Gloucester Realist Painter Jeff Weaver

America's Greatest Unknown Artist

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 09, 2024

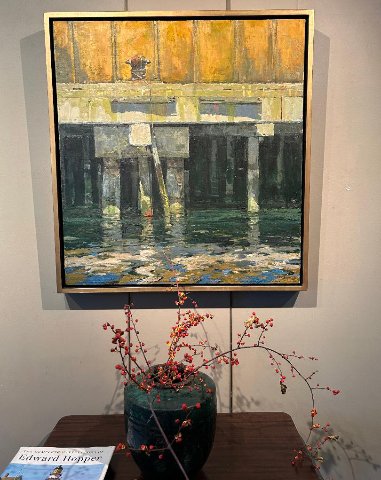

Jeff Weaver Gallery

16 Rogers Street

Gloucester, Ma. 01930

(978) 590-2979

jeffweavergallery@gmail.com

jeffweaverfineart.com

While Jeff Weaver is among America’s elite realist painters his work is not widely known beyond Gloucester. During Gloucester 400th Plus an exhibition, This Unique Place: Paintings and Drawings of Jeff Weaver, was featured at the Cape Ann Museum. His remarkable work preceded the blockbuster show of Josephine and Edward Hopper who met in Gloucester during the summer of 1923.

It was a natural segue from Weaver to Hopper but my review for Arts Fuse proved to be its only critical attention. There was a brief notice in the Gloucester Daily Times. I opted to review the work before I met the artist.

Hopper stated that he was attracted to light reflecting off the sides of buildings. That summer he was introduced to watercolor by Josephine Nivison who he soon married. One could see that progress in the show with many works borrowed from the Whitney Museum.

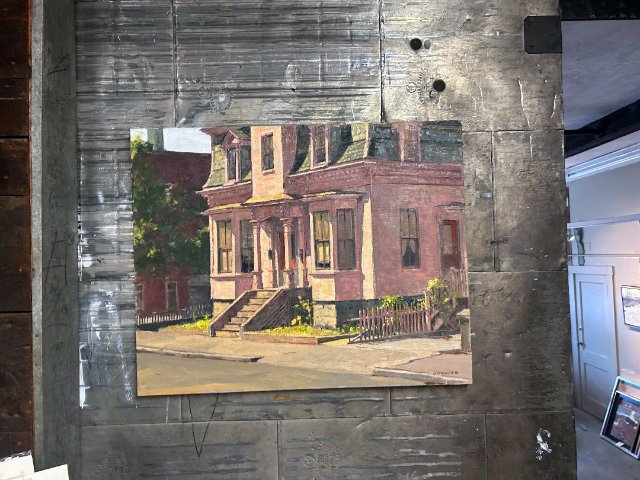

The Hoppers didn’t have a car so the buildings they rendered form a tight walking tour of downtown Gloucester. There’s a view of the harbor, a beach scene and boats but, like Weaver, Hopper was primarily interested in the indigenous architecture of The Fort and Portuguese Hill. They are plain, vernacular dwellings with a singular ornate one in oil that became the cover of the catalogue and a logo for the Hopper show.

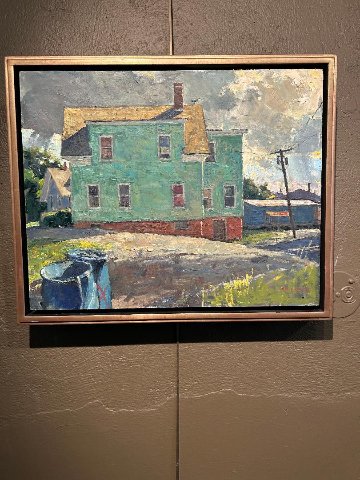

Comparing them I concluded that Hopper was the better artist with Weaver, hands down, the better painter. Few is any can match his skill at rendering the texture of flaking paint on the side of a building.

One such work, a large, minimalist rendering of a blue wall in brilliant light was the star of the CAM show. “I could have sold it twenty times over” he told me in a warmly chatty manner during a studio visit.

“Why don’t you paint ten more” I asked. The surprising answer is that so far he has painted three. The prize piece sold for $20,000 a benchmark for the artist. In an average year, he sells some 35 pieces out of the studio/gallery. Because he doesn’t have a gallery there isn’t the usual markup and 50% split. It allows for absurdly modest prices given the quality of the work.

Who are the Weavers I asked? Now 70, he was born in Framingham descended from an ancestor who came over on the Mayflower. They were Puritans seeking religious freedom. Later the Weavers were Quakers. Some of that rigor and austerity is felt in the work but does not explain his good-natured, down-to-earth, humor and charm. Part of the Protestant Ethic is reflected in his no nonsense daily production. As the Quakers put it, Hands to work and heart to God.

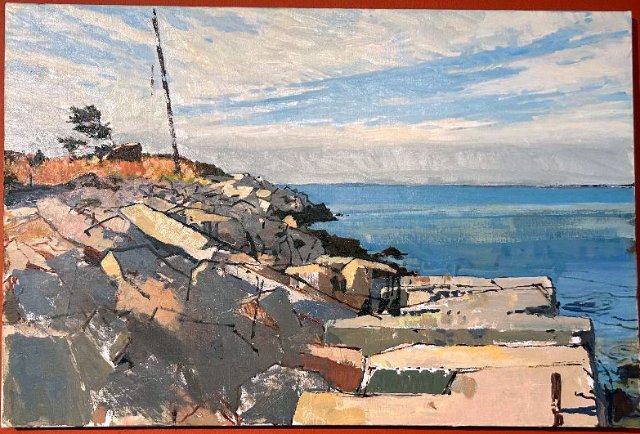

Standing in the downtown Gloucester space he stated that there is an inventory of some 60 or so paintings. The smaller ones are created en plein air and the larger ones worked up in the studio from sketches and studies, two of which were leaning against the studio wall. His primary concern is getting the composition right. One result of the CAM show is that, to his surprise, the sketches are beginning to sell.

He was able to support himself as a full time artist by 50. Since then, he has created some 500 to 600 paintings. Early on he showed with galleries but now sells exclusively from his studio.

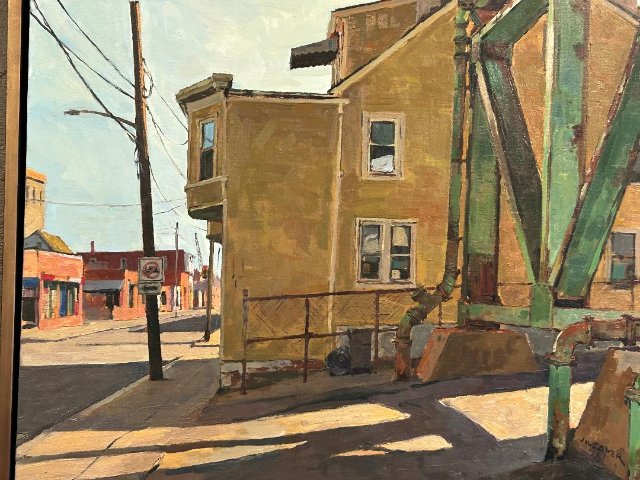

He came to Gloucester as a teenager and never left. For a year he commuted to Boston’s Museum School. At the time he was interested in sculpture and was focused on form. There is a sense of firm composition and strong structure in his work. Add to that the rich clear light of Gloucester. He explains that there are few trees that obstruct how it falls on a building.

While he studied drawing and composition there was no instruction in the techniques of representation. He recalls the Museum School as primarily conceptual. Staffed by former Boston Expressionists, the School of Fine Arts at Boston University was rooted in figuration. His friend, George Nick, a plein air painter, taught at Mass Art. “I can often spot his students,” Weaver said. Nick is known for wet-into-wet juicy paint with high chroma, and saturated color. It’s a bravura style distinct from Weaver’s meticulous layering of paint with flicks of the pallet knife for texture. A study of some surfaces evokes the pointillism of Seurat.

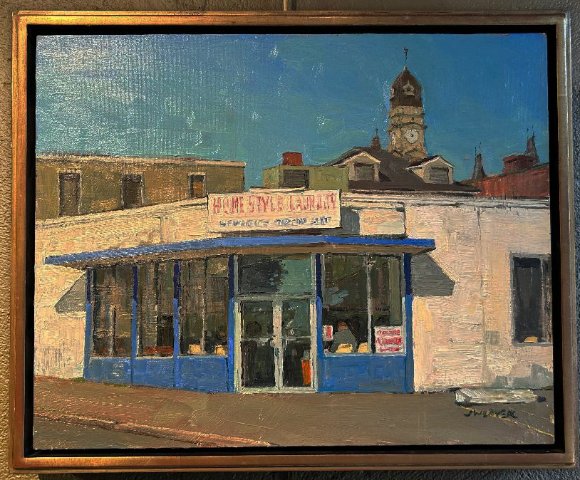

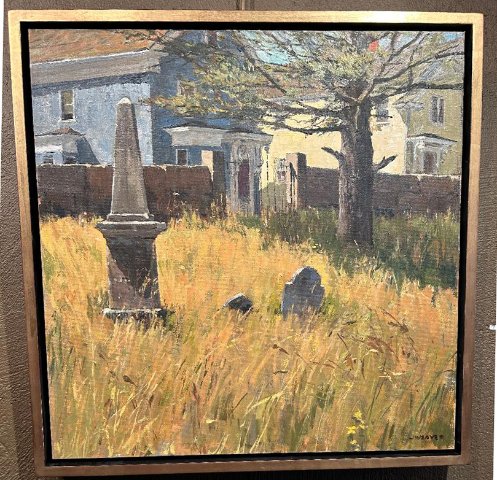

Significantly, there are few if any people in Weaver’s paintings. He has no interest in genre and narrative. It’s like Atget who photographed the streets and shops of Paris in early morning when there was no traffic. Weaver let’s his often arcane subjects speak for themselves inviting responses of viewers. We have to bring something of ourselves to relate to his work. It’s never handed to us predigested like a snapshot.

Surprisingly, he says that most people get it while the ‘new people’ ask if he has any lighthouses, seascapes, or views of the Annisquam River. It’s the Gloucester of arriviste condo dwellers with no respect for the passionate vision of old salts like Weaver. There’s an abundance of that genre to be had in Rockport. The power of Weaver’s vision is about what it’s not.

Weaver is out painting year round capturing a variety of seasons. Gloucester by the sea can be a stormy and moody place. There are winter scenes with snow and dim light that convey the gloom. It is also the time of year when, free of tourists, Gloucester is most Gloucester. It’s when artists and writers hunker down and get work done.

Part of Weaver’s lack of critical attention comes from his work erroneously being linked to the kitsch and sentimentality of the Rockport/ Gloucester School.

I asked what’s different? “I don’t paint post cards” he explained. “What’s the point of painting something that you already know like Motif Number One (in Rockport). It just triggers an automatic response. I want to show you the beauty of something you probably haven’t noticed.”

“If you painted dogs” I suggested, “Your subjects would all be mongrels.”

The work is generally about the road less taken. Punching in each day this proletarian artist, utterly devoid of pretense, works off the beaten track. He depicts his own vision of Gloucester; one that locals delight in recognizing. They are sites and structures that tourists never pay attention to as they drive by on the way to Good Harbor Beach. Weaver provides a manner of looking at Gloucester that’s been hiding in plain sight.

Not only are his paintings often less than pretty as a picture, some might qualify as grotesque. I was riveted by a large, generic dwelling, rendered in shadow hovering under what proves to be the Tobin Bridge in Chelsea. While a monstrosity I could readily imagine living with it. He has also painted the industrial waterfront of East Boston.

He related starting to paint a large waterfront shed. The next day it was half demolished and he was told not to trespass on the construction site. “It was Thanksgiving weekend with nobody around and I was able to finish the painting.” The East Boston site is now a housing development.

When I bought a three-decker on Webster Street of Jeffrey’s Point it was cheap enough to put on a credit card. With renovation it cost $85,000 which tripled when Astrid and I moved to the Berkshires.

If we had handicapped parking back then, like a ridiculous number of our neighbors, we would likely still live there. It was brutal particularly after snow storms. There were resultant slashed tires and keyed cars.

A neighbor marked his spot with a barrel in the middle of the summer. “Funny” I said, “I don’t see any sign of snow.” The growling response was “Fuggeddahbouit.”

Mostly, I miss the many wonderful restaurants like Santarpio’s, the best pizza joint in Boston.

Jeff lit up, went to the storage racks and came back with a work on paper. It depicts Santarpio’s under the elevated highway. The image evokes so many rich and tasty memories.

The greatest threat to his work is gentrification. Decaying domestic and industrial sites, his bread and butter, are being demolished and replaced by condos. Gloucester’s waterfront fisherman’s neighborhood, The Fort, may look the same but the interiors have been gutted and homes flipped. One-percenters have driven out working families. A sprawling, upscale hotel, Beauport, hogs the view and beach on what might have been a community space. Like Hopper, Weaver depicts the historic Fort but takes a pass on the hotel.

Weaver has been around long enough to observe dramatic change when Gloucester died as a working port. As a youngster, he scraped the hulls of wooden trawlers and went to sea with the Italian fishermen. The fleet was deliberately sunk and torched for insurance money when it became obsolete. To compete with factory ships depleting the Grand Banks, during the Reagan era, captains were encouraged to invest in larger metal-hulled vessels. Most investors, often partnered families, went bankrupt. The burden fell on those who could least afford it.

He told of knowing every inch of the picturesque trawlers, loving their shapes and forms. There is no such enticement to metal hulls.

Early on, he developed a widely employed skill as a sign painter. That entailed inscribing names and numbers on many vessels. He was also a much in demand muralist for restaurants and commercial buildings. There are ten of them in Gloucester. These works, like WPA murals, may be seen from Maine to Florida. With humor, he described a commission to paint views of the New Orleans French Quarter which he has never visited.

I was amused to learn that one of those murals decorates Causeway our favorite Gloucester restaurant. Good grief, he even confesses to including Motif Number One in a restaurant project.

He was fifty or so when he made enough from his paintings to ditch commercial work. He even changed his phone number. Since then he has earned a steady income as a full-time artist. He could have bought his studio for cheap but didn’t want to become a landlord. Now the building in a choice location is worth upside of a million dollars.

Also his subject matter, those mongrel indigenous structures, is threatened. He’s not interested in the mansions of gated Eastern Point, or quaint Annisquam, Lanesville, Bass Rocks, or good grief, touristy Rockport.

Like Bierstadt he is dedicated to painting “The Last of the Buffalo.” His work is a visual essay on the beauty of the generic and quotidian. It’s a study of non architecture created by carpenters and builders with no penchant for ornament and design. Weaver allows us to find the beauty of the unseen. To view his work is to revel in invention and discovery.

He is documenting the indigenous beauty of what was. That led to the elephant in the room.

With a laugh he preempted my thought. “You want me to paint the condos.”

“Yes” I responded. “But in a Weaver way with irony and social justice.”

Significantly, he didn’t dismiss the notion. No doubt a one-percenter would snatch it up for mega-bucks.