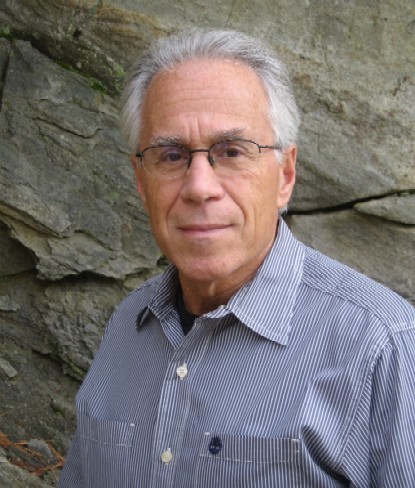

Steve Nelson on The Boston Tea Party

Reelin' and Rockin' (Part 1)

By: Steve Nelson and Charles Giuliano - Jan 24, 2011

Charles Giuliano: For the past several years, you’ve been involved with an effort to establish the Music Museum of New England. Bring us up to speed on how that got started and who are some of the people behind this effort.

Steve Nelson: The MMONE story really goes back about eight years, with an earlier effort to start what was called the Boston Rock & Roll Museum. That was essentially a virtual museum, with a lot of information about different bands on a website. Then in the spring of 2003 they did a couple of benefit shows at the Regent Theatre in Arlington, MA.

One was billed as “Live at the Surf” in honor of the three Surf Ballrooms which a guy named Bill Spence ran on the South Shore in the Sixties, which were popular teenage dance halls. That show was hosted by the legendary Boston DJ Arnie “Woo Woo” Ginsburg and featured another local music legend, The Remains, a Boston band who played The Ed Sullivan Show, opened for The Beatles on their last U.S. tour in 1966, and still do the occasional reunion gig.

Also on the bill was another Boston-area group who regularly played the Surfs, a kind of British-invasion cover band called The Mods, who opened for The Rolling Stones in 1966 at the Manning Bowl in Lynn. That was an infamous gig in which it rained during the Stones set and the kids rushed the stage. The cops, fearing they had a riot on their hands, set off tear gas and shut the show down.

Anyway, the R&R Museum also did a “Live at The Rat” show, with several performers who played at that notorious punk club near Fenway Park, like Willie “Loco” Alexander, Real Kids, DMZ and Unnatural Axe. They also hoped to do other shows, including “Live at the Tea Party,” which is where I came in. I was asked to become a member of the Museum’s advisory board, because I was the manager of the Boston Tea Party rock and blues club in 1967 and ’68.

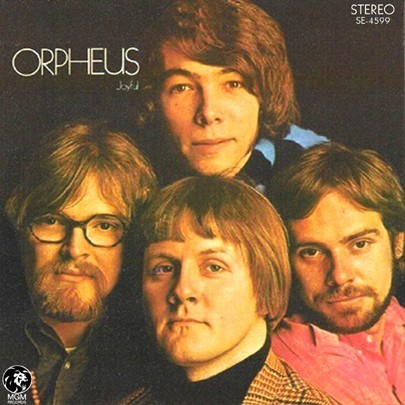

One of the other advisory board members was Harry Sandler, who was the drummer for The Mods but went on to play with Orpheus, a Sixties Boston band who put out four LPs and opened shows for the likes of The Who and, if you can believe it, Janis Joplin at Tanglewood in 1969.

Another member was Mike Fondo, a lawyer and accountant for Fidelity who had no professional connection to the music scene other than being a fan who read about the Museum in the Boston Globe and volunteered to help. It’s always good to have a lawyer and accountant on your side. Also on the board was Gary Sohmers, who you may know from “Antiques Roadshow” on PBS. He’s the pop culture appraiser with the white ponytail and Hawaiian shirts.

As it turned out, the Boston Rock & Roll Museum went kaput for various reasons, but after it folded Harry, Mike, Gary and I got together for dinner every couple of months. And out of those meetings came the idea to start another museum, only it would cover all genres of music, not just rock ‘n’ roll, and all of New England, not just Boston. Mike got us set up as a “tax-deductible charitable organization,” so we could accept donations, and we were off and running. Gary’s no longer actively involved, but Harry, Mike and I are the Board of Directors for MMONE.

Since then we’ve been joined by Dave LaCamera, who has many years experience in artist management and booking bands and speakers. We also created an Advisory Council which includes among other people the concert producer Don Law, who took over as manager of the Tea Party when I left, and Wayne Ulaky, who played bass for The Beacon Street Union, another Sixties Boston band. Wayne went on to help run his family business, Canobie Lake Park, which over the years had presented an amazing range of performers, from Duke Ellington to Sonny and Cher.

CG: Until now MMONE has primarily been a website, although you do have a project of putting plaques on historic places like the original site of the Tea Party, the club I mean, not the Revolutionary War event, in the South End of Boston.

SN: Yeah, that’s been our plan, to first build a comprehensive website about the artists, the venues, the media, the producers and everyone else who’s been part of making music in New England. The web obviously makes all that available everywhere, not just to visitors to a bricks-and-mortar museum, which is our ultimate goal, by the way.

We’ve got a good start on the site, plus a Facebook page, but it’s a work in progress, and we’re fortunate to have some dedicated volunteers helping us with it. We’re all driven by the same passion, “to preserve, honor and showcase New England’s musical heritage,” to quote our mission statement.

It’s funny, back in the early Seventies, after the Tea Party had closed, Harry and I used to get together and kvetch about the lack of opportunities for local bands to play and learn their craft before a live audience, and to get exposure, as they say in the music biz. Of course, since then, many great clubs have come and gone, and New England has produced many great musicians.

But here we are, forty years later, Harry and me, still wanting to see New England’s talent get the recognition we think it deserves. And by the way, as far as the Museum goes, we’re talking about artists who were professionally active in New England at least 15 years ago, which is our criterion for inclusion on the site. The younger kids are on their own, or at least until they’ve put in their 15 years.

As far as the plaque you mentioned, that project actually got started before MMONE. When the Boston Rock & Roll Museum contacted me about helping with “Live at the Tea Party,” which never happened by the way, I decided to check out the Tea Party online. I figured most people had long since forgotten about it, but I was astounded to find that it had truly become a legend.

And with good reason, when you consider the bands who played there. Led Zeppelin on their first US tour in January ‘69. They only had an hour’s worth of material, but the crowd wouldn’t let them stop, so they just kept jamming. John Paul Jones called this the key gig in the transformation of the band’s performance style to the long sets they became noted for, with extended solos.

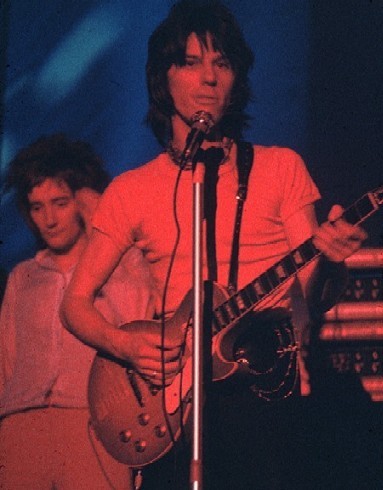

Also on their first U.S. tour in June ’68, The Jeff Beck Group with Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood, who were basically unknown at the time. Blues giants like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and B.B. King. Van Morrison when he first moved to Cambridge from Belfast and was developing the material for his classic album Astral Weeks.

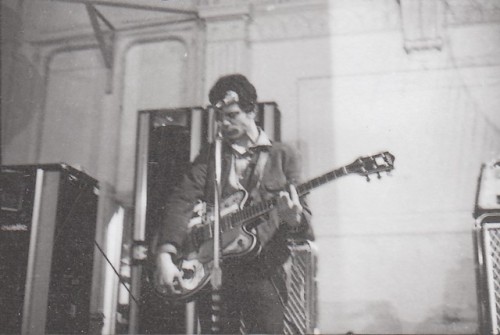

My personal favorite was The Velvet Underground. The Tea Party was essentially their home club from ‘67 to ’70, a period when they did not play in New York. People came up from the City to see the Velvets, and on stage at the Tea Party Lou Reed called it their favorite place to play.

And of course there were the aspiring local musicians who went to the Tea Party to see those bands, like Jonathan Richman before there were The Modern Lovers and several members of Aerosmith before there was an Aerosmith. And many locals who played there, most notably Peter Wolf, who fronted The Hallucinations and then The J. Geils Band.

Well, back to the plaque. Around the time I got involved with the Rock & Roll Museum, I found out about a program run by the Bostonian Society to put markers on historic buildings. That’s Boston’s historical society, they’re the keepers of the old State House, and nothing’s more historic than that around here. The marker program was about a hundred years old, but after doing a lot of the really old architectural stuff, the Bulfinch buildings and the like, they expanded their focus to include sites of more recent social and cultural significance.

So I approached them as to whether they’d consider the original site of the Tea Party, which was in an old 19th century building on the corner of Berkeley and Appleton Street in Boston’s South End. They said well, submit an application and we’ll consider it. So as part of that application, I went to the Registry of Deeds in Boston to trace the origins of the building.

It had a big Star of David window on the third floor, so we had always assumed it was an old synagogue. But it turns out to have been a Unitarian meeting house built in 1872-73. The land for the building was donated by a wealthy Boston businessman named John Gardner, who developed much of the South End after it was filled in, like Back Bay was. His son Jack married a prominent socialite you’ve heard of, Isabella Stewart.

CG: The Isabella Stewart Gardner of Boston museum fame?

SN: The very one. So we not only had a legendary rock club, but the connection to an important family in Boston’s business and cultural history. And I also found out that the meeting house was dedicated to the memory of Theodore Parker (1810-1860), a controversial reformist Unitarian minister with ties to Emerson, Thoreau and the Transcendentalists. Parker was an outspoken abolitionist and early advocate for women’s suffrage.

In a speech in 1858 he said that “Democracy is direct self-government over all the people, by all the people, for all the people,” which was echoed by Lincoln in his Gettysburg address. He also talked about how the curve of history “bends toward justice,” as Martin Luther King later said.

Of course, the kind of people who hung out at the Tea Party in the Sixties were for civil rights and women’s rights and against the Vietnam War, so Theodore Parker’s spirit was very much alive at the Tea Party. What karma!

CG: So if the Tea Party building had been a Unitarian meeting house, what about the Star of David?

SN: I’m not sure, but the Bostonian Society thinks it’s probably got to do with the Unitarians honoring other religions when they put up the building. The South End was a center of early Jewish settlement in Boston at that time, and a few years after the building was contructed Hebrew Sunday School classes were held in the basement. But for sure it was not built as a synagogue.

In the 1930s for a while it was the Calvary Temple, and arcing over the back of the stage of the Tea Party in big letters was “Praise Ye the Lord.” Just before the Tea Party came in it was briefly a folk coffeehouse called the Moondial, which I don’t know much about. But Dave Wilson, the publisher of Broadside whom you interviewed recently about the Boston-Cambridge folk scene in the ‘50s and ‘60s, probably knows something about it.

Anyhow, with all that going for the building, I did get approval from the Bostonian Society for the marker. And by that time we had launched MMONE, so as an organization we held an event unveiling the marker and commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Tea Party’s opening night, which was January 20, 1967.

It was a great event, with Don Law, Willie Alexander, who played opening night with his first band The Lost, and lots of other people from the music scene. We videotaped the presentations and interviewed a lot of the people there, who shared some fascinating stories about the Tea Party and what it meant to them.

Links

Music Museum Of New England website

Music Museum Of New England Facebook page

The Boston Tea Party Facebook page

The Velvet Underground Web Pages

Video from the Tea Party marker event