Philippe de Montebello: Museums Why Should We Care

Resigning Met Director Reveals Stress of Returning Antiquities

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 24, 2008

During a lecture last night at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts "Museums Why Should We Care" Philippe de Montebello, who is retiring as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, showed slides of the newly renovated Greek and Roman galleries. Their recent reopening is widely regarded as capping off a remarkable 30 year tenure, the longest in the history of the museum. The Met has almost doubled its exhibition space and he has presided over a staff of more than a thousand, "personally appointed" its current 110 curators, and supervised more than 700 special exhibitions many of which are described as "blockbusters."

Having achieved so much his departure should be a time of honors and celebration. As the Cincinnatus of our greatest American museum it should be a moment to return to the ancestral estate and tend its vineyards. But he leaves under a cloud of controversy, not of his own making, when he recently presided over the protracted and difficult negotiations which resulted in the return of one of the Met's greatest treasures, acquired during the tenure of his flamboyant predecessor, Thomas Hoving. The Archaic Greek, Euphronios Krater, and some 20 other antiquities, were claimed to have been stolen from Italy. In return, Italian authorities are loaning three works of similar period and style. But they clearly are not equal to the greatest masterpiece of ancient Greek pottery. For the museum, and the legacy of de Montebello, it is clearly a devastating personal loss which, until now, he has declined to comment on publicly.

While projecting the slide of one of the galleries displaying the Met's collection of some 3,000 Greek pots he commented with the wit that punctuated an insightful lecture "They are not all stolen." During opening remarks Michael Conforti, director of the Clark, briefly alluded to de Montebello's strong views of the trend in which there are ever more frequent law suits to reclaim "stolen" property. Conforti remarked that while discussing demands for the British Museum to return its controversial Elgin Marbles to Greece, de Montebello commented to him that Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum, would not be able to "resign for some time." Implying, not on MacGregor's watch, and that he is a relatively young man. In other words, not to anticipate that Great Britain will give back the Elgin Marbles any time soon. It also implied that de Montebello's resignation is connected to the controversy of returning the "stolen" antiquities to Italy.

This was not how de Montebello explained his decision to retire when asked about it by the New York Times. De Montebello stated that "After three decades, to stay further would be to skirt decency. This has not been an easy decision- it's wrenching for me, it's been my entire life. But it's time." During a phone interview with the Times a reporter pressed for de Montebello's personal response to returning 21 antiquities to Italy. The article revealed that the interview ended abruptly because of a bad cell phone connection.

During the Clark lecture de Montebello often stressed that visitors should take the time to seek out and carefully study individual objects. He conceded that the array of Greek pots is daunting in its sameness. That they are similar in color and shape but that as a measure of their importance the pots take up "valuable real estate and are housed in expensive vitrines." He showed a few examples including an Etruscan vase with animals and a Greek amphora with its famous image of a woman playing a harp.

After the lecture I approached de Montebello and Conforti. I pointed out that the slide he showed of the gallery of Greek pottery displayed the Euphronios pot which is no longer there. He seemed surprised by that and turned to Conforti for confirmation. He then stated that he will have to get a new slide of the gallery for future lectures.

Having raised the issue I asked for his personal response to returning the treasures to Italy. There was a long pause. His hands were buried in the deep pockets of an impeccable, double breasted, pin striped suit. It seemed to be a characteristic gesture of leaning back and away from confrontation; to shroud himself in the protective uniform of patrician authority. He is described in the media as a very private person despite a high profile and public position.

I reminded him that there was a glitch on the cell phone when a Times reporter asked this question. But that at the moment there was no such misfunction. "No I did not answer" de Montebello said seemingly gathering his emotions and taking a long breath when faced with such a difficult question. Seizing an opening Conforti informed de Montebello that "Charles is a journalist." It implied a warning that an answer to the question would be on the record.

"When I returned from Italy after negotiating the return of the antiquities" he said with startling candor "I was in bed with shingles for six weeks."

Pressing on I characterized the past year with its triumphs including the reopening of the Greek and Roman galleries as a time of celebration for a great career. I asked how the loss of the Euphronios Krater impacted that legacy? There was poignant body language, a shifting and regrouping of the persona, that revealed the devastating strain of those negotiations. I asked if the stress led directly to his decision to resign. Again, he was remarkably frank in stating that it was "A factor, one of many factors."

By then, there were others surrounding us as he patiently answered questions. Another reporter asked if he had advice for his successor? De Montebello stated that he received no advice from his predecessor (Thomas Hoving) and would offer none to his successor.

The opportunity for an intimate and emotional exchange with de Montebello was a highlight of an extraordinary evening. The capacity audience was enthralled when he discussed the power of art in our individual lives and just what comprises a masterpiece. Often his discussions of works, many in the collection of the Met, were stunning in their insight and poetic nuances. De Montebello also surprised and amused the audience with his acerbic, autocratic humor. He derided the marketing of museums as "great places to dine and, oh yes, also look at art." He discussed the trend of popularizing the museum experience as demeaning its primary purpose of becoming intimate with great objects. But he also revealed faith in the "Great Unwashed," an expression that shocked the audience (unheard of in Posh Williamstown), and their ability to seek out the best works.

He was later asked if the admission price of $20 discouraged the "great unwashed" from visiting the Met. He responded that it represented a "voluntary payment" and that visitors, unlike at MoMA, may enter free of charge if they so choose. Once inside the Met there are no further fees including entry to special exhibitions. Another question asked whether "dining," which he had dismissed as a part of the marketing of the museum, wasn't an important part of funding. Again, de Montebello responded in a tart and surprising manner and dismissed the notion of the museum restaurants as money making ventures. "I can raise more money during five minutes at a dinner party than the restaurants earn in a year," he stated.

There was a touch of autocratic pique that flavored his lecture and answers to probing questions. As F. Scott Fitzgerald famously commented "The very rich are different from you and me." And de Montebello is a French aristocrat born into title and privilege. But he is also a deeply passionate advocate and populist determined to share a commitment to our cultural heritage. He emphasized that great masterpieces are created by "The Human Species."

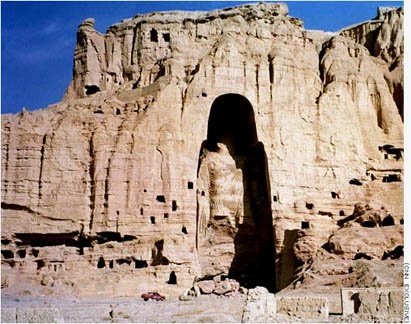

His lecture started with how great a loss occurred when the Taliban, in Afghanistan, during March of 2001, despite the pleading of the world, dynamited two ancient Buddhist sculptures carved into the sides of mountains. It characterized fanatical iconoclasm in the guise of fundamentalism. He showed dramatic before and after images of this destruction. This was followed by a discussion of the looting of the museum in Baghdad during the period of "Shock and Awe" when we invaded Iraq and failed to protect treasures which de Montebello described as belong to all of us. He described such acts as sawing off a branch of the tree of knowledge.

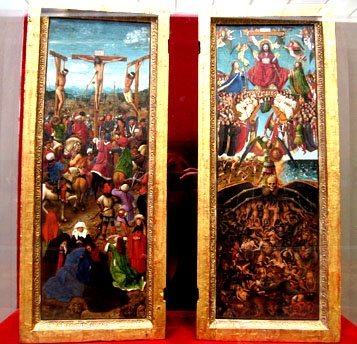

When visiting museums he urged the audience to seek out less famous objects. He projected a vitrine with a group of Ancient Egyptian objects. He focused on how artists used chips of stone to practice drawing. That these are the kind of works that are buried in a museum which houses endless galleries filled with treasures. He lingered long, and in great detail, over the Hubert and or Jan van Eyck, 1420-25, Flemish diptych "The Crucifixion and The Last Judgment." Focusing on the left panel, while noting its tiny scale (22 ¼ by 7 ¾"), he discussed a number of details stressing how easily such a small work is overlooked by most visitors.

He took enormous pride in discussing the process of persuading the Met's Trustees, none of whom are experts in fine arts, to approve the $45 million acquisition of a Duccio (ca. 1255-1260 to ca. 1318-1319) masterpiece "Madonna and Child." It was the only Duccio available and the Met had no example by the Siennese master. During negotiation of its acquisition the museum learned that it was competing with the Louvre which also had no work by Duccio. De Montebello took pride in discussing what may indeed be his greatest acquisition as representing the transition from the Byzantine tradition to the naturalism that would characterize the development of Renaissance style.

Last night, de Montebello was never more riveting than when he discussed works of art. He allowed us to experience Jean Antoine Watteau's "Mezzetin" (1718) with fresh insight. He described the melancholy of the serenade as the musician thrust back his head singing plaintively to an unseen listener. He discussed a detail of straining fingers pressing the frets of the guitar. And how the mood was enhanced by a female statue in the garden seemingly shunning the musician.

He offered pairs of example with similar elements- the ripples in the garment of a Buddha compared to those in the robes of a French, Romanesque Madonna and Child- to underscore similarities that bridge cultures separated by centuries and geography. In other comparisons he paired works of similar period and style revealing how a Flemish portrait by Hugo conveys more power and passion than a more reserved treatment by Memling. He contrasted the compelling use of artificial light in a French, Baroque painting of Magdalene, by de la Tour, with the play of natural light over objects in a work by the Dutch, Baroque artist, Vermeer. He discussed how the great "Return from the Hunt" by Bruegel, in Vienna, is riveting while another Flemish painting of a winter scene by van Valckenborch in the same museum scarcely deserves our attention.

For this lecture de Montebello arrived at 5:30 and immediately returned to New York. We caught up with Michael Conforti just after he had seen off his distinguished visitor. In a discussion of the many changes that are now redefining the mandates of museums, particularly the morality of their collections, Conforti commented that de Montebello is committed to write and lecture on the subject. Rather than step away from the fray he intends to be active in the debate. There is a politically correct agenda that the museums of the world give back their treasures to the nations of origin. Just where do museums draw the line and preserve their collections?

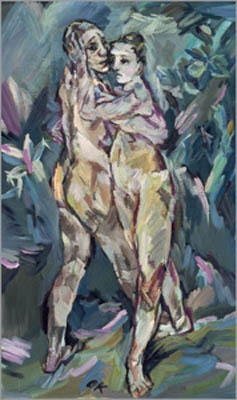

I suggested to Conforti that the great European museums acquired through conquest and Imperialism. In that sense, American museums are comparatively pure and untainted. Conforti responded that "if you dig deep enough" no museum collection is beyond scrutiny. Indeed, today's Boston Globe includes a report that Claudia Seger-Thomschitz of Austria is demanding the return by the Museum of Fine Arts of one of its few modern masterpieces "Two Nudes," 1913, by Oskar Kokoschka. The seminal expressionist painting, a self portrait of the artist dancing with Alma Mahler, was allegedly sold "Under duress by Oskar Reichel, a physician who ran an art gallery in Vienna during the Nazi occupation of Austria." The Globe reported that the MFA has recently filed a suit in federal court to retain ownership of the painting.

Given a climate in which such claims and law suits are routinely reported in the media can anyone doubt why de Montebello has chosen to step away from this constant stress and strain? He may now serve in an even greater role as one of the primary contributors to the debate surrounding the definition and future of museums. As a private citizen de Montebello will be free to express what he cannot as director of the Met. Until now, museums have been where to display what nations steal. But how will we define museums when and if they have to give it all back?