The Dishwasher Dialogue, In the Red Darkness I Fainted

The Almost Bearable Lightness of Being

By: Greg Ligbht and Rafael Mahdavi - Jan 09, 2026

The Dishwasher Dialogue, In the Red Darkness I Fainted

The Almost Bearable Lightness of Being

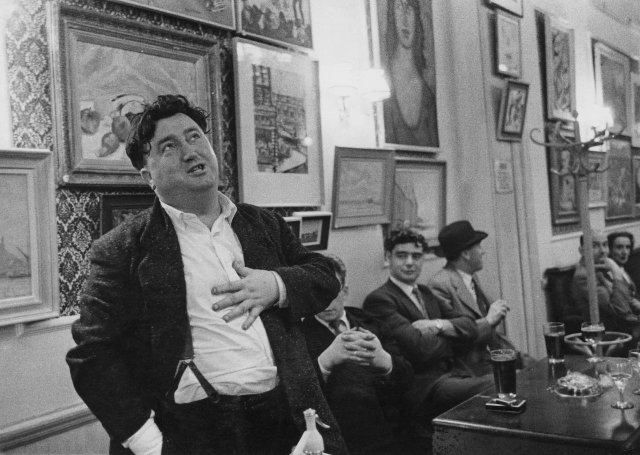

Rafael: Alongside Chez Haynes, in addition to books and stories, there was much getting out of our minds too, with sundry drugs.

Greg: As we just described in some detail. It sounds like you are suggesting a second instalment.

Rafael: Why not?

Greg: It will undoubtedly take us somewhere totally different.

Rafael: Nothing like getting stoned, standing on the back platform of a bus going along the Seine, and lighting up a joint. Later these bus platforms were deemed too dangerous. What a loss. Bouncing along, careening to the left and right when the bus turned, and of course you could talk to the girls, somehow bouncing back and forth on that back platform made talking and flirting so natural. Bumping into a beautiful woman about to light up her Gauloise by the railing, and I’d whip out my Zippo. Remember those?

Greg: I didn’t smoke but I remember Zippos and the Gauloise. Not as clearly as I remember the girls swishing by on the bus, though.

Rafael: Next thing you know we hop off by the Rue Bonaparte, have a beer. And it turns out she’s studying philosophy. In Spain you say the road from the dance floor to the bedroom is mighty long, well, from un peu de philosophie it’s mighty short.

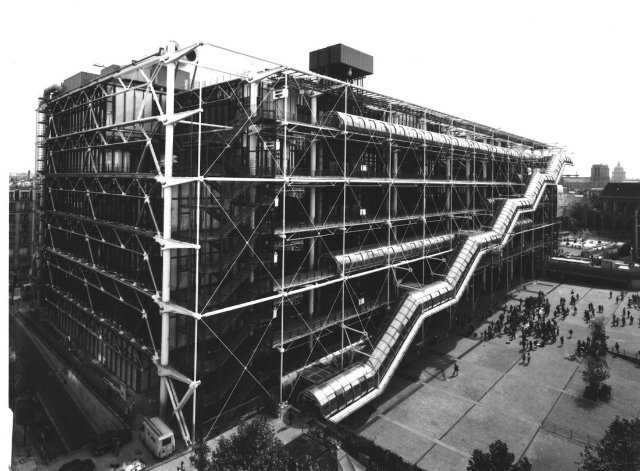

Greg: Especially in Paris. More so when facilitated with a joint. In retrospect weed facilitated that whole time more than we cared to admit. Dangled the secret of something before us. Insight? Folly? Both? I can’t say our best work flowed from our late-night experiments with words and smoke. Many a morning spent pouring through nonsense looking for those bon mots that had us rolling over in laughter the night before. But I do think many of our best times flowed from that finely rolled miniature paper baguette. Man Ray should have painted it as well. Maybe he did? Blue, Red, Green, Rainbow? Would Pompidou, its skeleton, and innards all inside out, have accepted it?

Rafael: There was whisky too. That was available, and it was legal. I told Leroy whenever I borrowed a bottle, only once in a while, from his stock in the cave.

Greg: But did you replace it?

Rafael: Sure, I did.

Greg: He never replaced the booze on the mirrored shelf behind the bar. When he drank, we refilled the whisky bottles. It was the first task of the evening. But I interrupted you.

Rafael: You know all this. Why not get it out in the open, here? It was not the case so much during the Chez Haynes years, but afterwards. And then it got worse. I suffered from depression for years. So, I drank. I told myself it was self-medication. Lame excuse, I know.

Greg: That was not you back then. But I know, later, for a while it became the worst of times.

Rafael: About five years ago, the black dogs slinked away; I don’t know why. My moods in those years were triggered by lack of money, a sense of failure in my life, but they were in the category of moods, teetering on depression. The fear of death is healthy I think; some philosophers claim that thinking about death every day is good for you, keeps the mind clear and lucid, but when the demons come in the night, well, it ain’t that easy, and somehow reaching out to God doesn’t help because I can’t get myself to believe. I just can’t pretend about that. But it’s frightening. To paraphrase Brendan Behan, being a daylight atheist is easy, being a nighttime atheist, that’s hard. So yes, I was used to getting a little down, like six feet under, beneath the asphalt, cavorting with the earthworms. Can’t get any lower than that, eh?

Greg: That’s more than ‘a little’ down. We all got down. Sometimes far down. That came with the territory. Day to day existence, frustration, self doubt. (‘What am I fucking doing here?’) The ambitions and delusions of youth. Right up there with sex, love and fame. We shared them all. But you did frequently take a step further. Added death to the mix. Although, I was never worried about you. Suicide was never a serious option. Not that I could see. But death certainly was a more visceral (fearful?) theme (preoccupation?) for you than the far-in-the-distance, philosophical concept it was for the rest of us. We were in our twenties. The end was not yet in our muscles and bones. Not viscerally anyway. But the idea was always present. It usually popped up in conversations alongside God and hell and the perils of not believing, laced with a soothing ration of wine. Or an unruly swig of whisky. Or a reckless gulp of tequila. We teased you about it—like the evening around the table in Chez Haynes. “One of us won’t be here next year”. But we were all there the next summer, and the next winter. And mostly, I think, we are all still here almost 50 years later. As, too, is death. But now with a little less patience and a broader grin. Almost a smirk.

Rafael: Death’s nag is chomping at the bit. In my small painting studio in the sixteenth arrondissment of all places, I had a bottle of Ballantine’s on the shelf. That’s middle-of-the-line blended scotch. I wasn’t going to splurge on some expensive single malt stuff. All I cared about, as I said earlier, was the alcohol content which led to the buzz I was after. And you know I kept a gun, a revolver to be exact, next to the bottle.

Greg: Drugs, Drink and Death?

Rafael: Why did I do it? Don’t ask.

Greg: I did ask. Back then I asked.

Rafael: In retrospect, it was braggadocio perhaps,

Greg: It was more interesting than that.

Rafael: I had no bullets for the weapon, but it kept the lights on in my skull. Buying bullets illegally was easy at the flea market at Montreuil. My Iranian uncle lent me the chambre de bonne to use as a studio. It was small but big enough to paint in and perhaps shoot myself. Why is there a stigma about suicide? Some people say it’s selfish and cruel to those loved ones left behind, and so on. Listen up, if you reach that stage, nobody loves you anymore, you’re sure nobody loves you, you’re just a note at the end of a shitty tune––why not?

Greg: I remember that first tiny art studio of yours well. It was a wonderful space. Hidden away along narrow corridors of countless attic rooms once reserved for the servants of the bourgeoisie. There was just enough wall and floor space to work and hang your paintings. With a large table or counter for paints and trays and brushes and a shelf left over for an empty bottle of Ballantine’s and the gun. A Colt? A Smith and Wesson?

Rafael: I have no idea. I’ve forgotten.

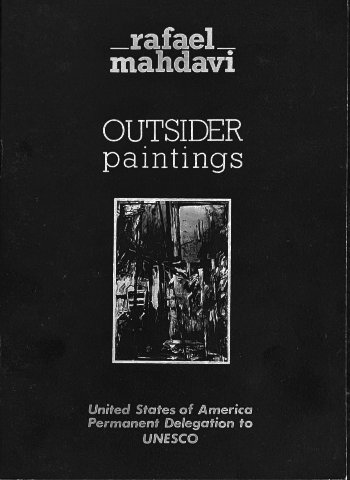

Greg: I’m afraid that’s the limit of my knowledge of guns. I don’t know if I told you but that was the space in my head when, years later, I wrote the catalogue for your UNESCO show. The Outsider Paintings?

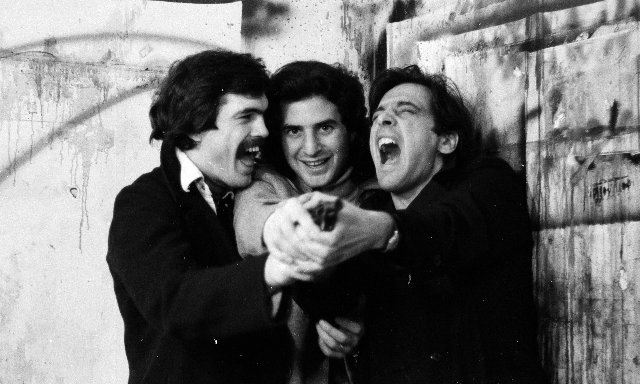

We had some great times with that gun and bottle of Ballantine’s. There is a terrific photo of you and I and our intense fellow artist friend Bentley, standing in the studio, huddled together for what must have been an early selfie. It captures his fervent eyes when he suddenly realized you were holding a gun. Admittedly unloaded. But I am not sure he knew that.

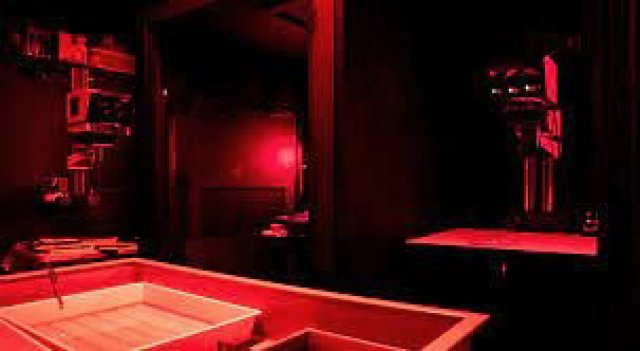

Rafael: I set up a darkroom there, remember?

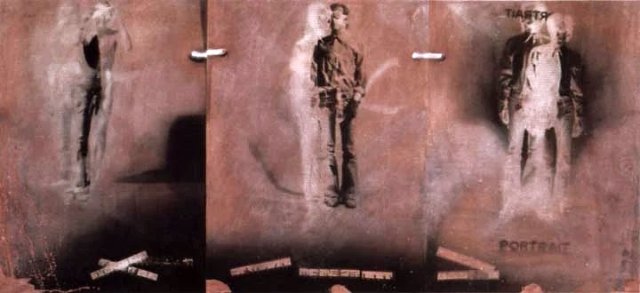

Greg: I remember you beginning your experiments using your painting tools—brushes and spray cans and developer chemicals on canvasses and materials you had previously photosensitized—to reveal photographic images of themes you were exploring in your art. I was impressed by the originality of the process and the power of the result.

Rafael: Oh, yes. I became a darkroom wizard. Bear with me here a moment. You must remember those were the days before digital photography. Taking and making photographs was complicated, and that’s why most people took their roll of negative film to a shop that developed it, and then from the contact sheet, they chose the prints they wanted. Well, I learned to do all this myself. I converted the mansard room that my uncle had put at my disposal into a darkroom. I put in a red light, which was necessary when developing and printing black and white photographs. I bought an enlarger that projected the negative 35mm film frame onto a sheet of photographic paper for a certain length of time, usually about half a minute. Next, I dipped the exposed paper into a tray with developer liquid which brought out the positive image. When the photo had emerged to my satisfaction, I slipped it into the stopper bath a few minutes, which stopped the imaged from developing any further. Finally, the paper went into the fixer bath. And finally, I washed the print. All this was for only one photo. I’ll spare you the details for larger and smaller prints, and for color photos. It was more complicated.

Greg: I was in that darkroom dozens of times. I helped on occasion. Or at least I thought I was helping. You may have just been humoring me. I do know you perfected it for many of our other projects as well as your own work.

Rafael: I wanted to do large prints, a square meter and more. I discovered a photosensitive canvas sold in Germany in rolls one meter twenty wide and ten meters long, and the canvas was developed like photographic paper. I bought a roll, built large trays for the liquids. I coated the wooden trays with swimming pool paint. I bolted the projector to the ceiling to get the distance I needed for the large-sized print I wanted. I exposed the pre-cut canvas to the light through the 35 mm negative. Since the distance from the projector to the canvas was more significant than usual, I had to expose the photo-canvas much longer––up to five minutes. I encountered my first problem when I poured the liquids into the baths, and after a few minutes in the red darkness, I fainted.

The thud to the floor jolted me back to consciousness, and I immediately realized that the chemicals’ fumes were noxious. I spent the following day installing a fan and a one-way vent in the blacked-out window.

Greg: I remember the incident. I do not remember it tempering your impulse to recklessly throw yourself into your work.

Rafael: I had ideas that could only be done by me. Hands-on stuff. I exposed the photo-canvas to my image and then instead of developing it in the bath I laid out the canvas on the floor, dipped a fat brush in the developer and painted abstractly on the canvas, thick strokes, thin ones, drips here and there and so on. And as I expected here’s what happened. Only in the areas where I had applied the developer with my brush did the image or part of the image appear. On other canvases I applied the developer on the exposed canvas with my hands and in some cases with my body.

Greg: Plainly your accident did not stop you from literally throwing yourself into your work! Do-it-yourself artistic experimentation rarely threatens life. Even flopping forward on typewriter keys late into the night can leave an impression but it is almost never fatal. Covering yourself in developer, however, may have been over testing the boundaries?

Rafael: So what? I was young, I was immortal. And this was also where we developed photographs for your plays, and where we forged your passport to get that kid out of Hungary. Remember?

Greg: I do remember. That was quite a caper. So yes, art could be life threatening. Maybe even lifesaving. Especially if you were working and writing in Eastern Europe where the ‘lightness’ of doing it yourself really was ‘unbearable’. (I only recently discovered that Milan Kundera moved to Paris around the time we did. Just saying.)

Greg: Anyway, your Faustian bet with your life began to pay off. Reputable art shows. I am thinking Galerie Stadler in Paris, here.

Rafael: Oh, yes, things started to move. I had already exhibited my work in Madrid, at Juana Mordó, and later it was the Gimpel Fils gallery in London. Solo shows followed worldwide. I didn’t make much money, but it was good for my ego. The problem was, as a painter, I was a darkroom wizard all right, but I was getting bored. I tried a few more things. But not so much in the darkroom.

Greg: I am not surprised. As stated, you bored easily.

Rafael: I bought myself another second-hand camera but with a motorized forward drive and I could take continuous pictures, by keeping the release button pressed down. One day I taped the release button down, the camera started to take photos and I threw the camera up in the air. It twirled and twirled and I could hear the camera clicking away. I made sure to catch the camera when it fell back into my hand. The pictures were every which way, up and down, sky and buildings and the street and walls and windows, and some through windows where you could see people, just imagine you catch a murder scene, and so on. A flying chance-collage. Call it in the air? Didn’t you write a play called that? Call it in the Air?

Greg: A novel. Later, in London. In hindsight, that’s what it was: ‘a flying chance-collage’. I don’t recall you making any paintings with those aerial photographs.

Rafael: No. Just experiments.

Greg: I should have insisted. I loved experiments; just to see what happened.

Rafael: I would also cover the camera lens and manually wind the slide film all the way forward. Then I would uncover the lens, start turning my body holding the camera, steadily rewinding the slide film backward manually at the same time and keeping the view finder open. This way there was no separation of the slide film into frames. Once developed I had a slide about a meter long. Some parts of the slide were blurred, others clear. I had a panoramic view of the room or the street. The problem was how to mount such a wide and thin slide. I would need to build a light box a meter wide, three centimeters high and thick enough to hold a thin fluorescent light. It was expensive and too complicated. I went back to painting on canvas with acrylic, and then later with oil.

Greg: The work that came from those experiments are some of my favorites. As are your later experiments with X-rays and Braille.

Rafael: I thought of collecting thousands of x-rays from hospitals and labs in Paris and exhibiting them on a back-lit museum floor, an x-ray carpet, and people would walk over them and look down at them. I wanted to call the show Paris Malade. A Baudelairean title if there ever was one. When I approached the Pompidou Center about this, they thought I was off my rocker. As to the Braille, my mother, who as you know was a writer, died legally blind. When I began the Braille paintings, I swear I didn’t make the connection.

Greg: I still have one of the large paintings using those techniques from your series with rags. As well as many of the large black and white photographic prints we used as posters and announcements for my plays and performances. They are a little faded as is my memory, but they still capture the time, back then, when our work suddenly felt real. And meaningful. If not, at times, a step too far.

Rafael: I don’t know if I ever told you, but back in New York I applied for a Guggenheim grant to make a half square mile photograph. Using a product called Liquid Light. On a moonless and cloudy night, I would spray liquid light from a helicopter over a square mile of Death Valley, then still from the chopper, with a stabilizer project an image, any image, it didn’t really matter, onto the desert sand for a while. The next step was spraying developer onto the desert, then stopper then fixer. Finally, I would film the resulting image on the sand as the winds in the following days erased the photo in the sand. The people at the Guggenheim politely told me I was nuts.

Greg: I am hazy on the Guggenheim grant refusal. But I do remember you describing the idea and the project. And, yes, absolutely you were nuts. And you were right to have been nuts. Remember the Hungarian Caper. That was nuts. Art, political idealism, and adventure rolled into one. We had to do something. We couldn’t just look away. And your studio-dark room experiments, (not to mention your own passport laden life) came in handy.

Rafael: We discovered that your Canadian passport picture only had an embossed stamp on it, but no color stamp. That made it easier to forge. I first carefully bleached off your photo, applied the Liquid Light mentioned above that made any paper surface light-sensitive, and then I printed the photo of our Romanian friend where your face had been. The embossment stamp, of course, remained perfect.

Greg: It sounds simple in retrospect. I wish it had been. But maybe we will save that story for later.

Rafael: Now that we’re on passports, I’ll explain why I have four passports. The Iranian passport is clear, my father’s Iranian, and after the US army drafted me and I fled to Paris, the Americans took my US passport away.

Greg: A healthy fear of death can come in handy—even if losing a passport was the price. As I was to learn as well.

Rafael: I got the U.S. passport back later after the amnesty. After my children were born in France, I applied for French citizenship, which was a Kafkaesque process. And I had a right to a Mexican passport too because I was born there. I can even apply for a Filipino passport because my mother was born there. Her parents, who were from Kansas, were visiting Zamboanga to be precise, but I never followed up on that passport. A nowhere man, ergo Paris was a good fit.

Greg: Paris did pull your multiple identities together. But I do not understand the ‘ergo’. Is there a reference here to the Beatles’ song? I am pretty sure Paris was not a ‘nowhere land’, although the dreadful idea of ‘nowhere plans for nobody’ captured the nighttime doubts and fears accurately enough.

Rafael: There were a lot of ‘nowhere people’ in Paris.