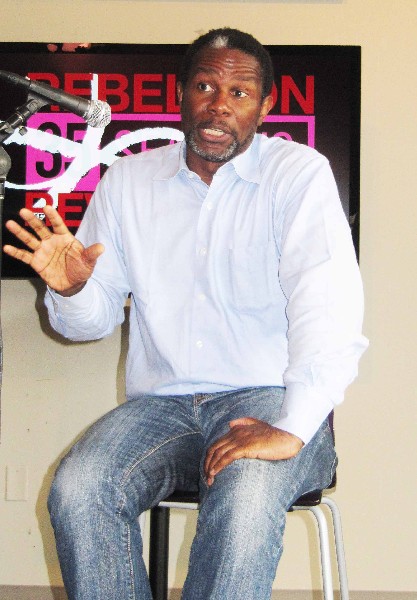

John Douglas Thompson Three

Portraying Louis Armstrong and Joe Glaser

By: John Douglas Thompson and Charles Giuliano - Jan 22, 2012

Charles Giuliano Louis Armstrong was the genius of his generation. More than any of his peers he solidified what came before and defined the paradigm of jazz for the 1920s. By the end of that decade there was a shift from the ensembles of New Orleans to the big bands of Chicago and New York nightclubs. After the Hot Five and Seven recordings he often fronted the bands of other musicians with numerous recordings which I have listened to from 1932 and 1933. The arrangements were often uneven although his solos and vocals were outstanding. He put together a band which toured in the U.S. and broke up while in Europe. All that effort came to nothing resulting in Armstrong firing his manager and hibernating in Paris for several months in 1934. That’s when he connected with Lou Glaser as his manager. They had known each other in Chicago. From 1935 until his death Glaser remained his manager. You can hear a significant difference in the big band recordings before and after Glaser. In 1935 Armstrong was back in the studio recording a mix of material with Glaser suggesting tin pan alley tunes, including “La Cucaracha.” Glaser also had a lot to say about hiring and firing musicians. It was Glaser who promoted Armstrong as a celebrity and put him on the path to commercial success.

After WWII big bands were out of fashion with the emergence of bop. Only Duke Ellington and Count Basie prevailed but with great difficulty. After some retooling Armstrong emerged as a part of the Dixieland revival and toured the world in the 1950s through the Department of State with the All Stars. It was a return to his ensemble style.

If you look at the jazz critics and musicians of the 1950s there was a lively debate and rift between Hot and Cool jazz. Armstrong was the leader of the traditional approach with Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis as the spokespersons for the more avant-garde progressive approach. The turf war was very real and generational. The fact that Armstrong was dismissed as a buffoon and Uncle Tom was more than just a social slur. More than that it was an artistic struggle.

There was a real shift as jazz lost its mainstream status with a black audience. You couldn’t dance to bop while Dixieland or Trad was old fashioned. The 1950s saw the emergence of rhythm and blues which eventually was appropriated as rock 'n' roll. To hold onto a black audience dance is essential from R&B to Soul then Hip Hop. As Duke put it “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.”

John Douglas Thompson I don’t agree with that. I understand that is your position but it is not how I see it. That’s your opinion but certainly not mine at all.

CG Ok but certainly by the 1950s Armstrong was primarily embraced by a conservative white audience with a taste for traditional jazz.

JDT That I agree with and there is reference to that within the context of the play (Satchmo at the Waldorf). All the blacks who used to be in the audience are now gone.

CG Ironically that’s exactly what eventually happened to Dizzy and Miles.

JDT Yeah, yeah, yeah.

CG How do you explain that?

JDT There’s aspects of that in the play and the book. There is so much about Louis that I never knew. That I’m learning bit by bit by bit as I’m talking with you now. There are things that I’m learning from the book (Terry Teachout) that I never knew or understood. Or even had the idea that these things were going on. What I find really interesting about the play is that it reveals this other side of Louis Armstrong that I never knew existed. That’s the trick and really interesting thing about the play. It reveals this other thing to an audience that thinks we already know him.

CG The challenge for you will be to move him beyond the caricature and self parody that he had willingly become.

JDT The mugging and all that stuff.

CG Right. He was indeed a consummate entertainer. Glaser was right when he told him not to split his lip trying all those high C’s. The audience doesn’t care about that. Glaser said they don’t even want to hear your trumpet. They want “Hello Dolly” and “Mack the Knife.”

JDT You’re right. He became this consummate performer. You can look at all that he did in the later years that people remember and shy away from. The mugging and all that stuff but it was still considered to be entertainment. He talks about that. He says “I’m just an entertainer and I love the audience.” Perhaps it left a bitter taste with audience members who saw him at the end of his career. This play somehow redeems that for me. It’s not as if I’m up there playing that side of Louis. We are trying to go for this other more deep, meditative side of Louis. Things that were going on for him mentally and physically and his emotional state. More so than what we saw when he was on stage. The play is purposeful in the sense that it is set in the midst of him doing a concert. For the audience he is talking to it’s when he’s in his dressing room. In that state of the play we get to know and understand him more. He’s not the entertainer in the play I don’t think. We see brief moments and flashes of what he is capable of as an entertainer. But the play is much more about who he is as a man.

CG Do you find him angry and resentful?

JDT There is certainly some anger and resentment that I’ve been uncovering. But I don’t know because it’s a long way away from even the first day of rehearsal. (Opens at Shakespeare & Company in August.) I think that’s a really interesting part of the play. If you were to just look at Louis from television and all this stuff I’ve been looking him in You Tube. You would sense that he doesn’t bear any anger or resentment. If you watch him perform everything is happy and smiling. On the flip side if you see someone like that you have to assume there is something burning deep inside. There’s anger and frustration there that he can’t let out. There is real sadness because his entertainment persona is the exact opposite of all those things. To me that’s what’s interesting about Armstrong.

CG How are you going to handle Joe Glaser?

JDT At this point I really don’t know. It will be important because the play goes from Joe to Louis and Louis to Joe. For me the challenge will be to get the cadences of Glaser’s voice. He’s a Jewish man. It will be a matter of getting the cadences of his speech down. How he talks. Then also build him. It seems as if he is very strong and aggressive. He’s got a very aggressive personality which is very different from Louis’s. I’m really trying to bring out the differences between the two of them. They’re on the page. But how I’m going to manifest that, particularly Joe, I’m not quite there yet.

CG How are you going to feel when, as Joe, you’re going to have to refer to Louis as a schwarze?

JDT It’s part of the text in the play. Right now I don’t know.

CG I understand that but it is an aspect of the very complex relationship between them. Glaser did not include Armstrong in his will because he owed money to the mob. He was in a tough spot and although he screwed Louis, in the end, you can feel sympathetic because of the tough spot he’s in. The mob owned him. That took precedence over his relationship with and loyalty to Armstrong.

JDT They had a very, very complex relationship. I’m trying to understand the complexities that are there on the page. To read them on the page and then manifest them as an actor is very difficult. That process is as complex as the relationship I’m going to try to bring together on stage. I don’t understand how Joe could call Louis, maybe not to his face, but certainly as Joe does within the context of this play, refer to Armstrong in that manner. To a man that he loves and refers to as his best friend. On the other hand that he would say something that is so derogatory about someone he loves as a best friend.

CG That’s the world we live in.

JDT Yeah. That’s fascinating to me. That’s a fascinating aspect of the play. Because it’s that relationship. That’s where all the tension is in the play. That’s where the theatricality is. It’s between Louis and Joe Glaser. And what they say about each other.

CG This is your Anna Deavere Smith moment.

JDT (Laughs) I don’t think I'm as good as Anna Deavere Smith.

CG She is so wonderful in the ability to channel the nuances of ethnic dialogues. To assume multiple characters. Is this the first time that you’ve faced that kind of challenge? On stage to switch between a black character and a Jewish character. That seems like a tough thing to take on.

JDT Oh yeah. Tell me about it. You’re preaching to the choir. This is why we do this stuff. It will be a huge challenge for me. I just hope to be successful at it. I enjoy the process of attempting the challenges. Seeing what happens. I don’t know what happens on the other side. It’s like being a diver. I’m jumping and I’m told there is water. I can’t see it. But I am told by all the people who are after me and behind me to jump that there is water. If I go off this board that there is fifteen feet of water. That I’ll be fine. Right now I’m taking my third jump off of the board and I’m in the air.

CG Haven’t you played Shylock?

JDT Yes at Shakespeare & Company. It wasn’t on the main stage. It was a student production. I was a student. They said “We’re going to do Merchant of Venice and John you’re playing Shylock.” I would like to play Shylock again. It’s a great role. I would like to get to that within the context of my classical work at some point. In the next four or five years I would love to play that role.

CG Coming back to Satchmo. You wonder is this a tribute play? Is it about nostalgia for a popular artist? Which is why bio plays and films based on popular musicians from Benny Goodman, Buddy Holly, Ray Charles, Woddy Guthrie, Leadbelly, Johnny Cash and even Ike and Tina are so often bland and disappointing. Beyond recreating the music and bio of the artist’s life, more often than not, they are disappointing. In the case of Armstrong, however, as you state there is so much that we don’t know beyond the public persona. In researching Armstrong I was surprised to learn how he spoke out against racism in Little Rock. To the point of endangering his career. That incident lends a crucial aspect of dramatic tension to the play. Without that perhaps there would be no motive for doing the Louis Armstrong story.

JDT In the context of the play Little Rock is obviously important. Just for me, John, there would be a reason to do the play beyond Little Rock. I find that episode really powerful and moving. It speaks to Louis and the kind of person he truly was. What he was trying to say and do and how he was trying to lead by example. How we wasn’t what people thought. An Uncle Tom who didn’t care about the rights and issues of the black community. That’s really strong for me. However, what’s fascinating for me was that he had this manager, Joe Glaser, and what Joe Glaser did to promote Louis to be a star. The reputation that Joe Glaser had of being a really rough tough guy. It’s just fascinating to have Louis and Joe Glaser. I just never would have put those two guys together. So that’s what’s fascinating about the play. The Little Rock incident is quite wonderful. The dialogue about “Hello Dolly” and how that came to be. How he beat out the Beatles when that song became Number One. The stuff about the women who were in his life. The love he had for his wife Lucille. The things that she did for him. The way Joe Glaser picked his musicians. The way that he let everything be handled by Joe Glaser. He just got out there and played. The stuff about the High C’s vs. singing. I didn’t know that about him. I just thought he was this incredible artist, which obviously he was, and it pretty much shaped his career. But you see through the play how much Joe Glaser shaped his career. Joe was involved with the mob and at the end of the day Joe screwed Louis. Because the mob screwed Joe. It’s a fascinating story that builds through the tension of their relationship. Louis doesn’t know why Joe Glaser fucked him over.