Touring Carnivals in Europe

Part Two: Nice, Tenerife, Binche, Aalst, Viareggio

By: Zeren Earls - Jan 10, 2013

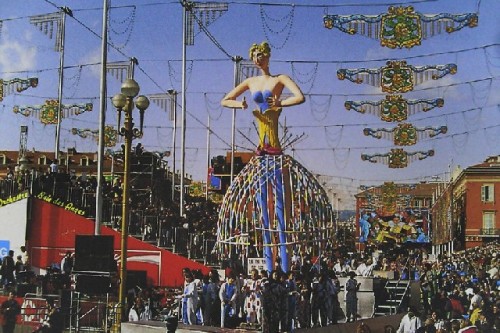

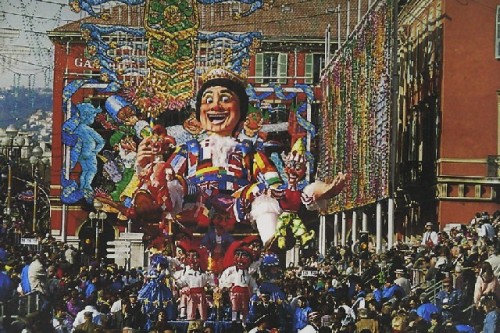

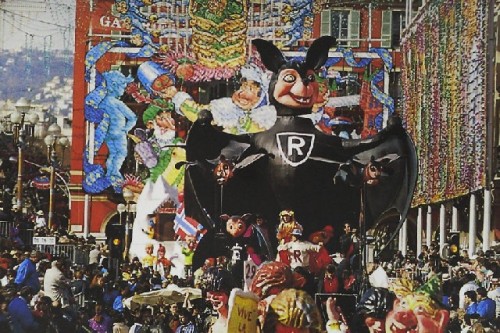

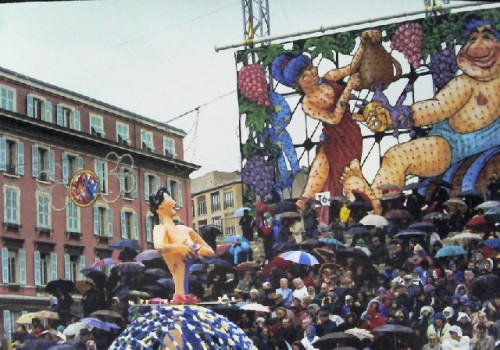

After a break of seven years, I resumed my carnival adventures in 1993 by traveling to Nice, France. The Nice carnival, on the French Riviera, is a lavish tourist-oriented show. Artists spend months conceiving, constructing, and animating fanciful floats, which people view from behind barricades along the route of the Corso (parade) or from stands by paying admission. The giant, grotesque monsters that awe and fascinate the crowds in the stands are a marvel of ingenuity and creative imagination. The main figure of the celebration is “His Majesty Carnival,” a giant paper mache king.

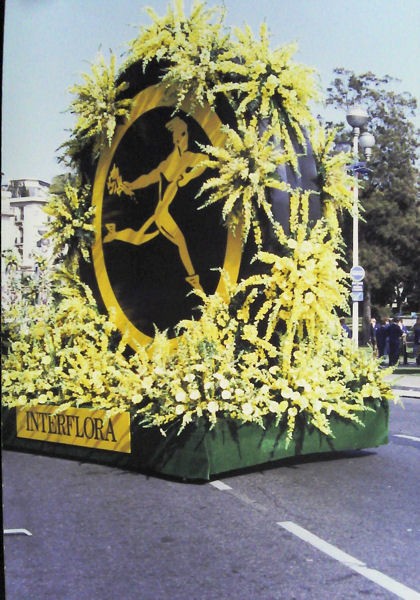

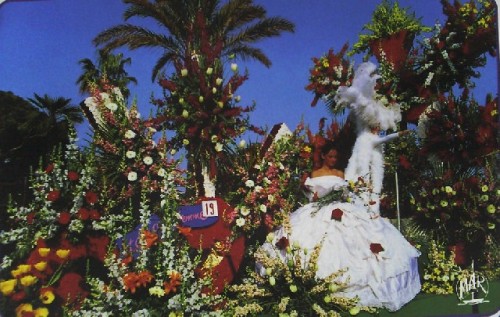

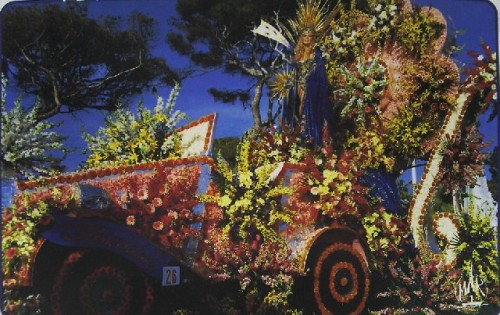

The renowned Bataille des Fleurs, or Battle of Flowers, is a grand seafront parade of beautiful floats luxuriantly decorated with cut flowers. Beautiful women dressed in elegant gowns or as bathing beauties toss bouquets of flowers to the admiring crowds. An illuminated night version of the parade features the women in revealing cabaret-style costumes. Afterwards, sophisticated spectators attend veglioni, or masquerade balls, in formal evening wear at fashionable hotels nearby. On the eve of festive Mardi Gras, following the burning of “His Majesty Carnival,” the celebration culminates in a spectacular fireworks display.

In 1995 Spain’s Canary Islands beckoned with their carnival in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The festivities started on Friday with an opening parade of all participating groups, featuring the carnival queen and her bridesmaids on floats. An impressive component of the day was the afternoon children’s parade, where large groups of young people were fancifully dressed as everything from ducks to squirrels and carried colorful umbrellas. They paraded for hours through the city streets among throngs of admirers.

Carnival Saturday was dedicated to dancing, which reached its height during the night with thousands dancing to the music of comparsas — bands playing conga music — into the early hours. The grand finale took place on Tuesday with the participation of all the carnival groups, floats, decorated cars, and the carnival queen. Evening parties continued night after night, with adult revelers in skimpy costumes of boa feathers and sequins, until Ash Wednesday, when the streets were draped for mourning.

On Ash Wednesday, people celebrate the entierro de la sardine, or “burial of the sardine.” A giant sardine made of paper mache is carried in a funeral procession, followed by wailing widows. The Catholic Church is mocked, with participants dressed as the Pope, bishops, and nuns giving blessings. When the funeral procession reaches the shore, the sardine is set on fire and its ashes blown out to sea.

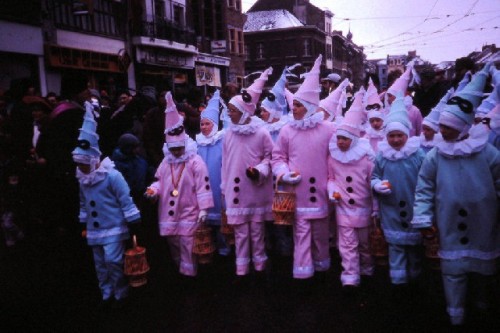

In 1996 my son Selim relocated to Brussels, Belgium, giving me the opportunity to experience two unique Belgian carnivals, in the towns of Binche and Aalst. Binche is a small town with a medieval wall around its market square in the heart of the French-speaking province of Hainaut. Its authentic carnival is fiercely loyal to tradition. The population identifies with the Gille, the central figure of the carnival. His outfit, made of linen, is emblazoned with red and yellow heraldic lions encircled with stars and bears a simple coat of arms on the back. The Gille wears a cap and a waxed mask with green glasses, whiskers and moustache in the style of Napoleon. For a few hours during the day, he wears a tall plumed hat with ostrich feathers. His ritual gestures include the carrying of cow-bells and a stick broom, and offering oranges out of special baskets.

At 4 am on Shrove Tuesday, a drummer goes to fetch the first Gille at his house. Accompanied by friends and relatives, they go from house to house to fetch the other members of the society. The small group grows as it heads to the center of town for camaraderie. Later on, they do a ring-dance of honor in front of the Gothic town hall — a highlight of the day for the Gilles and the spectators. The sight of these masked Gilles moving as an anonymous mass is unforgettable.

After lunch break, at around 3 pm, they gather again to form a procession. The 900 Gilles in their plumed hats, carrying baskets of oranges, are accompanied by imagined societies composed exclusively of people from Binche — clowns, harlequins, Dalmatians, farmers, sailors, and the like. This is followed by a shower of oranges and another ring-dance at the large central square. The carnival closes with fireworks, but the non-stop dancing, accompanied by the rhythm of the drum and the clogs, continues with gravity and dignity till late in the night. True to traditional ritual, dancers chase disease, famine, misery, and all bad things away from the community.

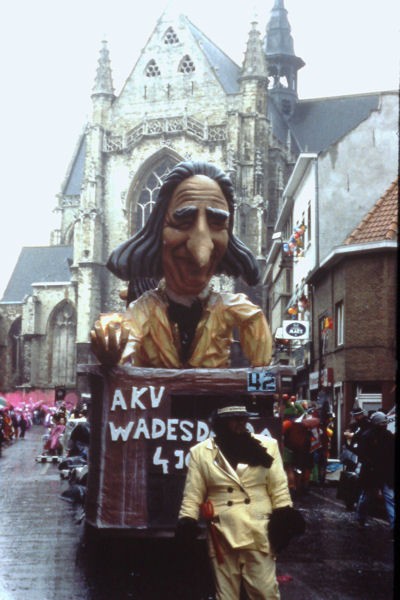

Aalst is a town of 250,000 people in the Flemish-speaking part of Belgium. It is a commercial and industrial center on the traffic route between Ostend and Brussels. The celebration of Shrove Tuesday is based on an old tradition recorded in authentic historical documents. On the Sunday before Ash Wednesday a feast, called Carnaval, opens with a unique parade. A large number of groups, all from Aalst, give their personal humorous view of outstanding events from the past year. The king and queen are represented by giant puppets, worn by a person inside.

On Monday the “onion throw” and “boom dance” of the Gilles of Aalst excite the crowd, followed by a second parade. Tuesday is the day of the “Vuil Jeannette” street carnival. Shrove Tuesday evening “burns” to cheerful music and a ring-dance by torchlight.

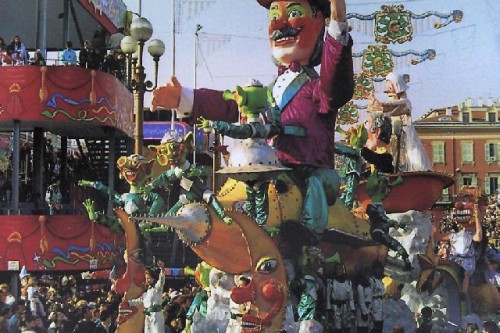

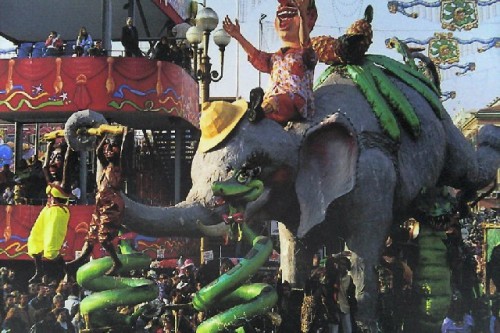

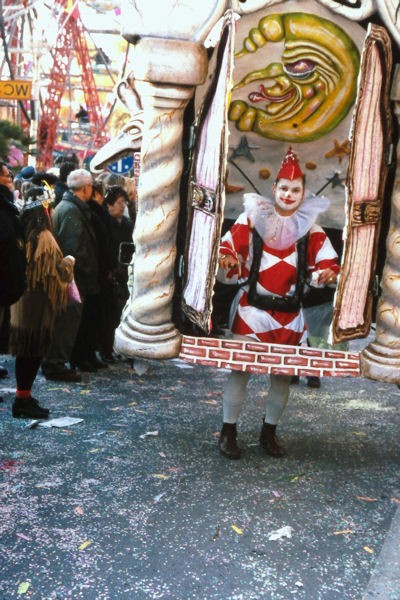

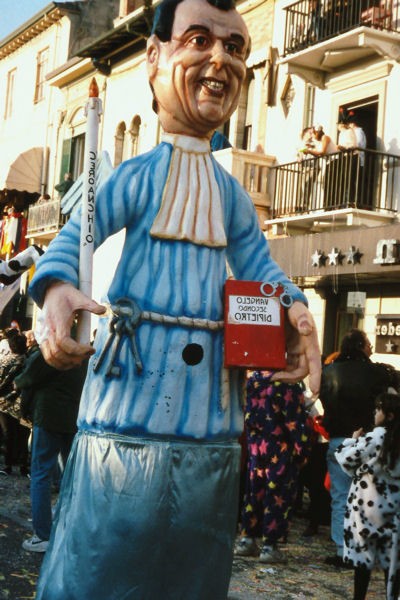

My last carnival trip was in 1997 to Viareggio, Italy, on the Tuscan Riviera, where carnival is a seafront show of colossal proportions. The class antagonism between the relatively poor port and the fashionable beach resort lends vitality to this carnival, inherited from the Roman Saturnalia tradition of poking fun at authority. The artists who create Tuscany’s famed marble sculptures are the Maghi, or magicians, responsible for the mammoth paper-mache figures on 30– to– 60– foot– high floats for the grand Corso on Martedì Grasso. Nothing escapes their biting satire. Thousands come to see who the Maghi have chosen to mercilessly caricature and what scandal is the latest target of their acid humor. Crowds dance the Tarantella, drinking and singing in the streets.

During the weeks leading up to the big event, neighborhoods take turns hosting their own street carnivals. The community spirit is alive and animated, echoing the spirit of one of the carnival floats – Carpe Diem, or “Seize the Day.”

My carnival adventures have contributed to my love of travel, which has continued since retirement. Annually I travel to a country unfamiliar to me, especially during the month of February, to get a break from Boston winters. Since February happens to be the month for carnivals, occasionally I encounter pre-Lenten festivals on route. Such was the case in Ecuador, where I became a target of revelers, who bathed me with shaving cream while taking pictures.