by Alfred Stieglitz who donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While it is significant that these important works from the Stein/ Toklas collection ended up in major collections this pales by comparison to the value, context, and significance had the collection remained intact.

It is the integrity and critical mass of a collection that attracts other donations and acquisitions. Significantly, 80% of the works in the collection were donated. The importance of the Rose was magnified by the stupidity and apathy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston which did not create a department of contemporary art and a policy to collect until 1971. Today its collection is mediocre by comparison to that of the Rose. Only since moving to its new building has the Institute of Contemporary Art decided to form a permanent collection. It would appear to be a moral imperative for Brandeis to donate or loan some of the key Rose works to the MFA and ICA. In the past few days Reinharz has backed away from a quick fire sale. There will be court battles by estates and donors and everyone knows that this is a terrible time to sell works of art. Perhaps this is an opportunity to make long term loans of the Rose collection to the MFA and ICA. Currently the MFA and Harvard University Art Museums are under construction but when these projects are completed in the next couple of years these would be appropriate venues to display the Rose collection if the university dismantles the museum (its stated intention) but decides either not to sell or to do so over an extended period of time.

After the initial splash of the Hunter years the museum has had an uneven history. Hunter was followed in 1965 by the late William Seitz a scholar and curator of equal reputation. I vividly recall a luncheon interview with Seitz and the visiting artist Frank Stella. Seitz had been his professor at Princeton. The artist mumbled and jiggled his false teeth while Seitz for the most part answered the questions. After lunch I attended the studio class by Stella during which he said little or nothing to the students. I wrote an article for Boston After Dark (now the Boston Phoenix) with the headline "Stella Means Star in Italian." During the Belz years I interviewed Helen Frankenthaler when she showed at the Rose. It was similarly unmemorable and enervating.

When Carl Belz followed Seitz the Rose had fallen on hard times. The Saxe and Powers incident impacted fund raising for Brandeis. The Jewish community preferred to give their money to Israel, hospitals, and other charities. Belz had been teaching art history when he was offered the job at the Rose. There was little or no money for exhibitions and catalogues. He began to work closely with Boston artists with an annual exhibition surveying their work. Belz was also open to acquiring work by local artists including myself. He included me in a show of work by alumni artists. I also gave works to the Rose from my own collection of Boston artists. Like many alumni I had always thought that one day I would bequeath works of art and archival materials to my alma mater. Once the Rose closes it is unlikely that I will ever set foot on the campus or give a dime to Brandeis.

As a critic, over the years, I have had an intimate relationship with the Rose writing numerous reviews, interviews and feature articles. It was always a pleasure to visit. Often I would interrupt Belz during an afternoon nap or his favorite soap opera. To be sure there was a laid back feeling for Team Rose as he put it. The curator, Susan Stoops, is now curator of contemporary art for the Worcester Art Museum. When not installing work the artist/ preparatory, Roger Kizik, created hand crafted frames for paintings. His frame for an early Marsden Hartley painting, is as much a work of art as the painting itself. I was such a consistent supporter of the Rose that the former ICA director, David Ross, stated to me that "If Carl Belz spit in a bucket you would write a story about it."

After a rough beginning Belz and the Rose got back on track. He later stated to me how grateful he was that during those hard times that the university had not raided the museum's collection. Obviously, it was just a matter of time.

Yesterday I had a phone conversation with my colleague from Art New England and former boss, Daniel Ranalli, the director of the arts administration program for Metropolitan College at Boston University. I taught Modern Art (using Hunter's text) and a seminar on the avant-garde for Dan. "What was great about the Rose is that when they showed my work" Dan recalled "and that of other Boston artists, it was always in the context of works from the collection and other artists with national reputations. I thought my work held up and it had great meaning for me to show at the Rose. The show was curated by Susan Stoops and included several large photo installation pieces. I was willing to sell work at a reduced price just to be in that collection. Many of the donors are complaining but at least they got tax write-offs. As an artist selling or donating work to a museum you don't get that tax break."

Just what will now happen with estates, individuals, artists and foundations who donated works to the Rose? A case in point is the Herbert W. Plimpton Collection of Realist Art. I have been in contact with the private art dealer, Sunne Savage, who advised and worked with Plimpton. When he passed away it was a major acquisition during the tenure of Belz. It includes an important nude self portrait by William Beckman of the artist and his former wife. What will now be the fate of those seminal works? One donates to museum collections with the expectation that your gifts will be seen and appreciated by future generations.

The individual most hurt and dismayed by these events is Lois Foster. She and her late husband were greatly committed to the Rose. According to news reports some years ago Henry Foster apparently talked the President and Board out of a decision to sell off the Rose collection. Instead the Fosters decided to renew their commitment to the museum. When that decision was made Lois Foster, who chaired the overseers and friends of the Rose, ousted Belz. There was an outcry from the Boston arts community. Joe Ketner was brought in with a mandate to work with Foster on fund raising that resulted in a new wing. The result, unfortunately, was an undistinguished big box designed by Graham Gund. Part of that development might have included a renovation of the absurd Harrison and Abramovitz interior and a less awkward transition to the Foster wing. There was discussion of a next phase of development with a wing for the permanent collection.

Ketner left but after a hiatus has returned to Boston to teach and curate for Emerson College. It will be interesting to see how that develops. The current, and last director, is Michael Rush, a former Jesuit priest and expert on video art. His shows have been lively and insightful. The last one I saw was an Alexis Rockman exhibition. It was up in spring 2008 while Rockman had a large work in the "Badlands" exhibition at Mass MoCA. The more I see of Rockman's work the less I like it.

But that was always the fun and challenge of the Rose and its exhibitions. The museum functioned as a laboratory for radical issues and ideas in contemporary art. Even if one didn't agree or appreciate what was shown you were better for the experience. With the imminent closing of the Rose, and the possible sale and Diaspora of its collection, a big chunk of my heart and soul is lost forever. This is a sad time for the arts in America. And it ain't over.

Links to Other Articles

David Bonetti Class of '69 Saint Louis Post Dispatch

Palm Beach Daily News Impact on Donors

NY Times Roberta Smith

Donations Decline

Should we care about the arts?

Hard times for New York art galleries

Arts as part of stimulus package

List of Massachusetts Madoff Clients

Brandeis University President Apologizes for Mishandling of Museum Closing

Museum professionals and alumni appeal to reverse Rose decision