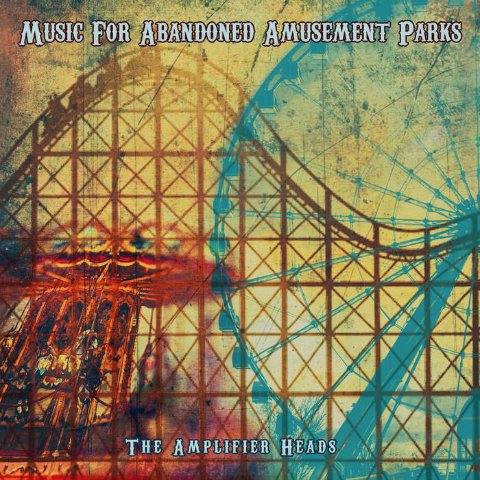

Music for Abandoned Amusement Parks

Uncanny Masterpiece by East Boston's Sal Baglio

By: Frank Conte - Jan 01, 2022

Since he began writing songs at the age of 12 in his Paris Street flat in East Boston, Sal Baglio channeled the many places of wonder around him, whether they be the long-gone Central Music shop, where he awaited the latest record release from his musical heroes; or the Sacred Heart school playground where he chased girls around; or Suffolk Downs known to him for the Beatles of 1966 not the thoroughbreds. And, then there was the most magical of places, the amusement park. In his time there were a few — Paragon Park, Pleasure Island and the closest with a Blue Line ride, Revere Beach Boulevard if one could call it that.

These veritable little discounted Disneys are the subject of Baglio’s recent work: Music for Abandoned Amusement Parks. It is—to borrow a phrase from Pete Townsend — an uncanny masterpiece. * Indeed, it is that good, so good other artists are sure to envy it. Crafted in uncertain times, MFAAP takes us away from the doldrums of the pandemic with a musical journey into a lost world. But the delightful mysteriousness commands your attention, replay upon replay.

Great works impose themselves upon you. MFAAP is a concept album that must heard as intended by the artist: 16 pieces of varied but short length. Hear in order from start to finish. It’s not to be heard in bits and pieces in shuffle mode. No, the aesthetic unity of all the pieces draws you in as a story unfolds. Style, technique, balance, harmony and narrative are found here.

Above all, MFAAP is infused with meaning and a great sense of place delivered with the right touch. It is a pity that such music cannot break through universally.

It is a chapel with the soul of a cathedral. Short instrumentals hover over like the soundtrack of a David Lynch film, moving you along and introducing the next scene. Memories are refreshed and so are themes of joy and sadness. Invitations are announced. The opening song, “Funhouse Mirrors” commands: “Arise, arise today’s the day the carnival arrives/ like the perfect birthday gift unwrapped before our eyes/ hurry, hurry let’s all scurry/ for our favorite rides.” An occasional mellotron punctuates the story, often complementing the harmonics of a perfectly strummed guitar. Carnival sound effects show up at the right time. When necessary, electric guitars blare, then soothe at just the right moments before exploding in cacophony as the story demands. Homages to Baglio’s many influences emerge tactfully and tastefully (as in “Song for an Abandoned Amusement Park” which could well have been written by Lennon and McCartney.) There’s also a swirl of Nashville there (“Candy Apple Girl”) and a bit of New Wave (infused in “Black Mascara”) and a touch of classical guitar (“Addio” and “Ghosts of the Promenade.”)

This is more than just music. It’s storytelling of the kind that an older and wiser Baglio has refined as a solo artist now that he’s retired The Stompers, his legendary Boston rock band. In the spotlight alone, he does not fail to shine.

Clearly this is not Freddy Cannon’s “Palisades Park” (a Baglio favorite). And, it certainly is not a joy ride all the way through and good times lead to worrisome ones. In Baglio’s reading, amusement parks were all magic domains of first dates, first kisses and first loves. The first half recounts these appropriate passions and all the fun: wild roller coasters, funhouse mirrors, houses of horror, arcades, candy apples and cotton candy. They hold a special place that animates Baglio’s creative spirit, “a pocket full of memories… that are locked there in a world apart from everything’s that’s seen.”

But amusements parks die and memories drift. Others have stories to tell, Baglio reminds us: the tragic characters that make joy rides run: the carnys whose stories are rarely front and center. In Baglio’s telling, they are the ones who “try to fit in but just get stuck.” No quiet lives of desperation have ever been captured so beautifully.

“Song for an Abandoned Amusement Park” the most Beatle-esque tune with its great chorus — shifts the tone of the narrative, an almost supernatural pivot. Slowly moving toward despair, the last carney ghost dances on a wooden leg on the ground where the missing teeth of barkers are buried and where the matterhorn ride is torn down “just before the plague.” Now, “The boys and girls all on the tilt-a-whirl are ghosts/ At the funhouse mirrors/ their shattered slivered hosts.” The joy rides come to a close.

The album’s hardest rocker is “Freaks,” an edgy, defiant cry on behalf of the of the alienated carny. “I never cared for people/They’re brutal and unreal/ I like to stay alone/In my trailer by the Ferris wheel/I work as a carny/With a girl name of peg/She likes to carve her name into my wooden leg.” Delivered with a great guitar energy worthy of Adrian Belew, “Freaks” unveils our carny’s impeding fate as he mocks death marching quickly toward it but apparently just not yet. “When I die don’t bury me/Scatter my ashes neath the dogwood tree/Sing a song and dance around/ And send me off to Gibson town.”

Baglio leads us to “Music for Abandoned Amusement Music Parks No. 2” which lends a whistling-beyond-the-graveyard feel — setting up the album’s climatic piece. Here we find a master at work.

The artist takes “Freaks” and strips it to its essence revealing its loneliness before the darkness comes. Shorn of its edginess and fabulous noise, “Freaks” is transformed into “Freak,” an elegy for the carney whose last midnight dance has long passed. On death’s door, the carney is stoic, devoid of any future hope. Baglio’s device here (in one of the album’s longer pieces) is most sublime keeping it all minimal and avoiding the temptation of greater instrumentation that is better used later. His singing of the last altered lines is heartbreaking. “When I die don’t bury me/Drag my ass to that dogwood tree/Salute me with a beer and song/Leave my bones here in Gibson town.” Evocative elegies do not come better than “Freak.” The tears are all too real.

In the end, it is not only souls who are abandoned but the entire juggernaut. The finale —in the vein of the looping techniques found in the post-performance work of the Beatles (think Revolution 9) — conveys the collapse of the physical world leaving only the ghosts of kids and carneys in the midst. As a coda (and ironically the work’s longest piece) the instrumental “Music for Abandoned Amusement Parks No. 3″ swells early with a symphonic quality before giving way to tin drums and a saturnalia of guitar feedback and sound engineering that carry our ghostly voices back and forth. Tranquility comes at the end, found in the last notes of a lonesome carousel. And so, the apocalypse arrives with its beauty, terror and sheer humanity in a lost world full of distortion that can be beautiful and frightening at the same time. * *

The term masterpiece is thrown around too recklessly in contemporary culture. It would take some undertaking of a godly pursuit to think of Music for Abandoned Amusement Parks as anything other than a masterpiece.

Music for Abandoned Amusement Parks is available on Bandcamp and Apple Music.

*Upon hearing King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King in 1969, an awestruck Pete Townsend of The Who —in a flash of whimsy— called the album an “uncanny masterpiece.” Indeed, it remains a classic. For more see https://eastboston.com/?p=4792

**Paraphrasing a passage from Ralph L. Gleason’s liner notes to Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew. http://albumlinernotes.com/Bitches_Brew.html

Reposted courtesy of East Boston.com