Carrie Mae Weems at Nashville's Frist Center

Three Decades of Photographs and Video

By: Edward Rubin - Jan 23, 2013

This country is just too fucked up about color. It’s a distraction. People at each other’s throats just because they are a different color. It’s the height of insanity, and it will hold any nation back - or any neighborhood back or anything back. Blacks know that some whites didn’t want to give up slavery – that if they had their way, they would still be under the yoke. And they can’t pretend they don’t know that. If you got a slave, master or Klan in your blood, blacks can sense that. That stuff lingers to this day. Just like Jews can sense Nazi blood and Serbs can sense Croatian Blood. It’s doubtful that America’s ever going to get rid of that stigmatization. It’s a country founded on the backs of slaves. ~ Excerpt from a Bob Dylan Interview - Rolling Stone Magazine, September 27, 2012

The Frist Center For The Visual Arts, also known as “The Little Museum That Could” has been mounting important, ground-breaking exhibitions since it opened its doors twelve years ago in Nashville, Tennessee. Housed in an Art Deco post office from the early ‘30s, the building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Frist is Nashville’s answer, on a smaller scale of course, to “big boy” museums like the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It may be small but it mounts big. It’s most recent exhibition, a stellar one at that, was Fairy Tales, Monsters, and the Genetic Imagination. Organized by Frist’s ingenious Chief Curator Mark Scala. It traveled throughout Canada.

Following in Scala’s inventive footsteps, not an easy thing to do, is the Carrie Mae Weems’ retrospective, Three Decades of Photographs and Video (September 12, 2012-January 13, 2012). It is beautifully curated by Kathryn Delmez who wrote her thesis on the African American artist. This provocative, thought-provoking, and timely exhibition – think Spielberg’s Lincoln, Tarantino’s Django Unchained, both currently up for Oscars – and Obama in the White House – will be on the road throughout 2013 and well into 2014.

After leaving the Frist, its originating venue, it travels to the Portland, Oregon Art Museum, (February 2-May 19, 2013), Cleveland’s Museum of Art (June 30-September 29, 2013, Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University in California (October 16, 2013 – January 5, 2014), ending its run at the Guggenheim in New York City (January 24-April 23, 2014).

Carrie Mae Weems, whose subjects are examined from every conceivable angle, are race, gender, class, identity, culture, history and institutional power, She focuses on what it means to be a human being, past and present. Weems has been exhibiting, here and abroad, solo and in group shows, for over three decades. Still, her work and reputation, like the lives of most African Americans, a fact her body of work aims to change, has been flying mostly under the radar.

“It’s fair to say that black folks,” she told one interviewer, “operate under a cloud of invisibility—this too is part of my work, is indeed central to the work…Even in the midst of the great social changes we’ve experienced just in the last years with the election of Barack Obama, for the most part African Americans and our lives remain invisible.”

Viewed in this light, is her retrospective something of a corrective—an early marker, pointing the way to a post-racial era?

To use an overworked term, the paring of Weems’s with curator Delmez is a marriage made in heaven. I am not talking about the team’s visual canniness – a given in this case – but the exhibition’s imaginative layout which turns the visitor’s viewing experience, in gallery after gallery, into a poignant walk through the artist’s own personal history, the history of African-Americans in this country, and by extension, peoples around the world.

Preparing us for the journey is Family Pictures and Stories (1978-84), the artist’s first major photographic series. Here Weems generously shares, through candid images with text, and actual audio recordings, the outer and inner lives of her large Portland, Oregon based family. One particular picture, Family Reunion, depicts her family at what appears to be the beginnings of a picnic.

“No matter what I am doing I’m always trying to figure out how to have a conversation with myself around the materials and ideas that are deeply troubling for me and things that keep me up at night and get me up in the morning,” Weems confided during her opening talk at the Frist. “What are we? What are we doing together? How do we negotiate and make it through this complicated maze of life that we are involved in. This is the only question that I really have. And this is the thing that I come back to again, and again, and again, and again, and again, but through a different door, through a slightly different angle.”

As the exhibition demonstrates, Weems, ever looking for answers, has been traveling around the world ever since she was handed a camera by a friend in 1974.

One asks where has Weems gone since then? The answer seems be just about everywhere and she is still traveling.

In her Sea Island Series (1991-92) we find her documenting the black Gullah communities of coastal South Carolina and Georgia whose semi-isolation fostered the survival of many African customs and beliefs. In her Slave Coast and Africa Series (both 1993) Weems navigates the cities of Ghana, Senegal, and Mali; studying the ‘architecture of slavery’ – slave holding facilities included – of the once important centers along the slave trade route.

For Dreaming of Cuba (2002), wearing a long flowing dress, a signature used by the artist in numerous series, she focused on the hard life – sometimes placing herself in the picture - of Cuba’s, ‘everyday’ men and women at home and at work.

With Roaming (2006), a stark photographic essay, Weems, flirting openly with the dramatic, plays Beatrice to our Dante. Donning a long black dress, and always with her back turned, she leads us through the labyrinths of Rome where we find ourselves standing before grandiose monuments and intimidating “buildings of power” pondering history and our place in it.

The Museum Series (2007-present), still playing the muse, we stand, face to façade, with Weems before the world’s great museums. She is thinking about artists, black, women, and others of the disenfranchised whose work has been marginalized within the art world establishment. It is a subject she first touched on in her provocative series Not Manet’s Type (1997) which critiques how white male “masters in the canon” define female beauty through their paintings. Here, scantily clad, and in one photo lying nude across a bed, Weems offers herself as a would-be artist’s model. The first work in this narrative series reads “It was clear, I was not Manet’s type Picasso—who had a way with women only used me & Duchamp never even considered me.”

Much of Weems’ work is deliberately crafted to expose the underlying racism in mainstream culture. In Ain’t Jokin (1987-1988), a series of staged photographs with text, the artist pairs Afro American individuals with hot button visuals, like a man holding a watermelon and a woman with a fried chicken drumstick. One photograph, illustrating a racist joke that has been around for a long time, brought a knowing smile to my face thus proving her point? Here, an attractive black woman – as the joke goes it was Diana Ross, or any other famous black woman – is seen looking into a mirror while a white faced woman stares back at her. The text reads, “Looking Into The Mirror, The Black Woman Asked, “Mirror Mirror On The Wall, Who’s The Finest Of Them All? The Mirror Says, “Snow White, You Black Bitch, And Don’t You Forget It!!!” Had these works and words come from the hand of a so-called white person – as they do give strength to negative stereotypes – it would be considered inflammatory, especially by today’s, bound, tied, and politically correct adherents.

Though photography has long been Weems’ mainstay, she is equally adept in presenting her “educational lessons” in video, as well as installation. In Afro-Chic (2009), filmed in luscious color at a modern day fashion show, the artist playfully revisits the ‘60s when the phrase Black is Beautiful held sway, and Afro hairstyles, among blacks and whites alike were all the rage. In the background of the video, adding a touch of political history, hangs a picture of Angela Davis during her radical activist days, sporting, like all of the models jauntily treading the runway, her own iconic, trend-setting afro.

In Ritual and Revolution (1998) – one of the three installations on view – the viewer, rubbing shoulders with history, is made to walk through low hanging diaphanous muslin banners, each bearing an historical image where struggles for equality, such as the Palace of Versailles, and the Hermitage, took place. In the background, filling the air with sound and thought is Weems sonorously reciting the history of various battles for freedom lost and won.

From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995-96) – a powerful indictment of man’s inhumanity to man – is Weems’ most painful and guilt-conjuring series. Using early daguerreotypes of African slaves from which she has re-photographed, enlarged, and tinted a bloody red suggests lives taken and blood spilled. She goes in for the kill.

By adding denigrating bold-faced phrases to each individual image, suchlike “Others said ‘only thing a niggah could do was shine my shoes”, “you became playmate to the patriarch”, and “an anthropological debate”, words that define, as well as distance the black man from the white man’s world, she is mirroring the intent of the original photographers.

As Weems stated in her talk “I was trying to bring together the history of photography on the one hand, and the history of blacks in photography on the other, or at least the history of the representation of blacks through American photography.”

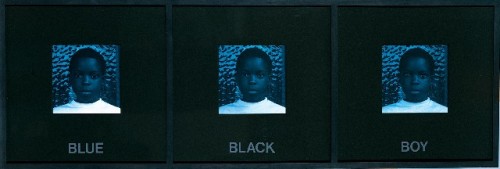

In Colored People (1989-90), an edition of hand-tinted photographs of young children, the artist celebrates the diversity of skin color – the many shades of black - among African Americans. Simultaneously she points out the existence of a color-based caste system within African American communities and society as a whole. Comprised mainly of triptychs consisting of three repeated images, each portrait with its own color and identifying one word title is a comment on the artificiality of such limiting and meaningless labels.

Reading from left to right, one sets reads “Moody, Blue, Girl”, another “Blue, Black, Boy”, a third, “Golden, Yella, Girl.” In Slow Fade To Black (2010-11), a series of barely discernable images of famous African American female performers from Josephine Baker, to Marion Anderson, to Nina Simone, all purposely presented out of focus, Weems laments their fading presence in our collective memory.

The pièce de résistance, the perfect place and way to end the exhibition which is exactly what I did, is at the feet of Kitchen Table Talk (1990), unarguably Weems’ most startlingly beautiful, if not important, work to date. Accorded a gallery of its own, the series, a set of twenty cinematically brilliant photographs and fourteen stand-alone text panels tells the story of a modern black woman.

The writing, highly reminiscent of Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives (1909) in its honest, and straight- forward simplicity, tells the story, with Weems playing the central role of a woman in search of her self. Filmed around a dramatically lit kitchen table, it features her male partner, assorted children, and her girlfriends. It begins with Weems, as Everywoman, talking about needing a man, and ends with the artist sitting alone at the table playing solitaire.

Through trials and tribulations, as she tells it, the artist, in what I suspect are scenes taken from her own life, has become independent, self-reliant, and strong within herself. A God-given gift that the artist wants us to know is within the reach of all of us.